Photographer of a Revolution: The Girl with the

Camera, the photography of Leni Sinclair

Emi Fontana

All photos by Leni Sinclair, courtesy of the artist

It’s a cold November evening in 1969, in Buffalo NY. An icy breeze is blowing outside; the university gym is packed, inside the air is warm and dense from the smell of sweat and marijuana.

“I want you to hold your hands, ” a member of the MC5 shouts at the crowd.

The crowd obeys.

“Now I want you to take a deep breath in… Now exhale. Inhale…”

White Panthers Party members posing in front of 1520 Hill Street in Ann Arbor, 1970.

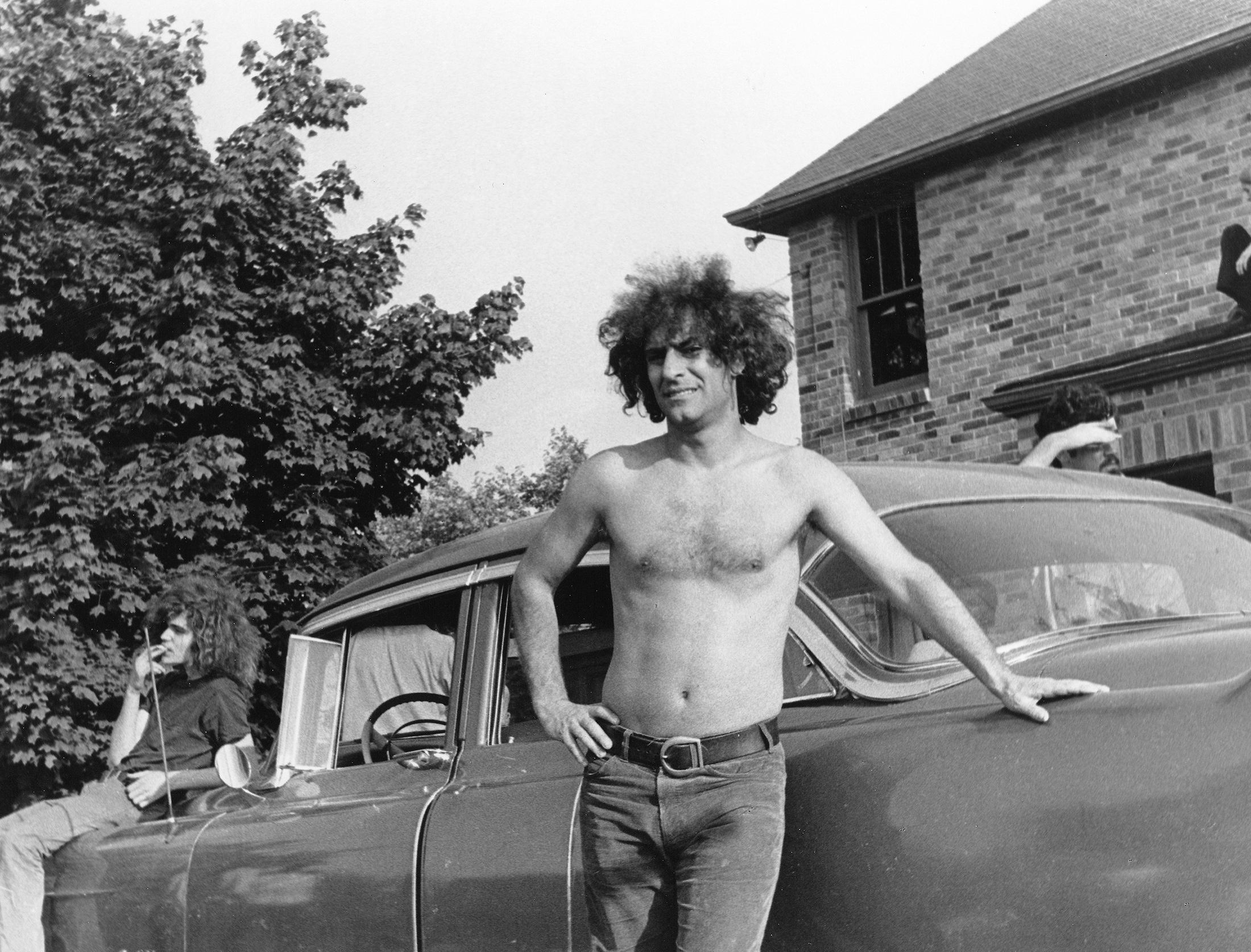

It goes on and on until a thousand young bodies filling the room start slipping into a meditative, hypnotic state. Demarcation lines between bodies fade; the multitude becomes one marvelous revolutionary body lost in deep ecstasy. Leni Sinclair’s camera captures this instant of magic in one picture. In spite of the freezing quality of the medium, Leni’s talent is able to convey the fluidity of that moment as well as many others. We look at the picture waiting for the bodies to start swaying again in perpetual motion. A young and shaggy Abbie Hoffman is leaning bare-chested against a car, looking at us with sexy irreverence. The day before the concert, he spoke at the same conference, haranguing the crowd, “We gotta learn how to breathe together. If you don’t learn how to do that, the government is going to show you how to hang together.” Physicality is one of the first words that comes to mind looking at Leni’s work. She is moving through an incredible landscape of bodies: sleeping bodies, ecstatic bodies, intoxicated bodies, and revolutionary bodies. Before the digital era, it took one click, one breath, to shoot a great picture. In the cycle of a breath, reality gets framed in an instant that can stand for eternity. Looking now at the photography of Leni Sinclair, we are able to perceive the gravity of a moment that has been handed over to history, but we can still feel the flow of life, breezing through it.

