LEARNING FROM DETROIT: THE POETICS OF RUINED SPACE

Barrett Watten

Driving outside of myself. Into the social space of Detroit. A network of concrete radiating outward from a collapsed center. This is the urban landscape Henry Ford built on the basis of mobile transportation, now an immobile and unfixable infrastructure. Once locked into place, forms of desire are abandoned and crumble to dust: urbanized wildlife traverses the spaces between them…. Driving the Lodge Freeway at night, the intermittent stream of traffic. Frontal flare-ups of headlights and departing streaks of taillights. Who are these drivers, from what grid-locked suburb to what desiring end? Restaurants, bars, casinos, and entertainment. Aberrant drunk on wrong side of the road passes drug-related police event in progress. Tanker truck explodes, to become the defining moment of the news cycle.

—Barrett Watten,”Double Negative”((From The Grand Piano: An Experiment in Collective Autobiography, San Francisco, 1975–1980, 10 vols. (Detroit: Mode A/This Press, 2006–10), 9:160–61.))

“Looking east out of one of Lee Plaza’s gaping windows towards the landmarks in Detroit’s New Center neighborhood…”

Image originally printed in Lost Detroit, 86.

Reprinted courtesy of Dan Austin and Sean Doerr/SNWEB.ORG

This passage on Detroit from Grand Piano 9 locates the critical and poetic intersection between negativity and social space I have been exploring since well before arriving in Detroit, beginning with the postmodern landscapes of the West and their ground zero in Los Angeles. Writing on California, it was the unregulated proliferation of the built environment, the landscape of frozen mobility and post-urban dissociation developed on principles first realized in Detroit, that suggested a poetics of “Non-Events” as correlative to the postmodern lifeworld. A line like “But the job of the driver is to muffle the sound of the new car turning into parts” may have seemed a self-referential, automatically generated example of “the New Sentence,” but it was also an index of the entropic decay (in the manner that sound decays in an echo chamber) of objects into parts, commodities into materials, fixities into uncertainties, and rationality into negativity as the given structure of lived experience.((Barrett Watten, from “Real Estate,” in Frame (1971–1990) (Los Angeles: Sun & Moon Press, 1997), 34.)) Moving to Detroit, for a job at Wayne State University in 1994, seemed equally a moment of decay in that sense, recalling Charlie Anderson’s hubris in John Dos Passos’s The Big Money: “You and me Bill, we’re in production, and by God I’m going to see that we don’t lose out. If they try to rook us we’ll fight, already I’ve had offers, big offers from Detroit … in five years now we’ll be in the money”—fatal words for the hero, it turns out. If at the apex of Detroit’s fortunes, production equaled consumption (with the 1949 Treaty of Detroit, the labor peace between auto unions and the Big Three brokered by Walter Reuther that was the foundation of the transition from war to postwar economies), since its boom years it has led to an economics of overproduction, outsourcing, displacement, and decline. Not progress but negativity is Detroit’s most important product, a negativity that is both sensually evident and lived—not just a theoretical (non)concept but the traumatic landscapes and fragmented communities we deal with here as a condition of everyday life. Since being in Detroit I have had numerous opportunities to access its negativity in my critical encounters with its cultural forms; given the reproductive stability of the Fordist mode of production, the results seem as relevant today as when I first wrote them in the preceding decades. If there is any geopolitical landscape that makes one skeptical of narratives of progress (outside the former Eastern Bloc, but sharing key features), it is Detroit.

“Ravaged by vandals and scrappers, the Grande’s condition belies its past…”

Image originally printed in Lost Detroit, 70.

