Marie T. Hermann in Conversation with Glenn Adamson

at the Simone DeSousa Gallery, Detroit, May 30, 2015

The occasion of the conversation between Marie Hermann and Glenn Adamson was her solo show And dusk turned dawn, Blackthorn at the Simone DeSousa Gallery. The text was made from a transcription of the conversation and has been very lightly edited. Ed

View from Marie T. Hermann’s studio, Pontiac 2015. Photos courtesy of the artist

Glenn Adamson:

The first thing I wanted to ask you about was the title of the show, And dusk turned dawn, Blackthorn. You are prone to poetic titles that don’t necessarily reveal their full content. One of the great advantages we have is that you are sitting here and have to answer my questions. So, what does the title mean?

Marie Hermann:

The title came from this interest, lately, in a moment in time when things change, especially the moment between dusk and dawn when the light makes everything colorless and almost flat, almost as if the room and objects become line drawings. This group of works started with weird line drawings where you can’t really define what kind of spatial relationship it has, and why, it is like a black and white photograph. That was the dusk and dawn. Blackthorn is the name of the William Morris wallpaper I installed on all the walls in the gallery, so the relationship kind of made sense, dusk, dawn, and then black. I like titles with hints of something romantic and beautiful, but also titles that withdraw in the end, and have a tone of sadness or melancholia.

GA:

It reminds me of a title you used at your graduating MA show at the Royal College of Art, in London, where we met. I’m going to get it wrong, but I think it was something like, But I Would Have Followed You Into the Forest. Is that right?

MH:

I would have followed you…

GA:

There was a forest?

MH:

Yeah, there was a forest.

GA:

This was a long time ago, but that was the sentiment.

MH:

Yes, and it was a green piece.

GA:

Yes it was green… But as you can tell it stayed with me that title. It also has the sense of the poetic, a vastly overused word in the art world, but here it fits, because you are engaging in a kind of wordplay. There is an allusive and elusive used of wordplay in your titles. But also, in a more straightforward sense, there is something forest-like in this space, a density of vegetal-ornament, and dusk or dawn light.

I wanted to ask next about creating something natural feeling in the middle of Detroit. Here we are in this famously urban, famously dislocated and often destroyed urban setting, and there is a lot of talk about urban agriculture and other ways to regenerate and green the city, and I wonder how the idea of the natural, in this show, fits into the broader context of showing in Detroit for you.

MH:

It’s tricky. My studio is up in Pontiac and it’s an old building looking over these abandoned lots that are slowly turning into fields. I’ve been here for six years, so I’m not claiming that I am a Detroiter, but there are certain things in this city, in your surroundings that effect you. And maybe you don’t immediately realize it, but slowly. I moved here from London where everything is so tightly packed, and you very rarely see a tree, to suddenly being in a space where green is very much around you in the summer. But the use of this wallpaper was not in anyway a relationship to the city of Detroit. I think there are many interesting dialogues with Detroit and with modernism. You know, Mies van der Rohe has done a number of incredible buildings here in Lafayette Park. So of course, there is that constant of nature and modernism, which is very much what I am interested in, in my practice, and in this show, and this clash between nature and modernism that might not make sense, but I think it does.

GA:

This brings us directly to Willaim Morris. Morris designed this wallpaper to give us exactly the effect we are experiencing. Which is, you take a room and you turn it into this intimate warm glade, that suggests something medieval or faraway, something you can’t quite touch, a dream space. And of course Morris was a famous utopian. He wrote this book, News From Nowhere – utopia literally meaning nowhere of course – and created this visual aesthetic that was about a sense of calm protection. There is all that medievalism that you’re importing into the show. But of course, Morris has often been interpreted as modernist and he looks forward to many of the ideas about production that define modernism in the twentieth century. So why William Morris for you? What are your associations with him? How do you feel about William Morris?