Susan Sontag, in her well known essay On Photography, states, “To take a picture is to have an interest in things as they are, in the status quo remaining unchanged (at least as long as it takes to get a “good” picture), to be in complicity with whatever makes the subject interesting.” Leni is the photographer of a revolution; she is interested in maintaining the status quo of permanent revolution in her photography, as well as in her life. Since I first saw Leni’s pictures, many years ago, I met her and heard some of her stories, it’s has been difficult for me not to draw a parallel between Leni Sinclair’s life and work and another great woman photographer, Tina Modotti. It is almost like these two women represent the two halves of the twentieth century, mirroring each other. Both Europeans (Tina from Italy and Leni from East Germany) came to America at an early age, both finding themselves in the midst of a revolution, experimenting with the medium of photography, immersed in the aesthetics of the eras they were living in, getting romantically involved with charismatic men, and constantly blurring the lines between art and life. Tina Modotti, in the epistolary with her mentor and lover, Edward Weston, expressed her desire to reconcile in her photography the dichotomy between the eternal motion of life and the fixity of forms that is peculiar to the medium. Circa forty years later, in Leni Sinclair’s photography, this statement became a fulfilled prophecy.

Black Panthers demonstrating in front of the Federal Building in Detroit, 1969.

Audience at the Buffalo Dope Conference in 1969.

I have seen Leni working. She has a small and bendy body. She has the capability of being there and disappearing at the same time while she is taking pictures; her body squeezes and contorts until she becomes even smaller, and if you are looking for her while she is on the job, often you are not going to find her. She gets lost and confused in the crowd. “Where is Leni? Where is Leni?” When finally, behind the camera, you encounter her eyes again, they are full of love, curiosity and a burning passion for life. Leni’s gaze is feminine and sensual; she infuses her photographs with the same sensuality. She operates behind the camera in a state of perennial complicity with the subjects of her pictures. These subjects are often her friends, lovers, husband, family and comrades, what they are fighting for: equality, free love, drugs, rock and roll, and what they are fighting against: authority, cops, conventions. However, there is gravity in Leni’s pictures, too; in fact, she portrays some very dramatic moments of American History.

John Sinclair and members of the MC5 playing with guns in 1969.

