Tony Hepburn at Cranbook Academy of Art

Marsha Miro

Walking into the main Cranbrook Art Museum space in the Fall of 1993, while Tony Hepburn was doing his installation (see p. 279) Do Not Think About the Blue Door, was a revelation. As the new artist-in-residence in the ceramics department, Hepburn was clearly declaring his relationship to clay. While the piece included a 3000-pound pot, he was saying he wasn’t essentially a potter. He was a conceptual artist, concerned with site, context, material properties, language, and how all that would shape a work of art made of clay. Ideas first. Then the piece. Then the reconsideration of what was made, usually in drawn form and from memory. The installation was about visual thinking. See the piece first. Don’t think about it. Your perceptual response will lead to ideas and language. Thinking comes out of seeing. Memory is where understanding is formed. Understanding is not a retinal experience.

That was the way Hepburn’s work evolved from 1970-76 when he was part of the Art & Language movement in his native United Kingdom, a group often credited with being among the first conceptual artists. While the group was primarily fine artists Hepburn was one of the few who took this approach with clay, bringing it to the Eastern United States when he taught at Alfred University in New York State from 1976-1992 and then to Bloomfield Hills. This essay focuses on his Cranbrook work.

Blue Door was finished the day the exhibition was over, because the process of making was what was on display, not a product. And then the installation was dismantled. Students, visitors, faculty—everyone watched Hepburn, the master sculptor, shaping. He paced around the piece, constantly eyeing what was going on from all angles to see how the parts related to the space and each other. He worked and reworked. He removed the hallowed Eliel Saarinen-designed museum doors, interrupting the well-established and taken-for-granted relationships. He was very particular about how his huge 18-foot high, Yves Klein-blue doors, opened to frame the main section of the installation. The view centered on the big pot bordered by a bamboo scaffold of carefully crafted ladders on each side, structures that led to another ladder in the middle used by Hepburn to descend into the top of the pot. The scaffold was a gate-form, a structure Hepburn returned to frequently, using it as an entryway arch, a frame and historical architectural element. Here a shape that focused the viewer on the “pot.” Sometimes Hepburn was inside the big pot, hidden so viewers commented without knowing he was there. Other times he could be found shaping the clay by hand, happily ensconced in piles of clay. The process could be messy and he reveled in its primordial connotations. Another 1000-pound pot was centered in the space, both pots carrying in their mass, a sensual and visual description of their material properties and how they were made. One hundred press molded masked heads, cast from an old mannequin, were lined up on shelves, each individualized face looking like an unseeing witness at the site of something eerie, abstractly adding elements of history and story and mystery. Because they were masked, the idea was that these heads weren’t about seeing with their eyes, but rather perceiving with their senses. “Memory is incredibly important in terms of looking and understanding art,” Hepburn said.

Tony Hepburn, Installation, Do Not Think About the Blue Door, 1993. Cranbrook Art Museum. Photo Tim Thayer

Tony Hepburn, Installation, Crucible, 1998. Dennos Museum Center.