MH:

The wallpaper is a very personal story. My mother inherited a small farmhouse outside Copenhagen and it was a house we would go up to every weekend. It was two very small sixteenth-century houses and in one of the rooms there was this wallpaper. Everything else was white. The house I grew up in, in Copenhagen, had all white walls with no decoration, because my parents were architects and that’s the Scandinavian way, white. So just I remember as a child going into the farmhouse, in the woods, and just being amazed at this wallpaper, feeling that it was the most exotic thing I had ever experienced. And I think specifically because it was a contrast to everything else I knew. And when I moved to England, to study there, I was very interested in the Arts and Crafts movement, and William Morris. I loved the way Morris writes about the joys of labor, and this wonderful Utopia that I know is not real, yet there is still something beautiful about every man’s joy of labor and the joy of working. But at the same time modernism, and the language of modernism, has always been where my work has gone. So I think it has been in my head, this conflict, which is not meant as a negative, “Arts and Crafts” and “Modernism” are, of course, linked in my case. And for this show this is what I thought made sense. And I really wanted to use William Morris for his amazing repetition, pattern, and repetition. The floral against white pieces, where every evidence of the hand is removed. There is a lot with this wallpaper. The flowers are not exotic, they are quite common in the English countryside. So it is also about the everyday, not about the spectacular. In my work I am very interested in the ordinary moments, the non-spectacular. So it made sense from that perspective as well.

Marie T. Hermann’s work in the home of Joy and Allan Nachman.

GA:

So that positions the shelves in this exhibition, with the objects, which we should also talk about, not just the wallpaper…

MH:

(Laughs) Thank you very much!

GA:

The shelves and the objects … before we actually get to the vocabulary of the objects, which is where I want to spend a lot of time, the vocabulary of the objects positions the shelves from being the modernist thing; of course they are these white boxes, very kind of rigorous, and they hit the wallpaper in an unexpected way and they seem like kind of alien presences with the wallpaper, and vice versa, but then there is something almost domestic about the shelves, which you have often referred to in your work. And I suppose your domesticity growing up was in fact modernist. So maybe those two things aren’t incompatible. Can you talk a little bit about the shelf form and why it’s so important in your work, and why it recurs so often and what it does for you as a sculptor?

MH:

One of the reasons I like so much working with the ceramic shelf is that it frames the work in a very formal way, so it becomes a bit like a parergon or a frame around the painting, outside the painting or inside the work. So it is about these moments in time were objects are placed next to each other. It is that moment before they move on as we move on. A shelf made sense as a very domestic thing, where we put things or place things.

GA:

It is formal, yet temporary, or suggests something temporary.

MH:

Yeah, shelves are often objects or platforms upon which we move things around.

GA:

I have been thinking a lot about all these different categories for things that are for showing other things. I wrote about the frame in Thinking Through Craft. We have a show up at the moment about mannequins at the Museum of Arts and Design in New York.1Ralph Pucci: The Art of the Mannequin, the Museum of Art and Design, New York City. And mannequins are things that are meant to show garments, and they disappear when they have the garment on them, but when you take the garment off you realize they are a lot like a sculpture. And then you have something like the mounts for jewelry, or armor. I haven’t had a chance to do this yet, but I’ve always wanted to do a show with medieval or renaissance armor, that has been beautifully, beautifully mounted and you turn it around so you see the mounts from the back. You see the skeletal structure of the armature that it takes to show things. There are many other things like this, and a shelf is one, a plinth is another one. I think it is really interesting and important that you make the shelves. And they’re all ceramic. And they are, themselves, part of the sculptural language but that is quite subtle. There are only a few clues, like the glaze puddle (talking to the audience) which don’t miss. It is my single favorite detail in the whole show. This little puddle of glaze, which clues you that they’re ceramic.

MH:

I think that is the reason why I do them in ceramic. And coming back to the line drawing of things, the minute you can glaze things in the same glaze, objects disappear within that line, or you can highlight certain things by using a shiny glaze. There are so many possibilities of subtle variations you can do with a shelf, and that is why it’s still so interesting for me to work with that format.