In the late sixties the Black Panther movement agitates the sleep of Middle America, challenging it to transform the American Dream into a nightmare. Black Panther militants are the subjects of many of Leni’s photographs. In one of the most iconic of these pictures, three young African American men are standing on the sidewalk holding white flags with the symbol of the Black Panther ready to pounce. The middle of the banner reads, “Free Huey.” They are asking for the liberation of Huey Newton, one of the leaders of the movement. Two of the young men are wearing berets, the third one has a short Afro, and all of them are bearing very grave expressions on their young faces. They seem to be looking into the void of a future that has been granted by the politics of that moment, but in the force of their determination we can still see hope. In the background of the picture, an older white man simply tries to ignore the whole scene while a young black man in a suit looks at the protesters with an expression of curiosity and questioning on his face. In one of the group shots of the White Panther party, cofounded by Leni, with her former husband John Sinclair, there is a very different atmosphere. The picture is taken in front of their headquarters on Hill Street in Detroit. In this shot, the sense of solemnity that permeates the Black Panther portraits is lost, replaced by an expression of stupor and self-consciousness on the faces of the White Panther militants, who are holding the guns in a manner that looks clumsy, almost comedic. White hippies with guns. We could almost read a sense of embarrassment especially on the women’s faces. The centerpiece of this shot is a woman with her child, close to another woman with a gun and a baby. Leni is behind the camera, but she is one of these women; she is an insider, nevertheless her eye catches all the contradictions of an era. While in the Black Panther movement the possession of weapons had very specific political meaning, which was a different take from that of the WPP. Pun Plamondon, another one of the founders, promoted the use of weapons, or rather, its aesthetic, amongst the WPP militants, from a different point of view: “Get a gun brother, learn how to use it. You are going to need it pretty soon. You are a White Panther, act like one.” Act like one? And what were the sisters doing with their guns and their babies? Leni documents the sixties counterculture from the point of view of someone who is really immersed in that world. Roland Barthes says great photographers operate as mythologists: Nadar of the French bourgeoisie, Sander of pre-Nazi Germany, and Avedon of New York high society. Leni Sinclair narrates the myth of the exceptional season of sixties American counterculture and does it as an insider; actually more than just an insider, a propelling force of that same movement. As great narrators and artists do, while she is telling us the story, she lets another tale emerge from the oblivion, the tale that always hides in the folds of the main history: it is the story of women who lived in a world still dominated by men and by male culture, where women were still casted according to stereotypes, switching from ‘mother earth’ to ‘easy lay’; where they were often put in the difficult position of being revolutionary, operating outside of the law, handling guns, being sexually open, taking drugs like their men, but on top of that, still making babies, being the caretakers of their children, the guardian angels of their men when they got in trouble, becoming the advocates of their liberation when they went to jail. When John Sinclair got incarcerated, Leni became the organizer and leader of the movement for his liberation. That movement is part of American history.

Leni’s real weapon is the camera. She shoots against the oppressors, against American capitalist society, against imperialism, but in a more subtle way that is fully readable to us now, she also shoots against the chauvinism and machismo hidden in the “long-haired dope-smoking culture” of which John Sinclair and several other white men were undiscussed and recognized leaders.

