Scott Hocking’s Long Look at the End of the World

Glen Mannisto

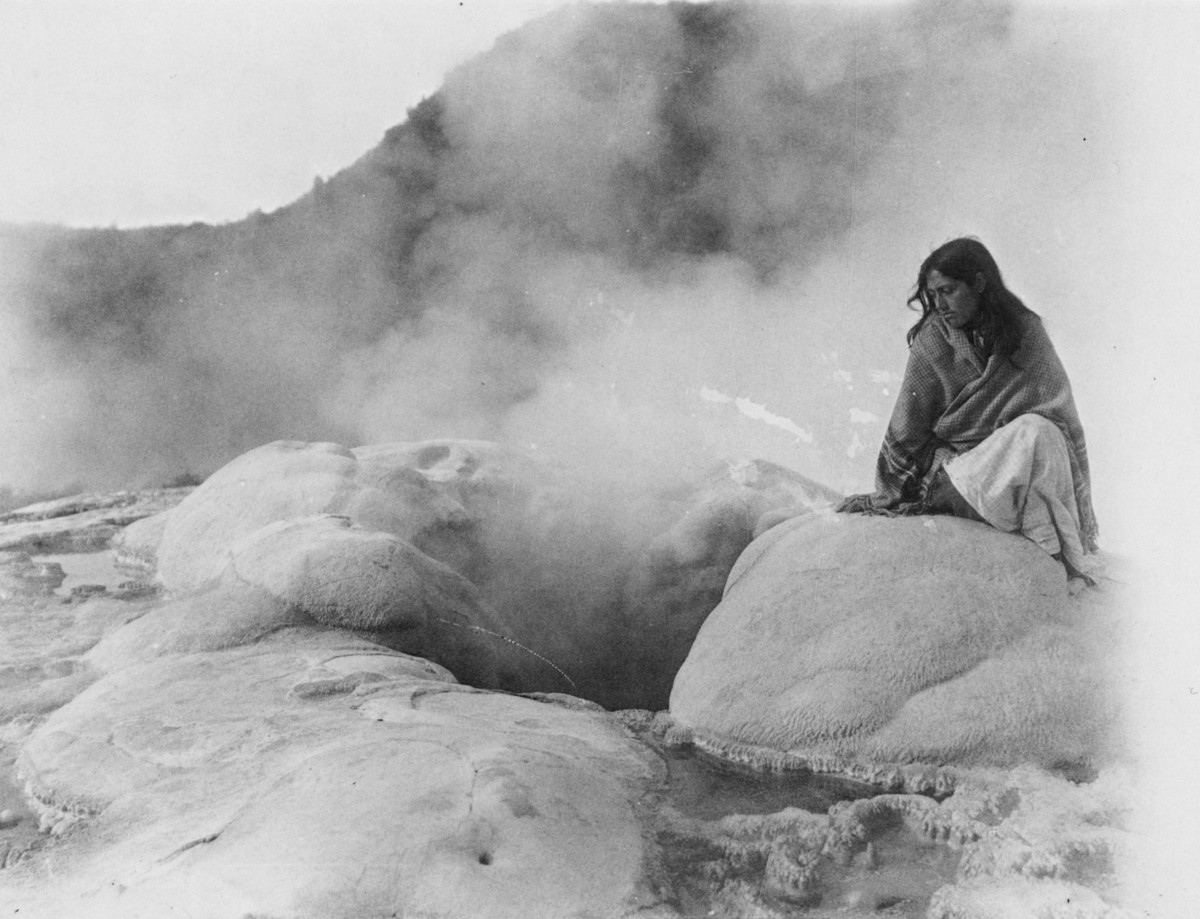

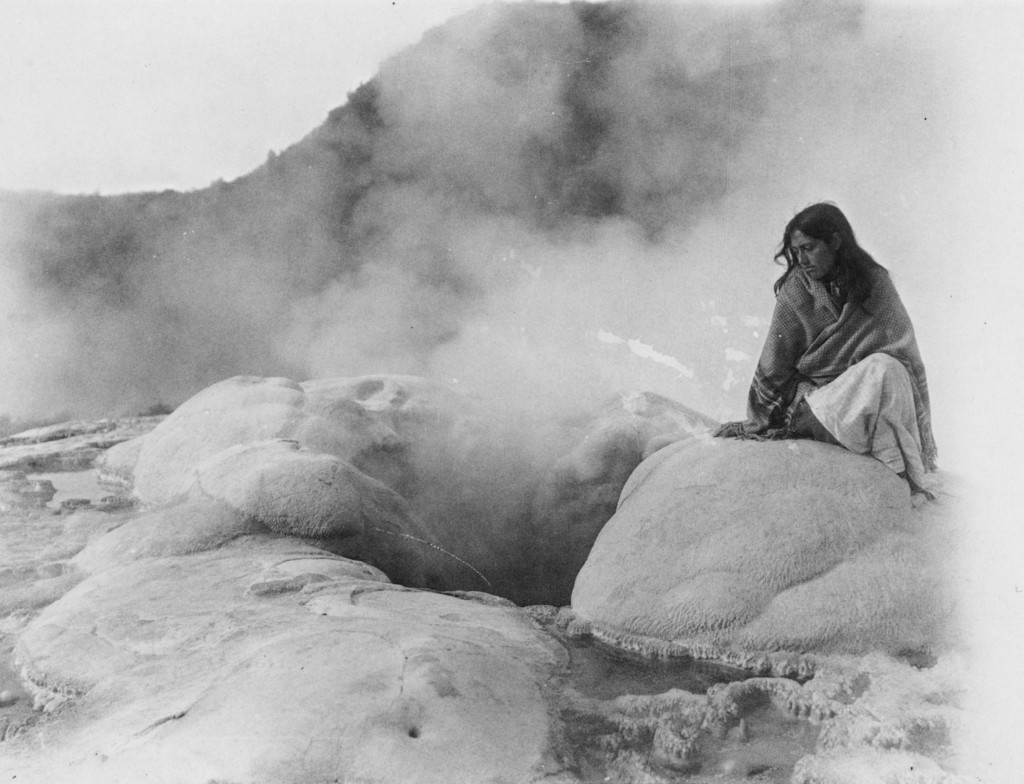

Image courtesy of William Henry Jackson

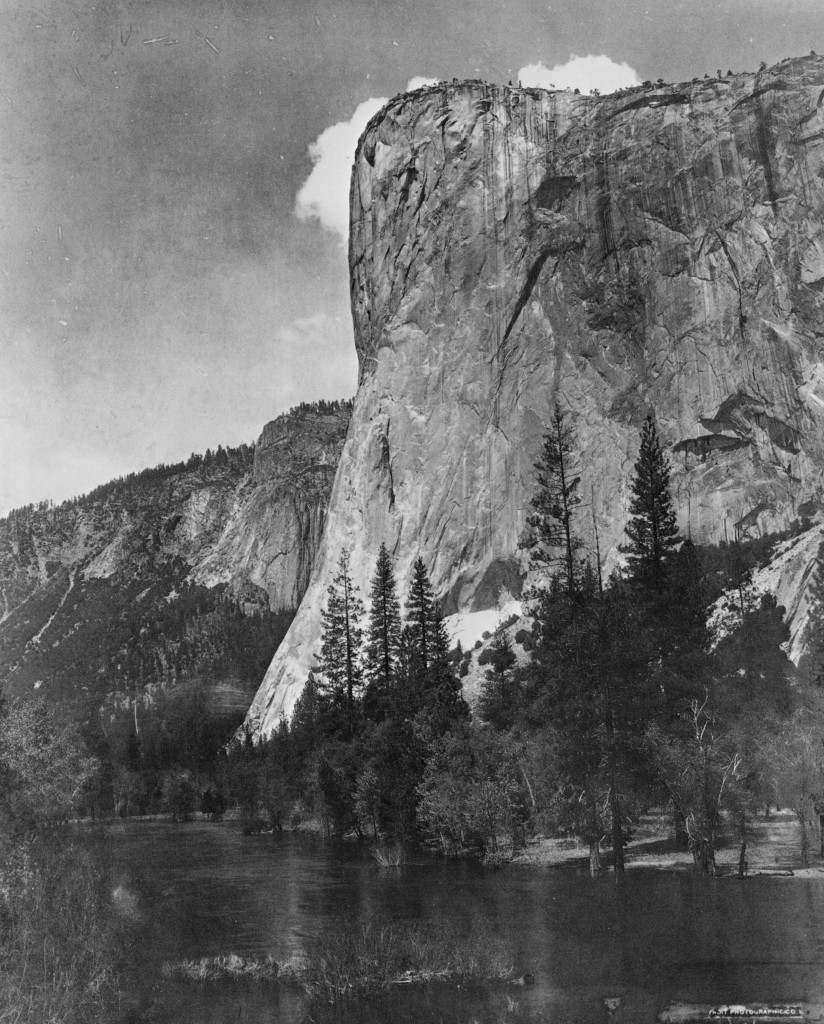

The camera, more than the windscreen of the car or any other revolutionizing nineteenth - century machine, urbanized the planet. Rivaling, if not surpassing, landscape painting, it became the portal through which much of the unknown, exotic world was visualized and imagined. Through huge box cameras, hauled by such intrepid Romantic explorers as photographer William Henry Jackson of the Detroit Photographic Company, the eroticized secrets of the faraway became exposed. The voluptuous flora and fauna of the interior of Florida’s everglades, the craggy mountain peaks of the Rockies, or the comely “natives” of Maori were no longer chaste visions, but material for the gaze of armchair travelers. Detroit’s own modern-day Jackson, artist Scott Hocking, has made a career of exposing stunning views of the remote interior of the city’s now infamous derelict urban landscape. In work often and pejoratively referred to as “ruin porn,” he has photographed the inexhaustible evidence