Reprinted courtesy of Dan Austin and Sean Doerr/SNWEB.ORG

Seeking not so much progress in learning from Detroit, but to report on new perspectives and recent developments, I will take up the currently engaged debates surrounding “ruin pornography”—the uncritical and exploitative celebration of Detroit’s postindustrial landscapes. The term “ruin porn” has become the iconic genre for representing the city since the last shoe outlet closed on Woodward in 1994 or Hudson’s department store was demolished in 1998 (Detroit has no Zero Hour, a punctual moment of destruction, but a series of moments on a timeline beginning with the 1967 riots). What is clearly missing in the “ruin porn” debate is an adequate account of representation itself: negative images of Detroit are typically discussed primarily in terms of their referents, not in terms of the aesthetics of documentation, the desires enacted or displaced by visual images, the history of representations of the negative (from romanticism to the present), or finally the many theoretical and historical arguments that can be derived from these images. “Ruin porn” as a term is as reductive as the images it criticizes—with the best of intentions, but with the narrowest of aims. In order to get past the impasse of “ruin porn,” I want to fix it between two outside registers: the 1972/77 investigation into the negative terrains of the postmodern, Learning from Las Vegas, and the architectural fantasies of Michigan/New York architect Lebbeus Woods—to arrive at a present reformulation of Detroit negativity in the Dequindre Cut (2009), a 1.2-mile bike trail built on a disused rail line in an industrial area that points past the melancholy of ruins to the critical deployment of the negative in Detroit.

REPRESENTING THE NEGATIVE

A current truism circulating in the political counterculture of Detroit—from an ideological perspective that embraces small-scale participation such as urban gardening, bicycling, community activism, Facebook networking, and the $100 house as preferred weapons in the fight against Fordism—has been suspicion of the commodification of negative images of the city. This local hostility to large-format, high-definition, glossy color photographs of destroyed manufacturing and neighborhood spaces in Detroit stems in part from their predictable range of strategies—straight shots of evacuated spaces filled with detritus, often without any human presence, in coffee-table editions like Yves Marchand and Romain Meffre’s The Ruins of Detroit or Andrew Moore’s Disassembling Detroit, and in part from their outsider perspective.((Yves Marchand and Romain Meffre, The Ruins of Detroit (London: Steidl, 2010); Andrew Moore, Disassembling Detroit (Akron, Ohio: Akron Art Museum, 2010).)) To many residents, these images are predictable and clichéd, part of an endless narrative of decline cranked out by the New York Times and other media, scarcely offset by the recent trend toward more nuanced reporting in the Huffington Post, with its local bylines. Heidi Ewing and Rachel Grady’s documentary Detropia (2012) barely makes a dent in this iconography, even if they manage to create sites of human identification in a few cameo portraits. In fact, it is the question of identification that is crucial to “ruin porn” formulation—the ascription of pornography to what are after all visual clichés is proof positive of the “obscene gaze” of outsiders who “don’t get Detroit” and cannot because they have no memories of the former “Paris of the Midwest” or waiting for their mother by the clock outside Kern’s drugs on a shopping trip to Hudson’s. In this view, outsiders have no memorial register for what was lost in Detroit that subtends any image of it as negative—they can only gawk at the negative without interpretive context or background, perpetuating it in turn as a form of denial. On the other hand, a political use of documentary evidence over the past decade has raised the level of visual literacy on urbanism and Detroit and created a strong relationship between representation and activism, particularly after the opening of MOCAD (the alternative Museum of Contemporary Art, Detroit), with its use of conceptual strategies of documentation and information display, and particularly its staging of Shrinking Cities, a four-city investigation of postindustrial decline also exhibited in Manchester, U.K., Halle/Leipzig, Germany, and Iva-novo, Russia.((Philipp Oswalt, ed. Shrinking Cities, Vol. 1: International Research (Ostfildern-Ruit, Germ.: Hatje Cantz, 2006).)) As well, emerging cultural and political formations such as Occupy, the urban gardening and bicycle movements, new gallery and performance spaces, and public art initiatives such as Movement (the techno festival operating since 2000) and Dlectricity (site-specific light projections) work to offset the clichés of its monumental negativity.

Taisho Kimono Shop

Image originally printed in Hiroshima: Ground Zero, fig. 0.16.