GA:

Can we talk a little bit about that idea of silhouette that you mentioned? I love that image you described when describing the title of that time of day, or two times of day, dusk and dawn, where something goes from being a silhouette to being three-dimensional. It’s a beautiful idea. It is almost like a temporal version of the relationship between painting and sculpture, which modern artists always think about. It goes from a photographic or painterly thing, it goes from flat to being real, some thing you can put your arms around. Certainly you are dealing with that in this show. I want to ask you to talk a bit more about silhouette and how drawing the line, if you were going to draw an outline of one of these, relates to the three-dimensional forms you are working with.

MH:

First of all, I will say, I never draw, just to make that clear. I never make line drawings. In my head I do but never on paper.

GA:

Is that because you don’t think you will be able to match the drawing anyway, so why bother or…?

MH:

No, it just never felt natural to me, to draw. When you go to art school you have to have a sketchbook. It is what you have to do, you have to draw every year; you do it, you do it. But it never made sense to me. I make notes and titles, but drawing always felt forced. So at one point I thought, Why?

GA:

Maybe you are effectively drawing in three dimensions as you make.

MH:

You know, I throw and it is such a quick thing. And because I am so interested in how objects relate to each other, next to each other, and in the space between them, drawing just never did it for me.

GA:

Also when you are a trained thrower – this has always really struck me – a thrower is actually thinking about a linear shape. You know you can make pots industrially. In fact, they make pots with these ridged silhouettes basically, one side of the profile of the pot, you just hold it up against the clay and it just cuts the clay off. So you are actually making a three-dimensional form with a linear form, to the line making a shape. If you are trained that way then why would you draw on paper because you form with your hands in a way that is already drawing, so maybe that is something to do with it. But then there are also shapes you are using, like these tall vertical lines, which feel like drawn lines. So what I was getting at was a more open question about how you compose the forms and develop the vocabulary.

MH:

I like arranging things in my studio. And a lot of these pieces come about because I have boxes and boxes of different shapes in my studio that I’ve done over the years or found. And a lot of the time, I have an idea of what I want the piece to be, but a lot of time is spent putting something up, looking at it, then moving it. I think it is like painting in that you just have to try it. You try things out and you change. Color is added and taken away. And different materials play off each other in ways that I can’t always foresee. And things happen the minute you put things together and the artwork develops. It is a long process of arranging objects that come into existence.

GA:

Maybe arrangement has too low of a status as an art process. I’ve been thinking about this because I was just at Allan and Joy Nachman’s this morning and late last night arranging things in their collection. We were just moving things inches on the shelf and it would make this huge difference. And this is something as a museum curator you think about all the time. But if you think about it, Picasso’s collage, or effectively the way Mondrian painted, which was just arranging squares on a white square, and many other examples, assemblage artists of the sixties, or Duchamp assembling a ready-made from two parts, all of that is arrangement. It is not even making. It is arrangement and juxtaposition. So I can see why that would be such a sustained and satisfying process. It is basically like a collage process but using bits that you already have.

MH:

Exactly, and then you make new objects, and try different things. Yet it is also the freedom of not having to decide. Everything, the process, is open, in theory – until Simone opens the gallery.

GA:

When do you decide on the arrangements? At what point does that happen? Is it in this space [the gallery] that it happens?

MH:

It normally happens in my studio, before. But I might push it. And there are certain times when you know that it works. It’s a weird thing but you just know it. And often times they will change, so maybe next time I show these pieces I can change it a little bit. And I like the possibilities of that changeable aspect of them. They are not fixed down. They can be moved, because we move and objects move. And I like that possibility of whatever comes next, but also what once was, and that backwards and forwards.

GA:

This prompts another thing I did want to ask you about, which is the idea of the provisional. And I wanted to ask you about one motif, this stick form with a limp kind of pancake of what I take is resin?

MH:

It is latex rubber.

GA:

Latex that is draped over it, which seems like a kind of dishcloth, lying there or a specimen that is being dried in a laboratory. Like a lot of your forms it could suggest lots of things. So I wanted to ask you where that shape came from? And what I’m specifically thinking about is how offhand it seems. Like it just seems draped here, right now, but it could be somewhere else later. And I guess first of all, Is that the right perception on my part? And, for example, where does that particular form come from?

Marie T. Hermann, Installation detail, And dusk turned dawn, Blackthorn, 2015, Simone DeSousa Gallery, Detroit.