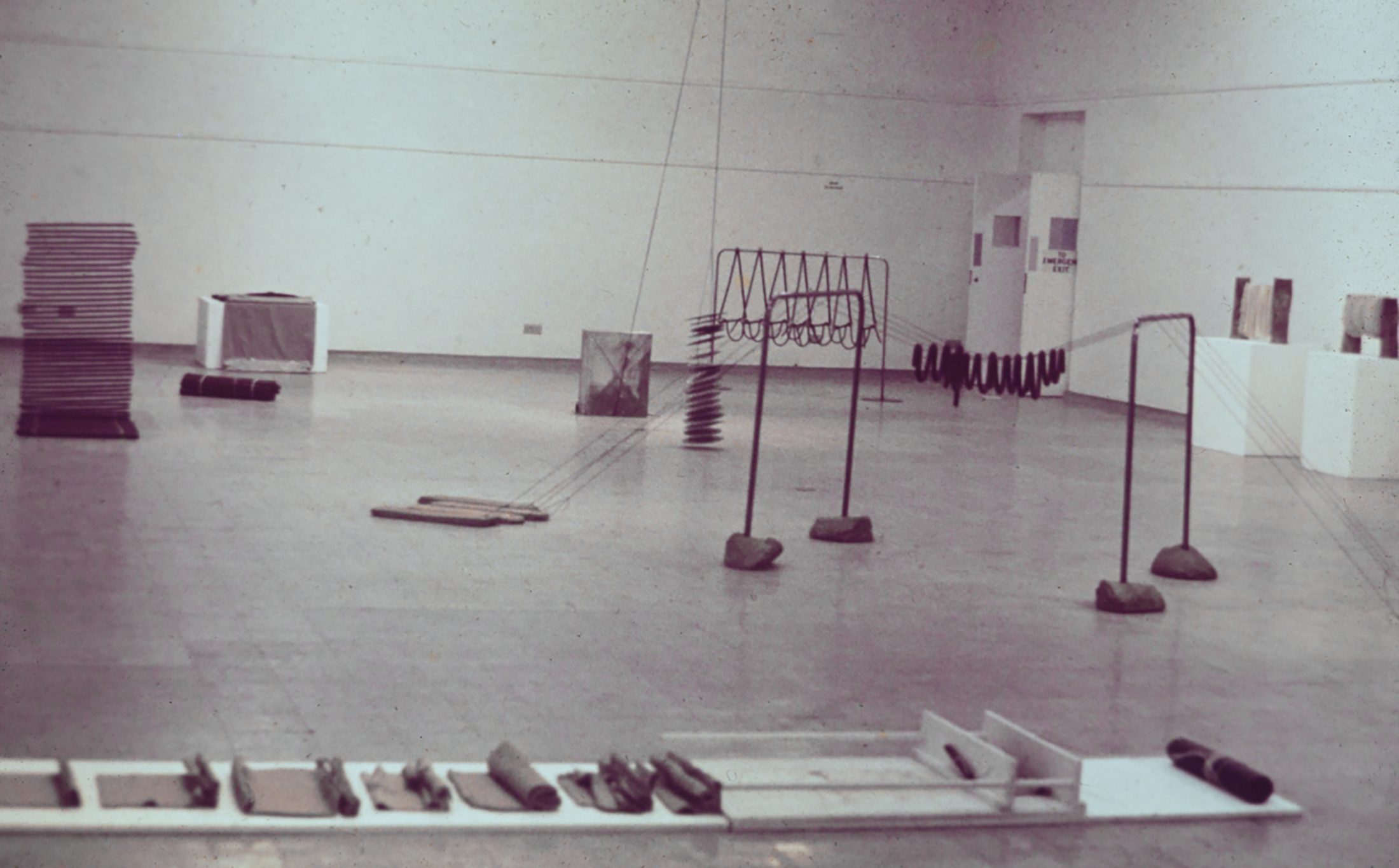

Tony Hepburn, Installation, Recent Work (Materials Pieces), Camden Arts Center, 1971.

Tony Hepburn, Cup Piece, 1979, ceramic.

Pots, sculpture, tools, found things, simulacra—many elements were in the work. Just not by themselves. Hepburn said the piece was about “how we are affected by subversive and subliminal information.”

In those days someone might have connected the word “hybridity” to Hepburn’s work, because it was an accumulation of so many variables. It wasn’t a deconstruction or reconstruction with the order that implies, but a gathering. It included relationships to his antecedents: The early twentieth-century British potter Hans Coper; the late twentieth-century English land sculptor Richard Long; and Hepburn’s great friend, the remarkable clay artist Robert Turner, who taught with Hepburn at Alfred University, that bastion of contemporary clay art. Coper made gorgeous pots that included figurative, Cycladic and Greek elements in their reduced forms. Long walked the planet making paths and leaving traces of human occupation that added ritual and aesthetic change to the landscape. Turner was there with Hepburn, his voice a constant companion, saying things like: “I am doing what we perhaps are all doing—searching, hunting…This search has a deep meaning and significance, and the finding is in the process, not necessarily in the result of it. The more nonbeing a person can take into that process, the more power that is brought in.” Turner and Hepburn were both seeking the ineffable using a solid form. For Turner it came from spiritual connections. For Hepburn it was from the conceptual Art & Language base. Hepburn brought the rigor of primary symbols – the meaning attached to words by random associations – to a piece. Hepburn said: “The whole idea of permanence has disappeared from my work. Everything is temporary. My students call it ‘the dumpster of culture.’”

