Notes on Social Practice

Michael Stone-Richards

[T]he collaborative work artists do to effect public life is intimately linked to the performance and play of conversation – those that we have between ourselves and our audiences.

Doug Ashford, “Finding Cytherea: Disobedient Art and New Publics,” Who Cares, Creative Time, 2006

Unlike its avant-garde predecessors such as Russian Constructivism, Futurism, Situationism [sic], Tropicalia, Happenings, Fluxus, and Dadaism, socially engaged art is not an art movement. Rather, these cultural practices indicate a new social order – ways of life that emphasize participation, challenge power, and span disciplines ranging from urban planning and community work to theater and the visual arts. 1Of course, Dada, Surrealism, and the Situationist International went out of their way to say – protest? – that they were not art movements.

Nato Thompson, “Living as Form,” in Living as Form, Creative Time, 2012

Part of what it is to be a modern artist, and part of the transmission from the modern to the contemporary, is to be self-conscious in the construction of the history of one’s practice. The Surrealists, from the moment of their establishment between 1922 and 1924, set up a Bureau of Surrealist Research; Tristan Tzara, Raoul Haussman, Georges Hugnet, amongst others, very quickly, before the entry of the academics, began to write the histories of Dada; whilst Guy Debord of the Situationist International and George Manciunas of Fluxus would spend much time constructing very precise genealogies and histories. With the advent of performance art Marina Abramović would do the same and eventually begin her own school to ensure the transmission of her thought. It matters little that critics, historians and other actors from the original formations would also add to, contest or upset the often too neat or self-serving constructions; what mattered, and matters still, is that the thinking called art-making was seen to be a reflexive activity and as such an activity that could not, once and for all, be settled, an activity, in other words, that could not be foundationalist in conception. (It is for this reason that Duchamp would have no time for what he called the little recipes of studio art.) We might put this by saying that modern art introduces the idea that all art-practice, and hence all historiography or art, is necessarily a meta-history and meta-practice in the service of a particular meta-theory of art. This is so, with no little irony, even when art-practice seeks to break out of the studio and enter – where? – into The City, having left behind what? – the frame. The latest claimant to the mantle of innovation – aesthetically and ethically – in this tradition of art-thinking has various and varying names as well as various and varying paths of inheritance: public practice, community-based practice, and cultural activist practice.2Here consider Nato Thompson: “The veritable explosion of work in the arts has been assigned catchphrases, such as ‘relational aesthetics,’ … This variance of naming should suffice to tell us that though the practice is identifiable, and clearly so, it is not yet settled on a self-understanding. One can, however, say that two names for this practice have emerged: in the United States the dominant term has become Social Practice, the equivalent of which in Europe is Participatory Art. Both terms speak of the distance from an art of the studio, and of engagement with the audience and “community” – indeed, no term is more used and possibly over-used than the term community,3But cf. the seminal work of Jean-Luc Nancy, The Inoperative Community, trans. Peter Connor and others (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, … and one which is rarely explicitly defined. As Joshua Decter put it in an essay for the Dutch / American exhibition catalogue Heartland:

There has always been some acrimony about what actually constitutes “public practice,” “community-based practice,” and “cultural activist practice.” At times, this becomes a debate regarding who has the right to articulate the interests of a community and whether so-called outsiders have the legitimacy to work with a particular community; this may ultimately be a question of cultivating trust, one of the most complex challenges facing artists who seek to work with, or in relation to, citizens and their life-spaces. 4Joshua Decter, “Art, Urban Rebuilding, Social Justice, and Sustainability: Toward a Case Study of New Orleans,” in Heartland, ed. Charles Esche, …

