Art of the Commons:

Envisioning Real Utopias in Postindustrial Detroit

Vince Carducci

Images courtesy of the artist

For the better part of four decades, the city of Detroit has been an icon of urban disinvestment. The city has been steadily losing population from its mid-1950s peak of 1.85 million to a little over 700,000 today, according to the most recent figures from the US Census. Along with the population loss has come the widespread abandonment of the city’s physical plant with many neighborhoods and industrial areas reverting nearly to open field. As historian Thomas Sugrue most notably has shown, the evacuation actually began with the suburban expansion after the Second World War but became more apparent in the wake of the 1967 civil disturbances, which were a reflection of growing economic and racial inequality in the city and its environs. 1Thomas Sugrue, The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1996). See also …

In recent years, the devastation has taken on a romantic patina in the form of the photographic genre known as “ruins porn.” Featured most prominently in books such as Detroit Disassembled by Andrew Moore and The Ruins of Detroit by Yves Marchand and Romain Meffre, the form is marked by glamour shots of the city’s deliquescing architecture, often printed in large format with a glossy sheen.2Andrew Moore, Detroit Disassembled (Bologna, IT: Damiani Editore; Akron, OH: Akron Art Museum, 2011) and Yves Marchand and Romain Meffre, The Ruins … Yet, while the erstwhile Motor City’s identity as a steam punk avatar of modernity gone awry possesses scopophilic allure, there is another, more fertile tendency that has emerged, which I call the “art of the commons.”

The art of commons trespasses the boundaries of conventional property relations of modern capitalism, existing in an indeterminate zone between public and private as customarily understood. Historically, the notion refers back to the medieval commons, land left open for grazing, farming, and other uses by anyone without requiring individual ownership (the term “commoner,” i.e., one without hereditary title, comes from it). A more contemporary interpretation derives from the idea of the commons as put forth by Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri in their book Empire as: “the incarnation, the production, and the liberation of the multitude,” the collective freeing of land and labor from capitalist economic and social relations.3Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Empire (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000). It is a concept Hardt and Negri develop in subsequent works, and one that is being explored on a number of fronts in the face of the seemingly ongoing crises of the global capitalist system.4Hardt and Negri, Multitude: War and Democracy in the Age of Empire (New York: Penguin Books, 2004) and Hardt and Negri, Commonwealth (Cambridge, MA: … The commons as envisioned by Hardt and Negri is a collective social practice that recognizes the connectedness of things behind the abstractions that seek to divide them up into ownable pieces whether of physical nature or of the more ephemeral.5Hardt and Negri, Commonwealth, 120-125. The provenance of real estate ownership, i.e., deeds, mortgage liens, litigations, etc., is legally termed a …

The commons has emerged in Detroit where conventional property relations appear to have withered away, where large-scale abandonment of the urban core has literally deconstructed the conventional distinctions between the private and public spheres and revealed, paraphrasing the famous Situationist International aphorism, “the beach beneath the streets.”6The original aphorism comes from the May 1968 Paris student uprisings, “Sous les paves, la plage!" (Under the pavement, the beach!). My usage comes …

The reclamation of the commons can be seen in grassroots activities such as the urban farming movement where in many cases it is unclear where title resides to the land being cultivated and residents simply work the plots and harvest the results.

The art of the commons first emerged in desolate zones of the city where the distinctions of conventional property relations had been effectively erased, in places where the abandoned landscape offered opportunities for creative agency to flourish by force of sheer will. The most notable early example is Tyree Guyton’s Heidelberg Project, begun in 1986 on the street on Detroit’s East Side where the artist grew up, which at the time had been virtually annihilated by not-so-benign neglect. Guyton’s project, which spreads over more than two city blocks, is not strictly speaking private as it is available for all to freely experience, resisting assimilation into the private domain of commercial galleries and collectors. In addition, The Heidelberg Project was initially undertaken outside the official channels of public art, which vet the creative expressions that are allowed entry to the public sphere. Indeed, the City of Detroit government has tried twice to demolish the project, citing its interference with urban development plans and a rash of neighborhood complaints as part of its action, with Guyton simply rebuilding it anew each time.

Appropriating vacant houses and empty lots and using castoffs retrieved from around the neighborhood, the artist created a sprawling outdoor installation that drew attention to and commented on the failure of the modern urban order. Guyton festooned one structure with salvaged doll parts. Another was covered with multicolored polka dots that spilled out onto the street. Discarded doors and car parts were painted and fashioned into freestanding sculptures and placed in different locations around the neighborhood. Most chilling, a tree’s barren limbs were trimmed with shoes suspended by their knotted laces, to the unsuspecting eye an imitation of the practical joke of tossing footwear out of their owners’ reach but in fact referring to the memories of the artist’s grandfather, a descendant of slaves, who told tales of the lynching trees from his rural youth in the South where all that passersby could see were the soles of the victims’ shoes dangling overhead.