Reprinted courtesy of the International Center for Photography

In the view of new activists in Detroit, what is misrecognized is the city’s livability, even in its present condition, rather than the forbidding, inaccessible scale of the postindustrial sublime. This emphasis on habitability rather than decline seems a heroic rejection of Detroit’s “damned demographics” (after former Mayor Coleman Young): from a peak population of 1.8 million in the 50s and 60s (the boom years of the auto industry), Detroit shrank by 50% to 900,000 residents by 2000; in the last ten years, the city lost an additional 25% of its population, 80% of them African-American, while the downtown and midtown core has gained 15,000 new residents, many of them educated and white. Given these numbers, the assertion of livability often seems a rhetoric of renewal that is a cliché in its own right; in a newsreel after the 1967 riots, former Mayor James P. Cavanagh became one of the first of a series of mayors—since 1994, Dennis Archer, Kwame Kilpatrick, and Dave Bing—to trade on boosterism as their city literally melted away under their feet. The sensory evidence and lived experience of Detroit’s manufacturing decline, residential depopulation, neighborhood deterioration, tax base erosion—in short, social negativity—is important, first of all, for undercutting the twin illusions of progress and hope, always kept alive, always around the corner, always about to be reborn, but always deferred. Undermining this false positivism—of progress and hope ad infinitum—is the first critical task of ruin photography: to offset the status quo of political denial that has kept Detroit barely together over four and half decades. Given the obviously dysfunctional gap between such totalizing narratives and local conditions, grand metanarratives and gaps in expectation, it is thus odd that “ruin porn” critics do not see the undoing of progressive metanarratives as a primary task of the negative. In John Patrick Leary’s essay “Detroitism,” arguably the best formulation of the “ruin porn” critique, we find: “much ruin photography and ruin film aestheticizes poverty without inquiring of its origins, dramatizes spaces but never seeks out the people that inhabit and transform them, and romanticizes isolated acts of resistance without acknowledging the massive political and social forces aligned against the real transformation, and not just stubborn survival, of the city”.((John Patrick Leary, “Detroitism,” Guernica: A Magazine of Art and Politics (2011); available at www.guernicamag.com/features/leary_1_15_11.)) Metanarratives of progress, origins, and transformation are defended here as opposed to forms of aesthetic denial: romantic rebellion, heatricality, and aestheticization. If the two forms of positivism seem inadvertently close, Nietzsche’s “monumental history” explains the ruins’ betrayal of hope and their critique.

To begin with, there is no one-sized-fits-all aesthetic practice of ruin photography; we must look within the formal values of the photographic image and out toward a range of visual discourses of the ruin. In putting the case for the aesthetics of denial in “ruin porn,” Leary cites an egregious example of image exploitation and narrative excess in the following:

British filmmaker Julien Temple’s documentary, Requiem for Detroit?, and his accompanying Guardian essay, “Detroit: The Last Days,” are the quintessence of the Detroit Lament. “Approaching the derelict shell of downtown Detroit,” Temple breathlessly writes, “we see full-grown trees sprouting from the tops of deserted skyscrapers. In their shadows, the glazed eyes of the street zombies slide into view, stumbling in front of the car. Our excitement at driving into what feels like a man–made hurricane Katrina is matched only by sheer disbelief that what was once the fourth-largest city in the U.S. could actually be in the process of disappearing from the face of the earth.” This is the style denounced locally as “ruin porn.” All the elements are here: the exuberant connoisseurship of dereliction; the unembarrassed rejoicing at the “excitement” of it all, hastily balanced by the liberal posturing of sympathy for a “man-made Katrina,” and most importantly, the absence of people other than those he calls, cruelly, “street zombies.” The city is a shell, and so are the people who occasionally stumble into the photographer’s viewfinder. [“Detroitism”]