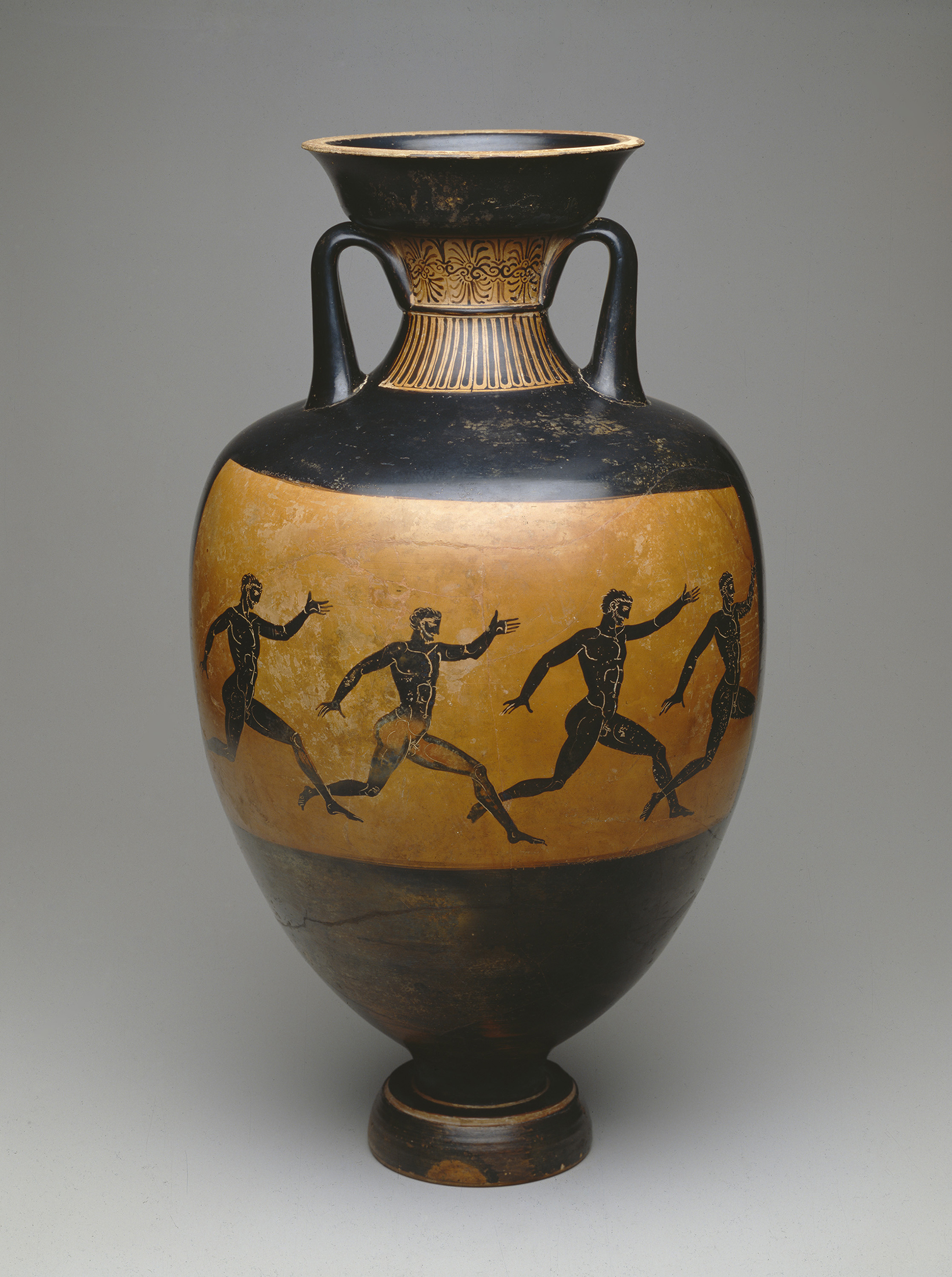

VESSELS FROM THE DIA

A selection of images by Marie T. Hermann courtesy

of Dr. Nii O. Quarcoopome, Co-Chief Curator at the DIA

Cylinder #1 Square

Vessel

Artist: Bodil Manz, Danish, born 1943

2001

Museum Purchase, with funds from Doris and John Brinker and Karen Dark, Graham Beal, George Keyes, Terry and May Birkett, Serena Urry, Pamela L, Watson-Palace and Paul F. Palace, James and Sheri Brunk, Kimberly K. Dziurman, Amelia Chau, Michael Crane, Marilyn Sickelsteel, Matthew Sikora, Nancy Sojka, Valerie Mercer, Terry and Bruce Segal, Iva Lisikewycz, Carol Forsythe, Brian Gallagher and Terry Prince, Rebecca Hart, Michael Kearns, Erin Matusiewics, Michelle Peplin, Leslie Reese, Judith Ruskin, Nettie Seabrooks, Catherine Sweir, Gayla Cullens, Tracee and Jonathan Glab, Michele Ryce-Eliot, and Laurie Barnes and Steven Wang in memory of Kimberly Brinker

Black-topped Pot

Vessel

Egyptian

c. 388/3200 BC

Earthenware

Founders of Society Purchase, Acquisitions Fund

Conical Bowl with Leopard Design

Vessel

Iranian

3500/3000 BC

Buff Earthenware, burnished, painted, weel-turned

Founders Society Purchase, Henry Ford II Fund, the Katherine Ogdin Estate Fund, Hill Memorial Fund, and the Cleo and Lester Gruber Fund

Cylinder #1 Square

Vessel

Artist: Bodil Manz, Danish, born 1943

2001

Museum Purchase, with funds from Doris and John Brinker and Karen Dark, Graham Beal, George Keyes, Terry and May Birkett, Serena Urry, Pamela L, Watson-Palace and Paul F. Palace, James and Sheri Brunk, Kimberly K. Dziurman, Amelia Chau, Michael Crane, Marilyn Sickelsteel, Matthew Sikora, Nancy Sojka, Valerie Mercer, Terry and Bruce Segal, Iva Lisikewycz, Carol Forsythe, Brian Gallagher and Terry Prince, Rebecca Hart, Michael Kearns, Erin Matusiewics, Michelle Peplin, Leslie Reese, Judith Ruskin, Nettie Seabrooks, Catherine Sweir, Gayla Cullens, Tracee and Jonathan Glab, Michele Ryce-Eliot, and Laurie Barnes and Steven Wang in memory of Kimberly Brinker