Another, more recent example of the art of the commons is Scott Hocking, who for more than a decade has drifted through Detroit’s nether parts, working in the manner of the Situationist dérive. In the course of walkabouts among the city’s industrial ruins and other neglected spaces, Hocking creates installations and other interventions, and he documents them photographically along with other aspects of Detroit’s postindustrial psychogeography. Often the result of weeks if not months of solitary labor, these projects are undertaken with full knowledge of the likelihood of their eventual destruction either by human intervention or exposure to the elements.

The Power House, 2009-present.

Ziggurat (2007-2008) documents a sculptural installation Hocking built in Fisher Body Plant 21, a building that had been abandoned for the more than 20 years. The installation was constructed over several months between winter 2007 and summer 2008. It consisted of some 6200 wooden flooring blocks retrieved from around the empty building fashioned into a stepped pyramid, since destroyed and returned to the pile of rubble from which it came.

The Garden of the Gods (2009-2011) pushes the inevitability of entropy even further. It is sited in the old Packard Plant, a 3.5 million square foot facility, nearly half a mile in length and believed to be the largest abandoned industrial site in the United States, which has been derelict for decades. On a section of collapsed roof in the building designed by Detroit’s premier architect Albert Kahn, Hocking placed a series of old wooden TV consoles he found on a lower floor atop structural columns that had remained upright. Over a period of months, some of the columns toppled and more of the roof collapsed, events also documented photographically. Named after a sedimentary rock formation in southern Illinois, Garden of the Gods isn’t a ritual of mourning but an acknowledgment of natural processes that have occurred throughout history.

Envisioning Real Utopias in Postindustrial Detroit

The “unconcealing” of the commons has provided an opportunity for new aesthetic practices to emerge that can be looked at from a sociological perspective using Eric Olin Wright‘s model of social change, the “real utopia.”7Wright, Eric Olin, Envisioning Real Utopias (London: Verso, 2010). As opposed to traditional utopias, which are ideal communities of admittedly unattainable perfection, real utopias, according to Wright, combine “principles and rationales for different emancipatory visions with the analysis of pragmatic problems of institutional design.” Real utopias are ways of envisioning conditions of social and political justice that are at once desirable, viable, and achievable. In keeping with this, real utopias are thus models of emancipatory social transformation, alternative ways of providing for human wellbeing. Elements of the aesthetic community of Detroit operate as such real utopias, negotiating within what Wright terms the “niches, spaces, and margins of capitalist society,” in what I have been calling the commons.

One of the notable examples of this in Detroit is the work that has been done over the last five or so years by Design 99, the collaboration of artist Mitch Cope and architect Gina Reichert. Started as a design consulting studio and retail space, Design 99 has evolved into broad-based conduit for exploring models of contemporary art and architectural practice and community engagement. In 2008, Design 99 acquired a foreclosed and abandoned residential structure on Detroit’s northeast side for $1800, which they began to use as a test site for sustainable design and social practice. Project plans called for the structure to be rehabilitated using recycled materials and be completely energy self-sufficient, combining wind and solar technologies for all of its power needs. The project, known as the Power House (for its aspirations of both self-sufficiency in existing off the utility grid and self-determination with respect to personal and community empowerment), soon attracted attention and support from local residents. Kids started coming by to help paint and plant, and the daily proceedings became a source of conversation for adults.

In 2009, Cope and Reichert formed Power House Productions, a nonprofit organization to extend their work into the nearby neighborhood in a more comprehensive and coordinated way. Founded in the wake of the 2008 financial meltdown, the organization started as a defensive mechanism against the increase in crime and vandalism that plagued the already blighted neighborhood. Power House Productions facilitated the acquisition of eight more houses and three empty lots in the neighborhood. Five of those properties are currently undergoing rehabilitation for use as primary residences. There are community gardens, neighborhood clean-ups, and neighborhood watch programs in effect. The San Francisco-based magazine Juxtapoz also partnered with Power House Productions on a multiple-location art-installation project. Future plans call for a neighborhood bike shop (Detroit has become a major bike city) and a series of artists’ residencies and workshops.

Related projects have now followed. The University of Michigan School of Architecture sponsored five graduate fellowships in 2009-2010 to conduct design research, purchasing houses in the neighborhood to allow them to work at full scale. Chicago-based artists Sarah Wagner and Jon Brumit moved in and formed the project DFLUX Research Studio to explore the possibilities of emergent creative cottage industries, famously purchasing a house for $100 in which to conduct their activities. The artist Graem Whyte (himself co-director of another nearby artists’ enterprise Popps Packing) is working on the Squash House project (2012-present), a site-specific interaction space focusing on play and gardening as the primary mechanisms for community building. Like the Power House, it will be energy self-sufficient and use recycled materials wherever possible.