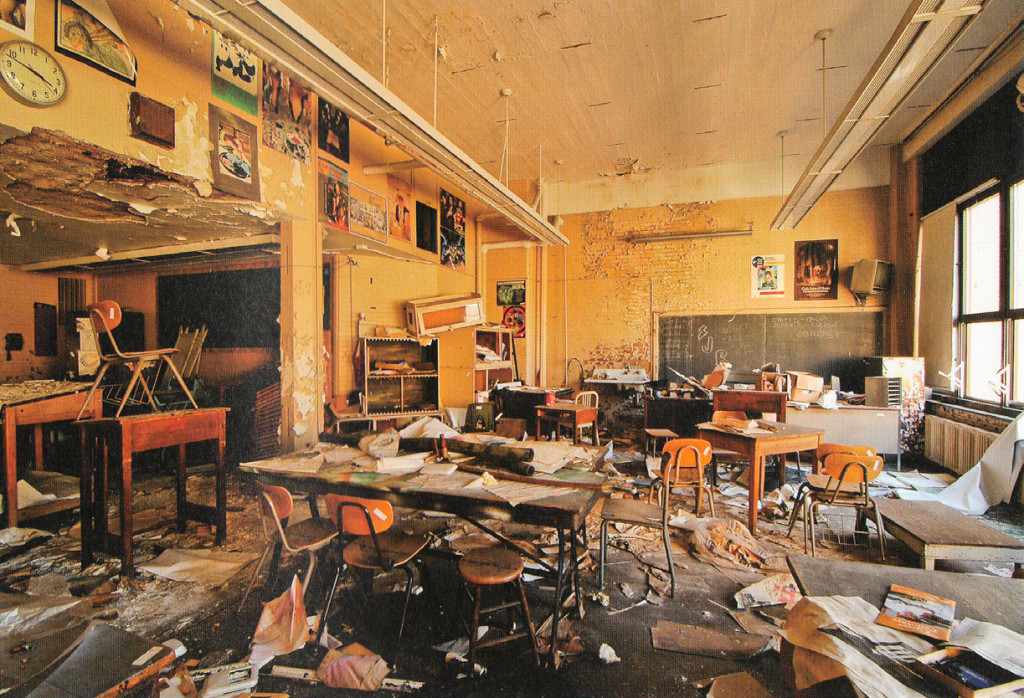

“Many of the classrooms look like class just got out. Posters and paintings still cling to the walls, and supplies still fill cabinets…”

Image originally printed in Lost Detroit, 30.

Reprinted courtesy of Dan Austin and Sean Doerr/SNWEB.ORG

Leary is right to attack this mystificatory fantasy, easily recognizable as a cultural cliché; we may say that it is in monumental bad taste, like the monuments it fetishizes. Hackneyed imagery and purple prose evidence the first reactions of the new visitor to Detroit, but this is by no means adequate for the genre of ruin photography. Canadian photographer Stan Douglas’s series Le Détroit (Art Gallery of Windsor, 1999) explored Detroit through a range of conceptual, site-specific, and installation strategies, none of which are reducible to the image. Conceptual distance, within the image, creates an iconographic allegory of part and whole, while the ensemble of images was exhibited, along with a film projection, as a critical investigation akin to Douglas’s many site-specific projects in urban and rural Vancouver. The local reaction, however, could not have been more negative: Douglas was portrayed as a moneyed outsider (Toronto finance capital) trading on lived experience for lucre; clearly, Detroit’s self-understanding had not come to terms with artistic practices such as conceptual photography or installation and site-specific art as providing mediating frameworks for interpretation. On the other hand, Dan Austin and Sean Doerr’s Lost Detroit (2010) offers narrative contexts for its investigation into a dozen iconic sites, from the Broderick Towers and Cass Tech to Michigan Central Station (after Camilo Vergara’s before-and-after sequences in American Ruins [1999]).((Dan Austin, Lost Detroit: Stories Behind the Motor City’s Majestic Ruins (Charleston, S.C.: The History Press, 2010); Camilo J. Vergara, American Ruins (New York: Monacelli, 2003).))