These key terms, trust, community, relation, citizens, and life-spaces point to a precise space of practice, albeit one whose epistemology and genealogy are not wholly agreed upon.5Cf. Boris Groys, “A Genealogy of Participatory Art,” Introduction to Antiphilosophy, trans. David Fernbach (London and New York: Verso, 2012), … Before Social Practice / Participatory Art became self-consciously such, there was Relational Aesthetics – a term still used by practitioners such as the conceptual and food artist Jennifer Rubell – which re-situated practice away from the studio to the site of production and the audience; but Social Practice, beyond Relational Aesthetics, seeks to engage the citizen, in trust, and to be legitimate, so that its practice will be seen to be of the community, and as such it calls for, even, seeks to facilitate, the construction of a relational subject,6Cf. Elena Pulcini, Care of the World: Fear, Responsibility and Justice in the Global Age, trans. Karen Whittle (Dordrecht and London: Springer, 2013). one that will be the subject of care and as such a subject that sees itself also in relation to its environment, that is, the threatened life-spaces, whence the implicit connection between Social Practice and Biopolitical thought, even if only as a logical entailment and not a self-conscious problematic for all practitioners.7On Social Practice and care, cf. Michael Stone-Richards, Care of the City: Detroit and the Question of Social Practice, forthcoming Artifice/Black … It would take more space to flesh out and make the argument that the subject of Social Practice as a distinctively new practice of thinking in art is an ethic of care, but the time is right, and the material is available for this investigation to begin, not least because this practice of art has become the prevalent and most urgent form of art-practice in Detroit from the Heidelberg Project to the PowerHouse Project, to the role of urban gardening of which Kate Daughdrill and Mira Burack’s Edible Hut can be taken as an exemplar, to the practice of conversation found in Detroit Soup curated by Amy Kaherl, to the experiments in communal living practiced by the Grace Lee Boggs and friends at the Grace Lee Boggs Center. It is, after all, Boggs herself who said in an interview with Democracy Now that “The only way to survive is by taking care of one another.” Here is her full statement:

What happened in 2001 in Porta Legra, Brazil, when people gathered to say: Another world is necessary, another world is possible, and another world is happening, I think that that’s what’s happening in Detroit in particular. People are beginning to say: The only way to survive is by taking care of one another; by re-creating our relationships to one another; that we have created a society, over the last period in particular, where each of us is pursuing self-interest. We have de-volved as human beings. 8Grace Lee Boggs, “The Only Way to Survive is by Taking Care of One Another,” Democracy Now, April 02, 2010, …

It can reasonably be argued that the Diego Rivera’s Detroit Industry mural, 1932-33, in the DIA is the allegory and Ur-scene – even the primitive scene in terms of representation – of Social Practice in Detroit with its hymn to an idealized community of workers and producers where the iconography of the fresco cycle depicts not only harmony amongst workers but a harmony of workers (say, Man) with technology (say, Machine) in “the transfer of energy from raw materials into machines of great power through human strength and ingenuity."9Linda Bank Downs, Diego Rivera: The Detroit Industry Mural (New York: The Detroit Institute of Arts and Norton, 1999), 168. This harmony, and its evocation of a Golden Age in the iconography of the work, the harmony, for example, of the four “races” of White and Yellow (the South Wall fresco) and Red and Black (the North Wall fresco) is an intentional irony within the Detroit Industry mural as the cycle of harmony depicted is in stark contrast to the social and economic realities for workers at the time of the creation of the fresco cycle, for 1932-33 was the height of the Depression. As Linda Bank Downs comments:

Rivera reconciled the concept of modern industrial processes with ancient beliefs at a time in Detroit’s history when industrial systems had failed the worker. The Depression created self-doubt, fear of the future, and blame of the industrialists. The Detroit Industry murals present a modern golden age, before the 1929 stock market crash, when industrial productivity, employment, and wages were at their height and Detroit was a boom town. Rivera created a nostalgia for a culture of work and labor in the automotive industry that had been radically transformed by the Depression, which created a climate where industrialists were despised as being reckless capitalists who abdicated moral economy. Moral economy holds that industrialists have an obligation to control the production, manufacture, and sale of commodities in order to protect the interests of the community of consumers. Moral economy was bankrupt in 1932 – 1933 Detroit. 10Downs, Diego Rivera: The Detroit Industry Mural, 168-169.

stills from Finally got the news

There is a pendant to this persistent topos of an ironic Golden Age, and it is the extraordinary film Finally got the news, made by the League of Revolutionary Black Workers in 1969-1970 and which opens with the verses of the blues song “Detroit, I do mind dyin’”:

Please, Mr. Foreman, slow down your assembly line.