Black-topped Pot

Vessel

Egyptian

c. 388/3200 BC

Earthenware

Founders of Society Purchase, Acquisitions Fund

Conical Bowl with Leopard Design

Vessel

Iranian

3500/3000 BC

Buff Earthenware, burnished, painted, weel-turned

Founders Society Purchase, Henry Ford II Fund, the Katherine Ogdin Estate Fund, Hill Memorial Fund, and the Cleo and Lester Gruber Fund

Vessel

Artist: Hohokam, Native American

between 900 and 1100

Clay

Founders of Society Purchase, Dabco/Frank American Indian Art Fund, Joseph M. de Grimme Memorial Fund, Lillian Henkel Haass Fund and Clarence E. Wilcox Fund

Shallow Dish with Design of Boys Playing among Lotus

Vessel

Chinese

C. 1200

Porcelain with shallow blue glaze

Founders of Society Purchase, with funds from the Friends of Asian Art and Dr. John V. and Annette Balian

Marie T. Hermann, Shades of days, 2010.

MH:

So I’ve been working with a couple of latexes and resins. And this might sound stupid, but clay, the minute you fire it, is still, it is not moveable in itself. And this contrasts with the rubber, which is just hanging there slightly hovering. If someone moves by it or if the door closes, there will be a slight movement. That contrast between the very still and the unchangeable to this hovering movement, that is neither here nor there, it is just there for a little while. It is not the permanence of the shelf or the stick, it is not going to just walk away, where that other thing could just slide down, could just move a little bit.

GA:

Why is the stick so slender?

MH:

I like it slender?