Dating, captioning, and historical narrative frame the final state of the ruination in a series of causes and effects: a sequence of investment opportunities, profit-making heydays, demographic changes, loss of customers or audience, real estate transfers, tax defaults, law suits and estate claims, maintenance issues, weather damage, scavenging for fixtures, and vandalism—all resulting in the current state of the building, both physically and legally. Detroit’s ruins fell into their current condition in a series of stages, not all at once: what is obnoxious about “ruin porn” is the illusion of sudden fall into destruction, so blatantly exposed and public as to be pornographic. It is the absence of proper captioning or contextualizing, either through formal or narrative means, that leaves “ruin porn” open to the illusion of a purely aesthetic exploitation in denial of lived experience.

“The soaring hall once echoed with the sounds of hellos and goodbyes and panting, screeching locomotives…”

Image originally printed in Lost Detroit, 117.

Reprinted courtesy of Dan Austin and Sean Doerr/SNWEB.ORG

NEGATIVITY AS CULTURAL WORK

To better understand the full range of meanings and affects in Detroit ruin photography, as well as its critical potential, we can position it at the intersection of three discourses: romantic sublime, modern documentary, and postmodern critique. Fascination with ruins was, of course, a hallmark of romanticism—easily accessible in the work of Caspar David Friedrich; for Hegel, the romantic ruin was the highest aesthetic form, in that it demanded completion in spirit as an entailment of its materiality. It would be easy to transfer this value to Detroit ruin photography, seeing the form of the ruined building as not only a specter of the past but a promise of the future, endlessly deferred: this is a persistent ideology in Detroit. Architect Lebbeus Woods, whom I discuss below, criticizes the sublime affect of ruins as historically complemented by the false holism of National Socialism’s moment of renewal, even though in Detroit, the metaphor of “rising from the ashes” (the city’s Latin motto; the Renaissance Center) keeps its everyday meaning without any hint of fascism. Modernism, particularly the objectivist and documentarist movements of the 20s and 30s, inverted Hegel’s horizon of spirit in the romantic ruin, locating it in the present of the material image. The historical completion of the modernist image turned out to be destruction rather than spirit, evidenced in the genres of war and ruin photography, which maintained a high degree of aesthetic value but also served a practical function in accessing war damage. At Stunde Null, the “punctual moment” of destruction at the end of World War II, aesthetic and historical uses of the ruined building combined in a photographic genre that anticipated the postwar boom in construction; to these we may add the iconography of nuclear destruction at the original Ground Zero.((Rolf Italiaander et al., eds., Berlins Stunde Null: Ein Bild/Text-Band (Dusseldorf: Droste Verlag, 1979); Erin Barnett and Philomena Mariani, eds., Hiroshima: Ground Zero 1945 (New York: International Center for Photography, 2011).)) An undercurrent of destruction in the postmodern unites the Las Vegas strip, with its leveling of taste and proliferation of styles, with the atomic tests undertaken through the 50s not far from there.The destruction visible in Detroit ruin photography may be positioned in a much larger postwar historical series, in which the threat of atomic destruction of the urban core led to evacuation to the suburbs. Rather than merely celebrating the negative, Detroit ruin photography may be said to stabilize it and turn it to use. We may elucidate this positive advantage of Detroit negativity by comparing to the negative embrace of postmodern positivity in Learning from Las Vegas.((Robert Venturi, et al., Learning from Las Vegas (1972; rev. ed., Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1977).))