of capitalist exploitation. And while some photographers have been content to document the icons of Detroit’s industrial demise --Michigan Central (railroad) Station, the Michigan Theater—and leave it at that, Hocking has for years, roamed solitarily the vast area that is the city as if it was his studio, “trusting myself, with no particular product in mind,” to shape a body of work—sometimes photograph, sculpture, assemblage, objet trouvé -- that is anything but porn, always transformative and on the way to becoming iconic.

Hocking has a broad literary vision of how to treat his subject; however, his is not based on the messianic notion of “Manifest Destiny” that compelled nineteenth-century photographers to capture the ravishing beauty of the Wild West. He works in open-ended series with a kind of formalist arrangement of objects--abandoned boats, cars, houses, factories--documented, or sometimes appropriated, in the “studio” he “roams,” and seems to grid the open landscape as he builds taxonomies of objects that suggest deeper issues layered in the space that was Detroit. While documenting change and transformation caused by force of nature or man, Hocking himself becomes, as artist, an agent of transformation and consciousness.

The End of the World, a recent exhibition at the Susanne Hilberry Gallery in Ferndale, Michigan, typifies Hocking’s work strategies, and as a total installation underscores the wonderfully obsessive nature of his art. Among the many parts of installation are two sets of large, archival-pigment prints of his serialized projects, documenting work that he has done outside of the cultural confinement of the gallery. There are night photos — Detroit Nights — of moments in the urban darkness lit by a street light or two, wherein stands a lone remaining building or house from a once thriving neighborhood, which appear as stage sets awaiting players who will never reappear (see Fig. 4). Each of the photos in Detroit Nights has a different referent: some memorialize an important historical site such as a famed trailer park on the river, or an ancient native burial mound, or a whacky architectural site such as Stanley’s Chinese restaurant. I-75 Over Carbon Works documents a beam of light seeping through a crack in the divided highway overpass above as if it were a Mayan astronomical earthwork. Each photo suggests a fleeting memory of Detroit’s regional peculiarity.