GA:

(Laughs) It is a great choice, a little like the shape of that puddle. (To the audience) You must all go see the puddle, don’t miss the puddle. But it is like the shape of the puddle because it is quite specific, the shape of it. At least it comes across as specific. I don’t know, maybe it is totally random and what happened in the kiln, but it feels specific. And I think all your choices have that sense of specificity to them, but it is hard to pin down, Why?

MH:

Of course, with that stick over there, it is because I wanted that hovering thing. And the more slender it is the more fragile it seems. The ball next to it has a rim that is just slightly breaking, and they are facing each other. In that piece it is the moment where things are just a little like this [clapping noise] The rim is almost being affected by the rubber moving…

GA:

It also reminds me of something you have done for a long time, which is to juxtapose very platonic solids and bowl forms with blobs, which again are very carefully made, yet carefully made to look random. A great example, right there, a cylinder and a blob. So that is maybe similar to what you are describing with the rubber and the ceramic, something flexible and pliant and something very still.

MH:

These are very interesting moments in our ordinary lives, these contrasting things are played up against each other without making a fuss. It just happens, objects accidently, there and here are my keys and my things. That normalcy, systems of insignificance, that I think are very beautiful.

GA:

That’s a good title! You should save that one, Systems of Insignificance. That’s good. What about the crystalline forms that look almost like natural geological specimens? That’s new in this show, isn’t it?

MH:

Yeah, it is. They are kind of a development of those block forms. Which is a way of looking at tactility and the moment when we touch something, the moment where our hands meet an object. I’m not interested in leaving marks on the objects. I want them just to be about the form, and not about marks, so I trim them in a way that you don’t really know they are cast. It is not important to me that you can see that. So these things were a way of thinking of that space where you touch something.

GA:

So the inside of your hands, maybe?

MH:

Yeah, as it touches an object.

Marie T. Hermann, Shades of pink #3, 2010

Marie T. Hermann, You are my weather, 2010

Marie T. Hermann, You are my weather, 2012

GA:

Why don’t you want the marks of your hands on the objects?

MH:

Because I’m just interested in the shape and what it does on its own. I think I am more interested in the shape as is. And the minute you leave finger marks, I feel that I’m confusing the shape. If I want that I do it in those blocks in that way. It is almost as if I am separating things, in that way.

GA:

I was in college and I was allowed to handle this Chinese pot from the Tang dynasty – so, what is that, like the ninth century? – and it had the fingerprints of the potter on the bottom of it, fired in. So, over a millennium old and you could put your fingers in the fingerprints. And come on, in twelve hundred years people aren’t going to be able to do that with your work?

MH:

But if you break them of course you will. On the inside there are finger marks. They are just hidden.

GA:

There is a strong philosophical weight that is attached to the mark of the hand in ceramics.

MH:

Yes. I’ve just never been interested in that.

GA:

So it is a form of rejection, then. You are not signing up to the idea that the pot is a kind of handwriterly expression of the character of the self?

MH:

No.

GA:

In a funny way, there is something kind of impersonal about the objects. As personal as the overall space is, the objects themselves don’t seem like they’re expressionist in any way or have that intimacy. Although, the overall effect does have a sense of intimacy, which I find rather amazing, and this is something that has always struck me about your work, that the atmosphere is quite soft or sentimental. But the specific objects themselves are quite rigorous, and they have a lot of weight and certainty to them – which I think is a great thing – in this show, probably more than anything I’ve ever seen of yours, probably because of the space that Simone has been able to give you; and the way that the wallpaper has turned it into this total work of art. It really captures that about your work.

One last question before we open it up to the audience. Where does this work take you? So, I know you have a show at MOCAD at the same time, which is very different, and I know that you are rapidly developing a vocabulary that is quite open. So, when you take stock of an exhibition, like this one, what does it make you want to go and do next? Do you know that or is it still a total mystery?