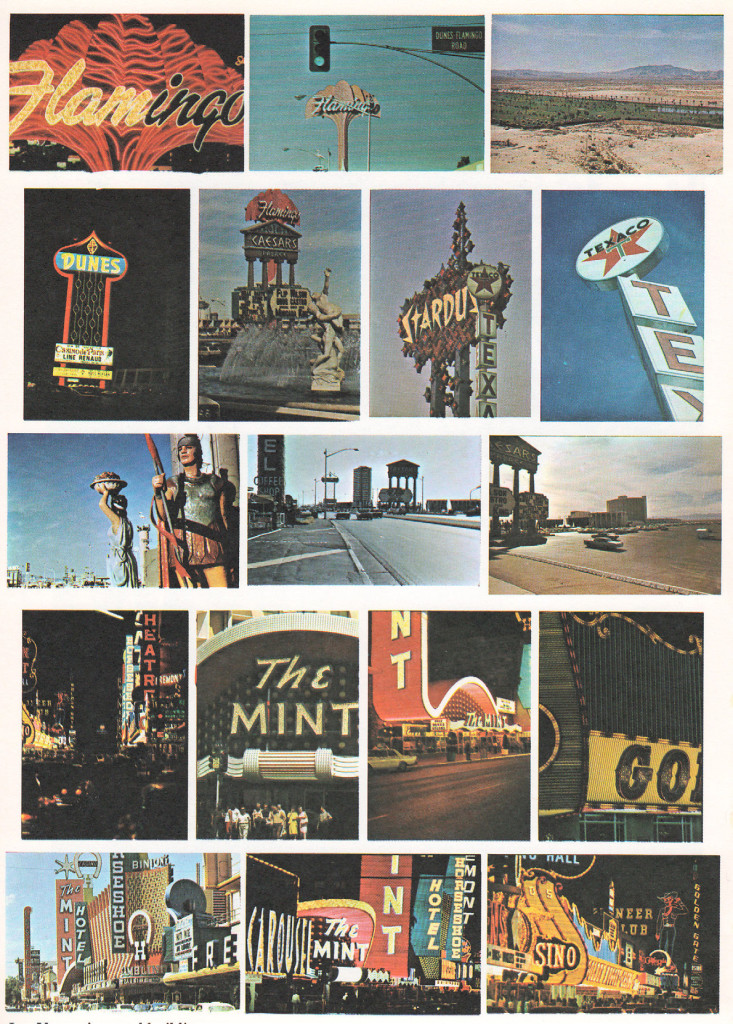

Las Vegas signs and buildings

Images orginally pritned in Learning from Las Vegas, 62.

Reprinted courtesy of MIT Press

What Las Vegas taught modern architecture was to embrace the evacuated surfaces, sprawl, and signage of the hotels, parking lots, and the Strip for their symbolic value as a material to be mined for its constructive potential as well as a critique of modernist monumentality. The aesthetic detail that to a modernist seems functionless, discordant, and unpleasant becomes a radical particularity that “questions how we look at things” (3), yielding its critical potential. For Detroit ruin photograph, “withholding judgment” of the building’s evacuated meaning “may be used as a tool to make later judgment more sensitive” (ibid.)—the question is how. For both Las Vegas and Detroit, the en-closed spaces and autonomous forms of modernism are rejected—through overbuilding or evacuation. Genres of architecture either proliferate beyond recognition or regress to dysfunctional examples—while Las Vegas destroys the values that distinguish between genres, Detroit evidences the unique failure of multiple genres. Four concepts unite these seemingly disparate phenomena: 1) a foregrounding of the symbolic, rather than functional, dimension of building—for Las Vegas, the positivity of ornament and signage, for Detroit, the negativity of the ruin’s undoing of form and function and resulting gaps in the built environment; 2) an acceptance of entropy, devolution, chaos, and the unformed as architectural possibilities; 3) a privileging of materials and surfaces rather than the total form of the building or its relation to a landscape; and 4) an attention to the forces of destruction at the core of modernity. In Detroit ruin photography, we can identify these common elements of postmodern critique (which must be seen as historical in terms of Detroit’s difference from Las Vegas): 1) its ruins are symbols that release critical consciousness that can be put to constructive ends; 2) its evacuated urban core demands that logics of autonomous form, of center and periphery, be abandoned for new ways of imagining a city; 3) its focus on material detritus in ruin photography refuse the subordination of material to form and demand a critique of sustainability that anticipates both the uses and disuses of a building or urban infrastructure; and 4) its acknowledgment of the destructive scale of capitalist social relations provides some conceptual tools to survive it. Gaps, formlessness, materiality, and destruction are the elements of architectural vocabulary to be learned from Detroit.