Change, chance, risk versus determined forms, the continuity of pre-history, written history and contemporary photographic and digital worlds; human instinct, sensual pleasure, intellectual dialectics; Hepburn was looking for truth in late twentieth-century art by bringing it all together. When you were in his presence you knew he never compromised. You understood that he was always curious and vulnerable and resolute. His voracious brilliance led him to stand precariously at the juncture of it all to synthesize these elements in his art – seamlessly, beautifully. This conceptual co-mingling was something new the way Hepburn did it. As Glen R. Brown wrote in World Sculpture News (Autumn 2003) of Hepburn’s later word- based works, Hepburn’s “Word sculptures (were) object and subject. His sculptures became sites at which the purely abstract realm of language and the material plane of ordinary objects were fused into a new hybrid state.”

Tony Hepburn, Installation, Do Not Think About the Blue Door, 1993. Cranbrook Art Museum.

If one were to trace Hepburn’s evolution, it would be of a career heralded in the clay world, but one without fanfare. As an artist working in clay his audience was not those looking at fine art, even though he was involved in the same territory of exploration, but with a different material history. In the clay world he was respected as an important artist, ceramicist, and educator. It was the teaching that took him from place to place over his lifetime, and landed him finally at Cranbrook, in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan. Roy Slade, the director of the Art Academy tried to get Hepburn to leave Alfred when Hepburn taught there. Finally, it was Slade’s successor, Gerhardt Knodel who lured Hepburn to take over the department. It was Hepburn’s conceptual approach and his installations that Knodel believed would bring that department forward into the realms being explored by the other artists-in-residence at Cranbrook.

While Hepburn said he was ready for a new challenge after 16 years at Alfred, part of the attraction for him was the promise that Cranbrook would be constructing a new studio building for the departments of metals, fiber, and clay. He also wanted to be in an educational environment where all disciplines were equally matched. At Alfred, ceramics were central and the fine arts not as strong; as a result the synergy wasn’t as intense.

Hepburn’s philosophy of teaching didn’t change from place to place. He said: “I never taught anyone about technique. We had equipment that was capable of forming the material. If someone needs to know how to make something they will figure it out […] Half of my emails every day are from former students, which is wonderful. I don’t think it’s what you say. It’s how you are with them. It’s the relationship that you build. I don’t think I’m a teacher. I’m a mentor […] I never ever take credit for what my students achieve. It’s their talent. I just nudge them. And if they don’t have it … I nudge them and stand back and see what happens.”

In 1995 Hepburn did a residency in Hertogenbusch in the Netherlands that was critical. He was engaged with the work of Hieronymous Bosch, particularly the fact the “Bosch invented the notion of the absurd.” Elements from Bosch’s paintings started showing up in Hepburn’s’ sculptures leading him to intersect his work with two-dimensional images. He also came back enthused by the explorations of clay that were going on. There clay was not a “craft” medium, but art, as it was considered in many European cities. They had equipment that was so advanced it changed the practice. The kilns in particular were digitally activated and huge. The floors of the kiln were flush with the building floor so the kiln shelves on a cart could be wheeled in and fixed in place. That way a work could be made in the studio on the cart and pushed into the kiln, without the problems of moving the piece from one surface to another. The kiln size also allowed for large works to be made. Hepburn worked with the architect of the new Cranbrook building, Rafael Moneo, to provide the right space for these kilns. Their tall chimneys are a major feature of the building. The kilns provided the opportunity for Hepburn and his students to move into the future. The digital controls took some of the mystique out of the firing process because the results were more controlled. A little less chance was involved, though you still never knew for sure what would happen in the kilns. But Hepburn also kept the old technology around, convinced that the variables of these ovens allowed for different explorations in the making of the work.