MH:

Well, I’m working on a few things, for the next thing. I’ve bought a couple of really random still-life paintings, or paintings where ceramic occurs in a random way. So there are lots of different things that are going on as well as this working with resin and rubber. I have so much soapstone in my studio, for some reason. But what I’m really enjoying is developing a language in these other materials that contrast and work with the clay, especially the rubbers and the resin, because they are new materials in my practice. Clay, of course, has thousands and thousands of years of history, but to work with material like resin, which is, we’re talking a hundred years or two hundred years max. In many ways, they look like glass, and of course it might make sense to make them in glass, but of course glass has a similar history as ceramics, and I’m really interested in what happens when you put it up against materials that do not have that history, or have a different history…

GA:

… yeah, that are more industrial, and have a specific art world trajectory, like with latex I think of Eva Hesse, for example. Those other associations add to the richness of the work.

Questions from the Audience

Addie Langford:

Sometimes you use color, when do you choose to use color?

MH:

I always have fantasies to make colorful work, and a lot of the pieces start with a lot of color. But in a way it always feels like something that I’m adding on to the shape. So I always see the shape, and then color is something that I am adding to it afterwards in my head. And sometimes I just think that the relationship between the shapes is what I really want, and not the relationship between different colors. And that’s why it is really wonderful to use this wallpaper, because suddenly it becomes this kind of explosion [Marie makes the sound of an explosion] but the pieces when you just isolate them, because of course a lot of them are just really white.

GA:

Although one thing I have to add is that I have never known anybody who was as interested in different colors of white as you are.

(Laughs)

Edmund de Waal, who used to work with Marie, is writing a book about white right now, isn’t he?2Cf. Edmund de Waal, The White Road: Journey into an Obsession (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2015).

MH:

Yes, I think so.

GA:

And then you’ve got Robert Ryman, I guess, and probably some modernist architects, who like white, but you really like white, and different shades of white. And there is a lot of glaze science that goes into that for you, which is kind of behind the scenes, but I’m interested in Addie’s question, because there is a lot of color in this show. It is just that the color is really knocked back and very subtle and low key, and it jumps off the green.

MH:

Yeah and I think again that weird time I talked about, where it’s like colors disappear and it just becomes shades of different things and you….

GA:

Yeah, it’s like the piece you have where there are two very close shades.

Audience Member:

I wonder if by using the Morris wallpaper you don’t essentially divorce your work from the context of what it’s applied to. I feel like in your last show here you used a plywood shelf to separate your work from the white wall. Can you talk a little bit about your work being taken out of context?

MH:

I think the luxury of having a solo show is that you can be in complete control and you can do whatever you want. Of course if you are in a group show you don’t know what is next to you and wonderful things happen with that but you can’t go, “Oh, but I want this,” but you can do that when you can be in complete control of a show. That is a huge privilege because it is almost like you can close your eyes and go, “What I would really lie is, I would like this,” and then you can do it. And of course, so so … and my point to that was that you can use the room in a very different way because with a large show you can determine how you want people to see it, if you want them to be in the middle of the room or the side, and I think that is an interesting position to be in.

Audience Member:

Can you contrast the reception that you’ve received from people who’ve gotten to see your show here, specifically the aesthetic and the view in the Detroit area, as opposed to those who’ve gotten to see your work in Copenhagen or London or some place else?

MH:

Yeah, ok. So I think, less with this show but more so with the other show I did here [at MOCAD],3Marie T. Hermann, Birds in my Hair, in Art X Detroit, MOCAD, April 2015. a lot of the objects I’m working with are relating to functional objects, the cup, the bowl, the plate. These kinds of objects that we so easily, when we see them, recognize as something we have in our kitchen, somewhere. We might not know specifically what it is, it might be a handle that suggests something we are not quite sure, but we read them immediately, like, ok they belong in this part of the house. I think that is the same here as it is in Denmark as it is in London, because it is the same objects we are using. So I think people’s reference to it is quite similar in that way, because the objects that I work with are so ordinary in that way, that our reference to them are kind of the same in many ways. I’m sitting here and I’m like, I must be able to say this is really different.

GA:

Can I ask a variation of the question that Allan Nachman is asking? Do people think that your work seems Danish?

(laughter)

MH:

You have to ask someone else I think, I don’t know.