In conclusion, I will briefly point to two tendencies in urban architecture that sup-port the criticality of Detroit’s lessons in destruction. The first is the work of experimental architect Lebbeus Woods, a Michigan native living in New York who has produced a remarkable corpus of unbuildable architectural fantasies.((Lebbeus Woods, Tracy Myers, and Karsten Harries, Lebbeus Woods: Experimental Architecture (Pittsburgh: Carnegie Museum of Art, 2004), cited as LW; and Woods, Radical Reconstruction (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1997), cited as RR.)) In Woods’s imagined architecture, destruction and detritus are integrated into the form of building itself; no building can survive its own tendency toward entropy, and this is symbolically acknowledged through its extrinsic form. In the late 80s, Woods was influenced by the favelas of São Paolo to seek a practice that would acknowledge the “urgent human problems” and formal structures of global cities (LW, 14). Working in Sarajevo in the 90s, he integrated architectural elements referencing urban warfare into buildings themselves in order to create what he terms “free spaces” and “free zones”: “Into the voids created by destruction, free spaces are injected” (19). A vocabulary of “scabs” (introjected spaces), “scars” (“deep levels of construction that fuses new and old”; 19), “the fall” (the recognition of unpredictable forces such as violent conflict, plane crashes, or earthquakes (20)), and “walls” (peripheries and edges that create “complex, fluid, multilayered societies” (RR, 14) predict “a new and yet-unknown social order” (LW, 26) that is anything but utopian. Several of Woods’s 90s drawings depicting the intersection of buildings and airplane fuselages clearly predate the attack on the World Trade Center in 2001 (confirming Slavoj Žižek’s diagnosis of anticipatory destruction as the “desert of the Real” of the West’s fantasy structures). In later projects in Havana and San Francisco, Woods destroyed boundaries and interior spaces and assumed an uncertain, fluid ground; in all his buildings, disintegration is an element of design, uniting utile and inutile, spaces of movement and of obstruction. This recognition of necessity of the inutile and indeterminate joins Woods’s heterotopian fantasies with the lessons of Las Vegas and Detroit, with the advantage that the destruction at their core is mobilized on both symbolic and material levels. Woods’s prescription for “radical reconstruction” refuses to monumentalize consumer detritus or industrial decay but continues the cultural work of negativity through an avowal—and even a certain pride—of their specific materials forms:

In the spaces voided by destruction, new structures can be injected.…The new structures contain freespaces, the forms of which do not invite occupation with the old paraphernalia of living, the old ways of living and thinking. They are, in fact, difficult to occupy, and require inventiveness in order to become habitable. They are not predesigned, predetermined, predictable, or predictive…. They offer a dense matrix of the new conditions as an armature for living as fully as possible in the present, for living experimentally. The freespaces are, at their inception, useless and meaningless spaces. They become useful and acquire meaning only as they are inhabited. (RR, 16)

Detroit is, in my view, prime territory for the method Woods describes. The elements are in place; all it takes is to mobilize them for new ends—for a reimagined urban architecture. And such initiatives are already being undertaken in Detroit, cannibalizing the monumental discourses of abandoned buildings and reenacting their material forms and spatial disjunctions. One such is the recent Dequindre Gap, a 1.2-mile pedestrian and bicycle path that replaces a disused rail line in an industrial area, connecting two viable zones of activity in the city (the renovated riverfront; Eastern Market) with a zone specifically designed as an experiment in living. The Dequindre Gap is monumental negativity deployed as an inutile freespace that works—a practical case of refunctioning urban negativity after the work of Lebbeus Woods, an opening to a wider discourse on the poetics of ruined space.((Terry Smith, The Architecture of Aftermath (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006).))