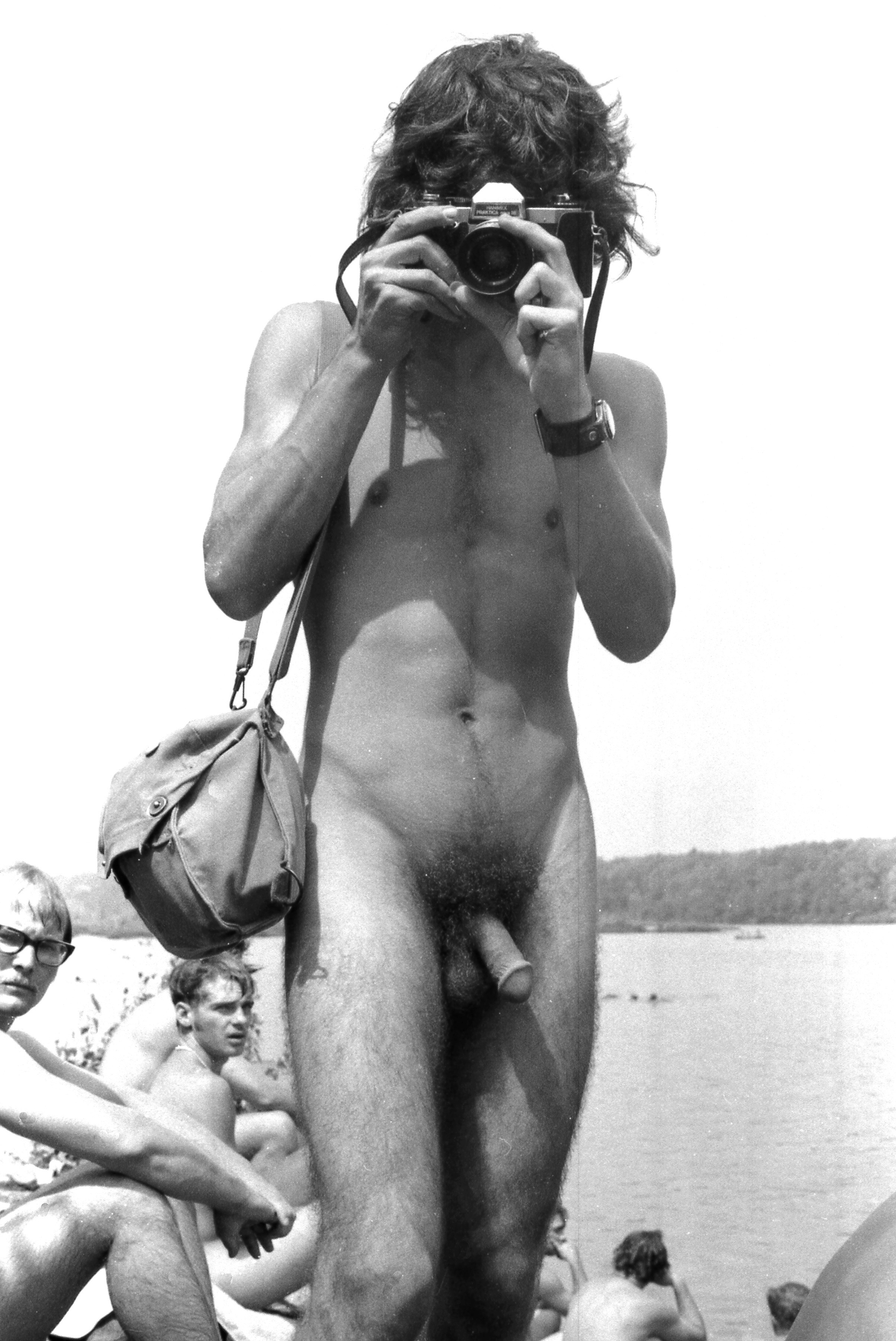

In one of Leni’s pictures we see a beautiful young man, fully naked, portrayed in the gesture of taking a picture, a picture of Leni, while Leni is taking a picture of him. The camera he is holding hides his face. His penis and camera dominate the composition. This picture is taken roughly in the same year as Blow up, the Antonioni movie that celebrates the centrality of the male gaze in counterculture. One decade prior to the pivotal thesis of film theorist Laura Mulvey, that the male gaze focuses on female objects, leaving the female as a passive spectator, Leni created the exception.

In one of Leni’s pictures we see a beautiful young man, fully naked, portrayed in the gesture of taking a picture, a picture of Leni, while Leni is taking a picture of him. The camera he is holding hides his face. His penis and camera dominate the composition. This picture is taken roughly in the same year as Blow up, the Antonioni movie that celebrates the centrality of the male gaze in counterculture. One decade prior to the pivotal thesis of film theorist Laura Mulvey, that the male gaze focuses on female objects, leaving the female as a passive spectator, Leni created the exception.