Yes…I mean…Is it really?!! So, ok, yes. I think…it is the potato feel. No I think Scandinavian more than Danish. I think Scandinavia has had, and has, a history of a certain Scandinavian modernism, that I grew up with, that Anders grew up with. And it is, of course, what you grow up with, what you see everywhere. Denmark is a very small country, we have only 5 million people and if something becomes popular everyone has it. Everyone has Arne Jacobsen chairs. Everyone. So there is a certain aesthetic that if that is what you grew up with it is everywhere, so of course that impacts your work, in many different ways, but, of course, I think that is where my visual language is grounded in. So I think it has a hint of Scandinavian in it maybe.

Megan Heeres:

Marie, I was curious if you could talk a little bit more about the vertical piece right behind Glenn and the role of colors which fade in the work. I want to hear you talk about the fugitive nature of that use of color when you say that it will give you pink for three to five years, but there is more to it than that?

MH:

So, in resin you can color with a permanent color, or, you can color with anything you have in your studio, but it will fade with time. So certain of the resin pieces in the show are in the permanent color and certain are not. And that piece there, for example, already on the opening night it was very, very pink. It was pink. And now it is starting to fade, and it will become less and less pink, and more and more, of a yellowish cream color. And I like that movement. And it is again a little bit the same with the rubber; there is something to contrast the stillness of the ceramic pieces and the stillness of the shelf. With that, even though, of course it is not moving but the color is moving with it. So it is this slow movement in still objects that I find interesting.

When I thought about the show, and this idea that [Glenn] you also mentioned a little bit, that these shelves, these like [clapping noise] this thrrrruppppp [Marie makes zerbert or fart like noise] on the wallpaper, and there are these very foreign alien objects, well not that foreign, but it’s that [clapping noise] this [clapping noise] and in my head there were a lot of times where I saw this wallpaper and there was just these white dots, or something white and rectangular on it. And it just somehow was like this shelf with that, it just wanted to lock, it just wanted to have that contact with it. Because, of course, they are coming out from the wall, so there is just this one little point where they are in contact. And you know when you are sitting down and looking at them this stripe of white just goes around, and I needed that.

Marie T. Hermann, Rönne, 2016. Photo by Galerie NeC. Paris, Fr.

GA:

It relates in my mind to the hanging rectangle. Is that latex as well?

MH:

Yes.

GA:

And I was thinking about the idea of the picture and this reference to a painting that is hanging on the wall, except that you see through like a ghost thing, and I think it expands the vocabulary in a way that, going back to the conversation about the silhouette and things changing from an impression of flatness to an impression of roundness, and they definitely have a part in that.

MH:

Yeah, to come back to your question, this idea that you take things out, and what happens when they are on a white background or … And I think for me this wallpaper, because of this weird personal relationship that I have with it, that it just becomes, the way that I think it makes sense in my head, that is all projected into our own history, that is that. And you might have striped wallpaper and that is yours. And for me it’s also about these, whatever we’ve have…

GA:

Are there anymore burning questions…Ok, last question.

Lynn Crawford:

This idea of being states, it’s like fairytales when something changes state and something becomes wearable forever, and I feel like it is really playful, there is this strange surrealism at work and so there is this rich narrative potential because of the title and because of the fairytale setting with this thing…

MH:

I think that is the really nice thing about titles, you can hint at something, you can either completely confuse, or you can lead, or you can do something a bit in-between, but I think it’s…even though it’s this invisible part, because you can also see a whole show and not look at the title, so it doesn’t have to be a poem but it can be. … I love titles.

GA:

I’m also really glad you raised the concept of the fairytale, because I was thinking about that, too, and the William Morris thing is part of that. He was very interested in fairytales and this paper really suggests that. But there is a big difference between a fairytale and a Utopia. Utopia is a political project that has this drive behind it, and almost a tragic dimension because it can’t come to pass, whereas a fairytale is recognized in advance as something that won’t come to pass. But it also suggests a sense of possibility and escape and a kind of infinite permission to dream. I always, and this is kind of a personal thing, but I always love art that sort of gives you the question, what if things were like this for a while, while you are here with this artwork. And to me this work, your work, always does that. It offers up that question, which is a beautiful thing.

References