Please, Mr. Foreman, slow down your assembly line.

No, I don’t mind workin’, but I do mind dyin’.11Song composed and recorded by Joe L. Carter, 1965, quoted in Dan Georgakas and Marvin Surkin, “Finally Got the News,” Detroit: I do Mind Dying. A …

The League of Revolutionary Black Workers were workers within the automotive industry of Detroit when they made this film of radical expression. Within two minutes or so of the opening of the film there is an extended use of the iconography of the Detroit Industry mural to situate the continuing struggles of the contemporary work force, to show how at the heart of wealth creation there is waste, the waste of lives, all the more so when human lives, no longer ends in themselves but means, are reduced to resources – as the song says, “No, I don’t mind workin’, but I do mind dyin’.” That their use of the iconography of Detroit Industry leaves out the mural’s iconography of medicine and birth and Calla Lilies is not, however, an accident and points to the internalized fractured and damaged nature of representation, what the late Gillian Rose called diremption, which has been inherited by Social Practice / Public Engagement in its need to gender not only Care but protest in the movement away from aggressivity to connectedness, not only a connectedness to others but to environment as well. (Here one cannot but refer to the essay by Biba Bell on Belle-Isle in this issue of Detroit Research motivated as it is by the masculine gendering of space and protest in Detroit progressive practice along with the marginalization of the domestic.)

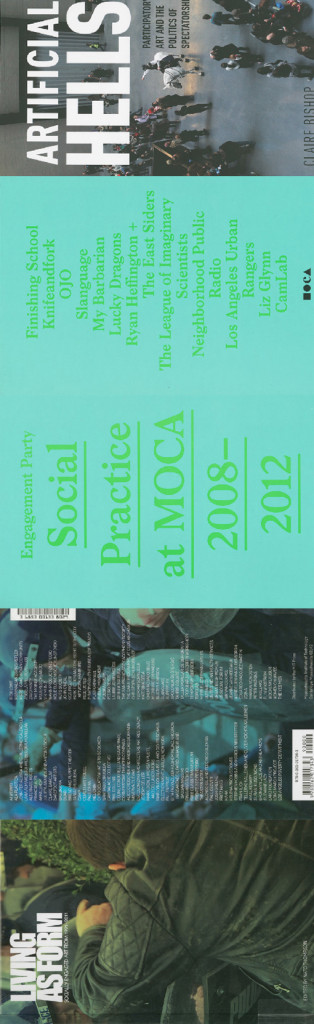

The recent publication of three important and different books bearing on the nature of Social Practice provides an opportunity for critical reflection on this form of thinking and engagement: (1) Claire Bishop, Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship (London: Verso, 2012) is the first book length intellectual history of Participatory Art / Social Practice; The Museum of Contemporary Art, LA, Engagement Party: Social Practice at MOCA, 2008-2012 (L.A.: MOCA, 2012) is the first full self-conscious exploration by a major museum of the implications for its future and institutional identity of Social Practice;12No museum, no gallery, has yet worked out how to put such practices on effective display – see Boris Groys above about the role of documentation in … and (3) Nato Thompson, editor, Living as Form: Socially Engaged Art from 1991-2011 (New York: Creative Time, and Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press, 2012). It would be fair to say that no single organization has become as clearly identified with Social Practice as Creative Time in New York, all the more so after its support of Paul Chan’s Waiting for Godot in New Orleans.

Taking these three books as points of departure, Detroit Research invites critical submissions on the question of Social Practice / Participatory Art for its Spring 2015 issue.

Fig. 15. Ziggurat, East, Summer, 2008 – from Ziggurat and FB21, 2007-2009

References