There is another picture that we could read as the negative of the one described above: Leni has pointed her camera right inside the empty space of a rifle barrel that constitutes the main focus. Out of focus with a blur effect, the silhouette of the holder of the weapon emerges from the background with long black hair. Music was all around then, mainly rock and roll. One of the greatest intuitions of John Sinclair was that pop music was the best way to influence youth’s way of thinking politics. He didn’t succeed, but the intuition was brilliant and convinced the F.B.I. The MC5 were the minstrels of the revolution. The solidarity between the Sinclairs and the band began on August 7, 1966, with Leni literally unplugging them during a concert to celebrate John’s release from his first incarceration for a minor marijuana offense. The MC5 started to play so loudly that Leni was afraid their neighbors would call the police and John would be taken right back to jail. She first tried to tell them to lower the volume, but of course they couldn’t hear her, so she pulled the plug. John became their manager and Leni their in-house photographer, “Just because she had a camera,” as she recalled. At the time, electric guitar was the other weapon in order. In many of Leni’s pictures, guns and guitars are brandished at once, while the stereotype of the white male rock god was growing out of 1960s counterculture with the manhandling of electric guitars being an integral part of it. The magazine Rolling Stone strongly contributed to the creation and popularization of that iconography. Founded in 1967, until 1969, most of the magazine covers were shot live, in situations in which the photographers were in psychological proximity to the performers; however, already in the middle of that same year, they started to portray the musicians in studios. The pictures were often cut out on white backgrounds that, until now, remain the trademark of Rolling Stones covers. In one of the most extensive survey shows of rock photography, held at the Brooklyn Museum in 2009, Who Shot Rock & Roll: A Photographic History, 1955 to the Present Leni Sinclair’s work was not included. Her photography might be at the root of the genre, and beyond, just before it sclerotized into the frozen iconography of white masculinity we all know about, which is especially startling because rock and roll was born on the backdrop of the civil rights battles against racial and gender segregation. Leni portrays the myth, but once again her gaze plays with it with irony and sensuality as she is catching the myths off guard, literally unplugged, bringing the contradictions to surface.

The solidarity between the Sinclairs and the band began on August 7, 1966, with Leni literally unplugging them during a concert to celebrate John’s release from his first incarceration for a minor marijuana offense. The MC5 started to play so loudly that Leni was afraid their neighbors would call the police and John would be taken right back to jail.

Abbie Hoffman at the Underground Media Conference in Ann Arbor, 1969.

Cynthia Plaster Caster in Ann Arbor, 1968.