With the kilns, Hepburn began working bigger and then explored digital thinking. Again, bigger for Hepburn often meant an accumulation of more components rather than the making of singular or monolithic forms. His commissioned piece Korea Gate for the Clayarch Gimhae Museum, South Gyeongsang, Korea, was one of the first benefactors. He said the new kilns were so fast that what would have taken weeks to fire now happened quickly. His assistant made a series of traditional celadon Korean-style ceramic vessels, some in multiples. Hepburn made only one of the pots so his touch was there, but otherwise the vessels were more anonymous and generic. This was something he often sought – the generic being a more universal symbol or icon of the ordinary. Say the words – pot, broom, gate – and you know it from having touched one, seen many.

Then he balanced groupings of these facsimiles to build a tall gate that was to go near the entrance of the major ceramics museum in Seoul. The structure was critical – a bit like building with blocks, but here providing a haptic sense of the fragility of ceramics. The hallowed history of Korean ceramics was the connector to the country, as were the objects themselves – idea and thing. There were two gates – the larger one was 17-feet tall. One could move through it. But not the smaller one, which the viewer could only see and think about how it would be to move through, providing the “perspective thing,” as Hepburn said. He explained “Getting so many pieces to fit together was really hard. Yet there was a sense of interchangeability. It was a balancing act […] the precariousness means it stays fresh. This gate was all hypothetical until it was done. I liked the risk.” These gates retained the memory of the masterworks that followed in the museum. Thinking about the piece in that context meant that Hepburn’s gates took the history forward into the digital age where resemblance summoned the experience of the original pieces like a picture of a familiar work of art on the web. Through the physical presence, or embodiment of this idea, Hepburn was representing the idea and experience. As was his wont, after the piece was installed in Seoul, Hepburn did a series of drawings where he relied solely on his memory of the gates in the space. He said that “To draw you don’t have to deal with a lot of crap like gravity and the physicality of making.”

His next important body of work concerned a very personal turmoil. Hepburn’s wife Pauline became ill around this time and they spent the next 18 months fighting her cancer. The equipment of the hospital – the banal, generic stuff like the tubes and pill vials and syringes became the parts of both his sculptures and drawings. Stethoscopes – or ears to the senses – were often present. Some of the parts were actual, others made of clay, other works were huge drawings made with his powerfully dark, expressive lines. There was fluidity to these works – the fluid of the body and the hospital intervention in that body, and the connection that fluid makes between life and death. The drawings became more and more prominent as Pauline’s life slipped away. Hepburn was as good a draftsman as he was sculptor. His feelings came through clearly. He wasn’t after understanding with them because there was no way to understand why she was leaving him. The drawings were exorcisms, the way he used his memory to flush through one of life’s most painful experiences. “The drawings had to be as beautiful as she was,” said Hepburn. And they were.

The last major series Hepburn produced at Cranbrook incorporated digital photography, language, chance and of course clay. “I was in the 2-D design department and a visiting artist was talking about 3-D topography,” he recalled. He studied the system of topography and began thinking about how to turn a letter and then a word into an object that could be arranged topographically, then transformed into a digital image and memory. He began by making the letters of clay. The letters were then arranged into words laid out in a circle on a turntable. Then the table was spun and Hepburn photographed the letters moving with a stationary digital camera that had a long exposure. The photographs captured a bit of the word, but more of the word as it disappeared in the spinning motion. The viewer saw where the letters began, but then was drawn into the experience of the word moving out of perceptual recognition. The letters pixilated and led Hepburn to make new forms, forms he said he would never make in clay. Like a video or photograph from, or of, an installation, the photo is the evidence of the experience that occurred. But time is captured elapsing. Movement in space is captured. The three-dimensional object disappears in the photo leaving a simaculum. Once solid, then ineffable, but still a remnant in image and memory. These were gorgeous pictures.

Tony Hepburn’s work was metamorphic. He explored his territory alone, one of a small group of ceramicists working in their own ways, artists who ranged across many media and merged them. Perhaps there were junctures when Hepburn wondered if the fine art establishment would finally see what he was doing. At Cranbrook that happened all the time. But often that recognition never got past the wrought iron gates. The work is as vital today as it was when he made it. Now that ceramics has become a medium and a subject that is being looked at in the fine art world, perhaps Hepburn will finally be given his niche in art history. He earned it.