Image courtesy of William Henry Jackson

Visions of the End of the World

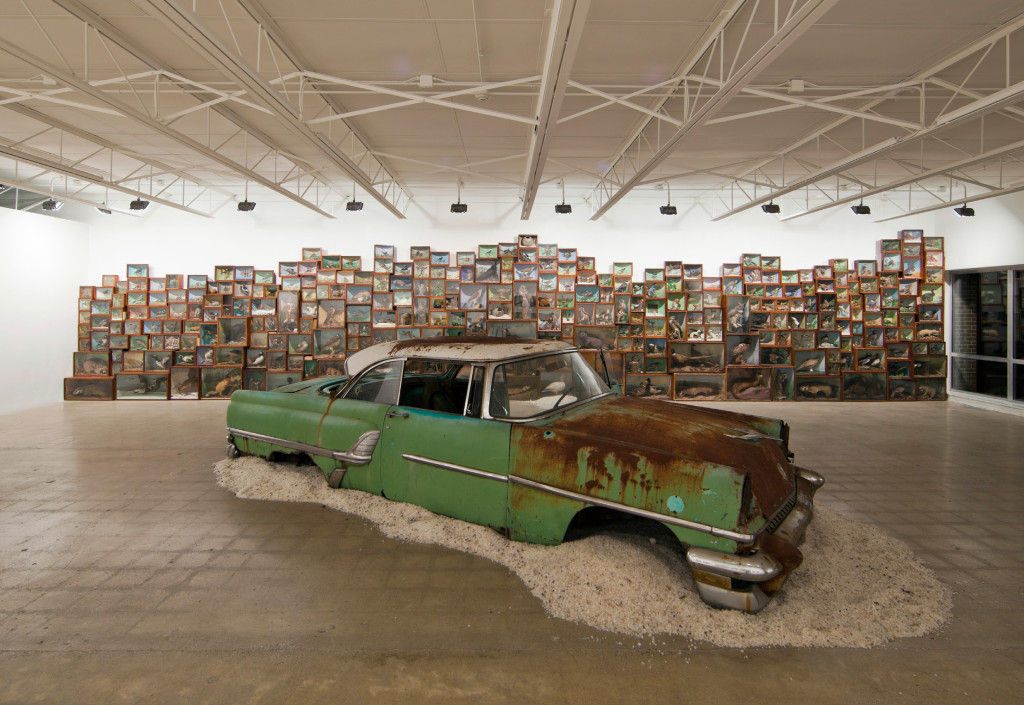

A series entitled The Egg and MCTS features photos of the baroquely trashed hallways of the Michigan Central Station and of an ephemeral monument that Hocking composed in the shape of an enormous egg (see Fig. 20). Elegantly crafted of shards of marble from the vandalized walls of this once-upon-a time cathedral of commerce, the egg, like the majestic pyramid of wooden floor blocks Hocking created in the Fisher Body Plant and the tire pyramid made of thousands of tires “dumped” in Detroit’s vacant lots, will eventually be demolished along with the building. The idea of continuous change and transformation is a constant in Hocking’s work and it occurs, like all good time travel, without nostalgia and on an astronomical rather than diurnal stage, and his own work is part of it. Hocking’s ephemeral, pyramidal monuments have become a significant motif in his work and suggest his interest in archaeology, as well as the spiritual and alchemical research that underlies his work. The End of the World, from which the exhibition gets its title, is a “spiritual pyramid” of intriguing books collected on the subject of cosmologies and doomsday reports of various cultures and thinkers occupies one of the walls of the gallery. (Perhaps not coincidentally it was installed on the celebration of the end of the world of the Mayan calendar.) Mercury in Retrograde, a whimsical astrological pun, is a mixed media installation, composed of a rusty 1955 (probably the glory year of Detroit automobile production) Mercury car, resting wheelless on a pile of rock salt (see Fig. 17). With a gorgeous patina of rust and oxidizing turquoise paint, the Mercury is an astonishing moment and image in the evolution of all cars and human production, and it suggests Hocking’s mythic sense of time. Ironically the rock salt was more-than-likely mined under Detroit in its enormous salt mines, and the installation monumentalizes how Detroit, historically, continuously undermined itself. Overall Hocking’s installation has a quixotic and romantic scale and at the same time possesses a visual literacy reveling in quasi-systematic and formal compositions that permit diverse readings whether as pun, underlying myth or the cosmological.

The Bad Faith of Graffiti

Bad Graffiti, released the night of his Hilberry Gallery opening, is a book of Hocking’s photographs of not just any graffiti, but bad graffiti punctuating the city, and expressing not the artistic genius of the street artist calling out for attention from every blank wall, but a subtext of everyday life. In a prologue, Hocking defines the multiple possible meanings of “bad,” one of which is “naughty,” and hilariously many of the drawings are raucously pornographic, mocking the idea of “ruin porn.” A preponderance of hastily drawn penises seems to adorn every empty wall and abandoned house, and testifies that we have entered a libidinous zone. Occurring less frequently, naturally, are the desired vaginas (usually drawn with a little more TLC). Throughout his work Hocking documents the graceful but savage power of nature in dismantling the urban grid, but here it is realized as a literary force mocking the structure of the city. In the first image of the book, Close My Ass, Hocking finds this untranslatable one liner on the synthetic, rusticated, concrete block wall of a party store advertising Budweiser Beer (see Fig. 24). It is pure poetry, startling and violent and funny, that has no corollary in the spoken or the written language we use. It’s an endgame statement that says it all — much better than Turn Off the Lights!

On another wall, beneath a hand-lettered and illustrated sign on an appliance store wall are the words “STOVES & FRIGIRATORS” with a “frigirator” illustrated in two-point perspective and a clothes dryer (not a stove!) also illustrated. In response to this benign domesticity are the freehand, spray-painted words “EAT ME.” Short, succinct, and brilliantly dark, this is a response that is more devastating than the usual overblown, spray painted gang tag or egoistic marking that we see in most graffi ti. Bad Graffiti — from Black Dog Publishing of London, a press that features “art, architecture, design, history, photography, theory and things, and that celebrates the layered processes of cultural production” — is a felicitous publication for both Black Dog and Scott Hocking. It suggests the nuanced engagement that he has with his work and the broad range of his vision. If the whole fraying fabric of the city is Hocking’s studio and his process is this chance-driven, drift through the palimpsests of the derelict, then he is as much grammarian as artist, archaeologist as photographer, scholar as monk, and perhaps a good deal of each. Bad Graffiti is way smarter than the good graffiti they call art.

Image courtesy of William Henry Jackson

Fig. 17. Mercury Retrograde, Scott Hocking, 2012.

Installation view of The End of the World, Susanne Hilberry Gallery.

Fig. 18. (above) Tire Pyramid Lawn After Removal, (below) Tire Pyramid with Man and Dog, Scott Hocking, 2006.

Images courtesy of the artist.

Fig. 18. (above) Tire Pyramid Lawn After Removal, (below) Tire Pyramid with Man and Dog, Scott Hocking, 2006.

Images courtesy of the artist.