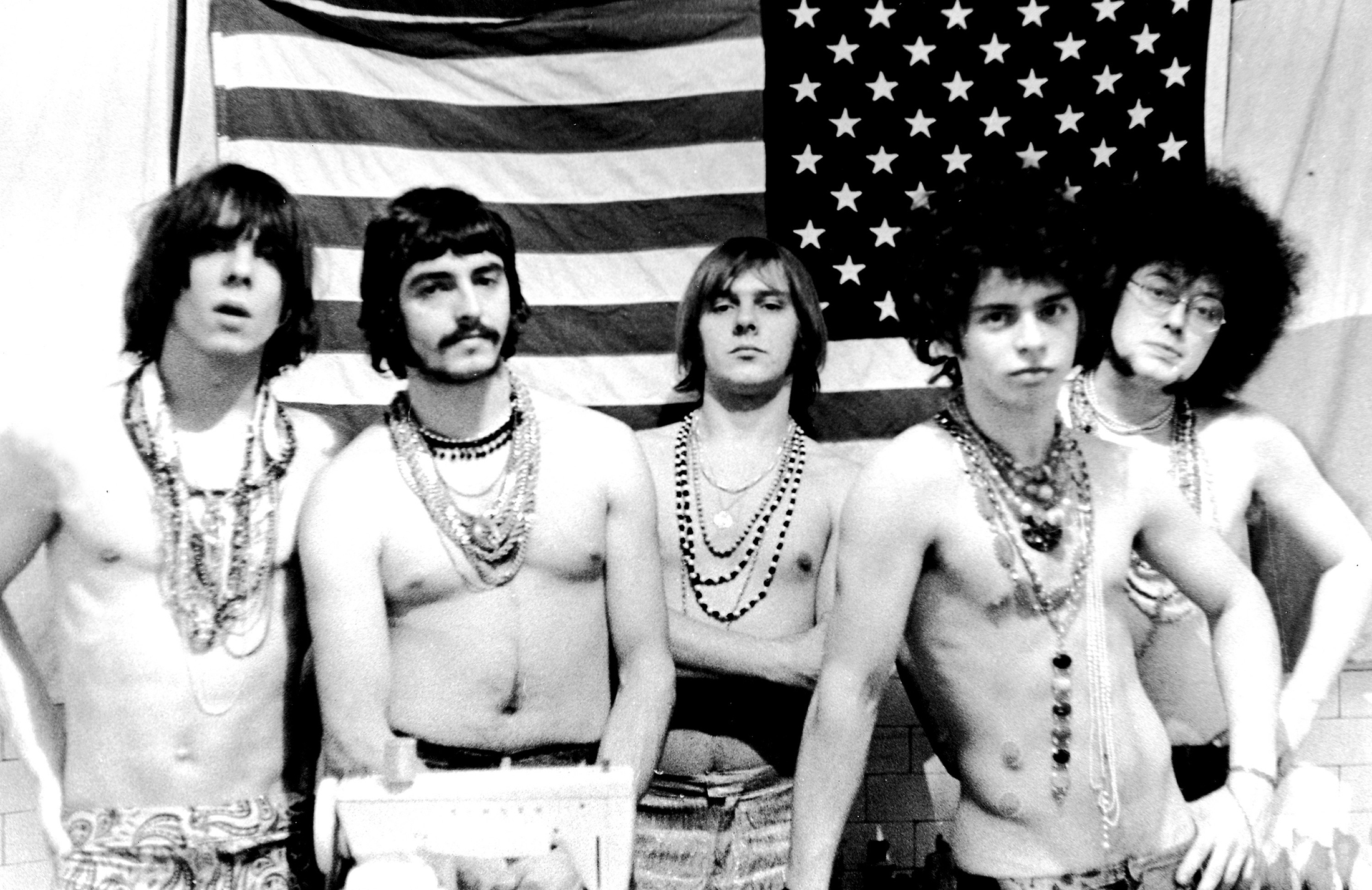

The MC5 are quite a phenomenon in rock-and-roll history and very much due to the touch of John Sinclair. They were the only rock-and-roll band that officially represented a political extremist group, actually recruiting militants through their concerts. Many critics regard them as precursors of punk. Their stage acts and sets were also very peculiar. The use of the American flag as a background and the toting around and brandishing of rifles made them a unique subject for Leni’s camera. But once again the qualities that are coming through the grain of these pictures are very different from what we could expect. There is an intimacy and sweetness that is mostly alien to the way rock-and-roll photography is intended now. Often Leni captures boyish expressions on the band members’ faces that are sexy and endearing, very far away from the rock-and-roll god stereotype. There is a great picture of them showing their biceps and winking at the camera and another one in which the band is posing with the background of the American flag. They are holding coffee mugs and on a table in front of them, the centerpiece is a sewing machine. If MC5 are considered predecessors of punk, Leni’s pictures definitely contribute to this critical reading. Punk code is far more complex than traditional rock and roll, especially when it comes to gender and role-playing, as well as the importance of DIY (do it yourself) culture. On gender and DIY issues, we can certainly consider Cynthia Plaster Caster from Chicago a bright star. Cynthia describes herself as ‘a recovering groupie’ and we can believe that in good faith she assumed that going around with a few helpers to cast erected penises of rock stars was part of her recovery program. Leni took a great portrait of Plaster Caster: Cynthia is holding and showing some of her creations to the camera, looking like a bulimic presenting some kind of cakes she is used to binging on. Plaster Caster art works and gestures are much more subtle and interesting than what she herself thought. Frank Zappa definitely was of the same opinion when he became her patron, but was smart enough to refuse to get casted.

The MC5 in Detroit in 1967.

It seems to be a common threat for women coming out of the sixties counterculture to be really modest about their contribution to that history. When you talk to them, they will tell you that they just happened to be in the right place at the right time. Leni would tell you that all of that happened just because she had a camera. Maybe she didn’t know it then, but today through her pictures we can have a more profound reading and understanding of a pivotal moment in the cultural history of the West.

I was born in the early sixties and came of age thinking that the sixties was the coolest time. I would have loved to be a young woman then, to grow my hair long and live in a commune. I almost did anyway. As many people of my generation, I idealized the youth movement that came before mine. We now know well how tough the position of women in the countercultural movement of the sixties was, but undeniably those were times of radical transformations, especially about female roles in society. Through her life and through her photography, Leni Sinclair has been a witness and an agent of those changes. We look at her photos now and we can see time shifting. Being able to convey these changes while they were happening is certainly one of the main qualities of her photographic oeuvre.

Leni Sinclair just happened to be a girl with a camera back then, but she turned it against the MC5 while they were singing: “I saw you standing in there /

I saw your long /

Saw your long hair

… All I want to do now, girl /

Is look at you looking at you baby/Look at you, looking at you baby /

Yeah, yeah, hey…”

Fred Smith of the MC5 playing with a rifle in 1969.