Power House Productions recently received a $250,000 grant from ArtPlace to convert three vacant houses in the neighborhood into sites for art and community engagement. The piece of the overall project that seems to have the most immediate effect is Skate House, which is part of the Ride It Sculpture Park (2012-present). When completed, Skate House will feature an indoor skateboarding track and residence for visiting skateboarders and artists.

Ride It Sculpture Park is situated on four adjacent vacant commercial lots at the terminus of the Davison Freeway, the nation’s first below-grade limited access urban highway, opened in 1942 to service nearby defense manufacturers during WWII when Detroit was known as the “Arsenal of Democracy.” The project is a collaboration of skateboard enthusiasts and artists in the area as well as nationally. Design 99 and artist Brumit are the principal park design team and video artists. Other collaborators include skateboard accessories providers Emerica and Independent Truck Company, media outlets Thrasher, Slap, and Juxtapoz, and a crew of volunteers. A 2012 fundraiser auction of artist’s skateboard decks, including one designed by international artist Matthew Barney, netted more than $25,000 for the project. A Crowdrise campaign exceeded its goal. Ride It Sculpture Park recently received additional support in the form of a $30,000 Tony Hawk Foundation grant, and Design 99 principals Reichert and Cope have also been named 2013 Creative Capital project grantees and received the $100,000 ArtPrize Juried Award for 2012.

Although not officially completed, the first phase of Ride It Sculpture Park is substantially in place and functional. The concrete construction features several ramparts, quarter and half pipes, spines, and banks. There’s a built-in barbeque pit off to one side. The facility is already being used by skateboarders and BMX riders, many of whom have come from far beyond the neighborhood, having heard of the park through skateboarding community social networking on Facebook and Twitter. The national organization Boards for Bros has given away skateboards to kids who couldn’t afford to buy their own, and more seasoned riders have helped neophytes get on board so to speak.

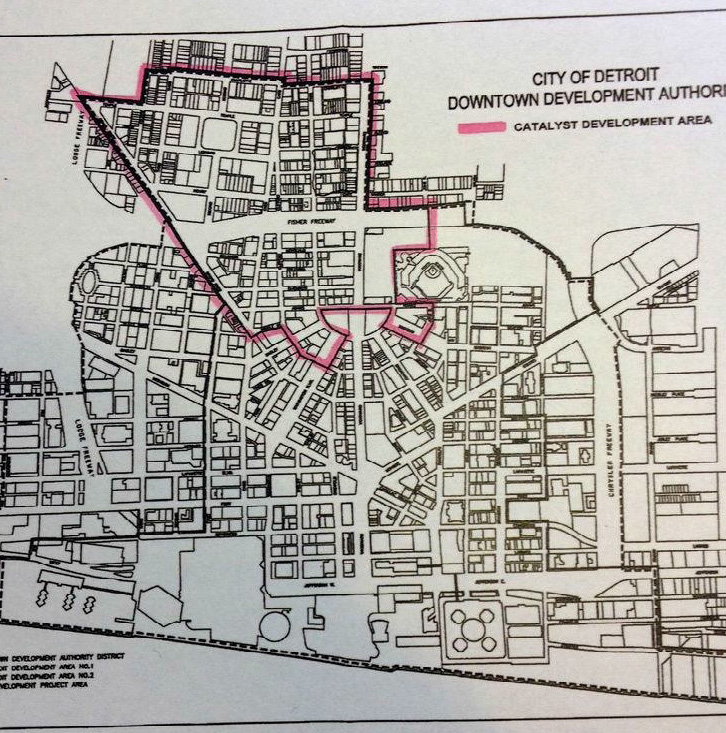

How long projects like this will continue to be possible is questionable. Recently a small group of investors in nearby Macomb County, a primarily working class suburban region and Tea Party stronghold northeast of the city, purchased every available tax-foreclosed property (a total of 645 parcels, including 403 residential) for a lump sum of $4.7 million. The inventory in Detroit exceeds that by many multiples. (By one estimate the total hit for tax-foreclosed properties in Detroit would come to more than a quarter of a billion dollars.) But news outlets such as NPR have reported stories of foreign investors from places like London and Dubai buying up large lots of Detroit real estate in speculation. And most recently local investor John Hantz negotiated with the City of Detroit to buy 1500 lots for the Hantz Woodlands urban tree farm at a bargain-basement price of $520,000, under $350 a parcel. The recent naming by Michigan Governor Rick Snyder of an Emergency Financial Manager for the City of Detroit with virtually unlimited authority to reconfigure the city politically, economically, and physically raises additional uncertainty.

Even so, there is an abundance of the commons yet at hand in Detroit. And in the short term at least, these zones are still available for transformation in the manner discussed above. As Wright notes, real utopias have the best potential to emerge in situations where conventional structures are simply not available. They’re forms of social bricolage (in contemporary parlance DIY), which hold the promise of modeling a new order. The art of the commons augurs such a hope.

Images from Ride It Sculpture Park (2012-present) and The Heidelberg Project. (courtesy of the artist)

References