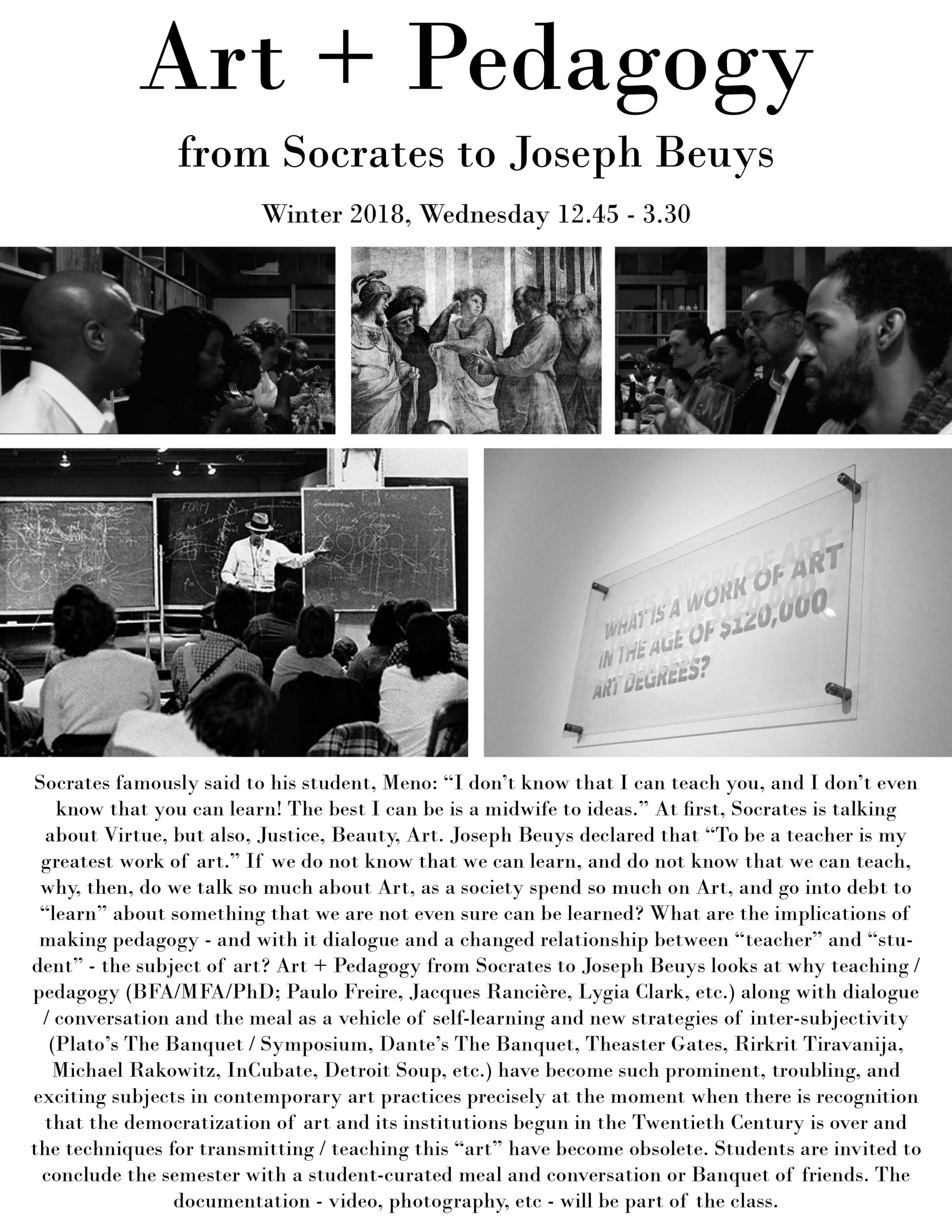

Introduction: Research / Art + Pedagogy /

or, Time in Critical Practice

Normally, things begin to pick up by week 3 or at the latest week 4, but in this case, something happened when in week 2, picking up on some tremors I had felt in week 1, I introduced earlier than planned (after a discussion with the class) Michael Asher’s post-studio crit at CalArts. (Sarah Thornton’s Seven Days in the Art World was our port of entry.2Cf. Sarah Thornton, “The Crit,” Seven Days in the Art World (New York: Norton, 2009), 41-74.) A switch had been flipped on. There was light. There was discussion. There was passion. There was anger. Frustration in abundance. Much quoting of texts. Everyone could see their situation framed and ready for discussion in front of them, as if a specimen were there awaiting vivisection. Just about everyone hated the Crit – to be capitalized henceforth – and just about everyone grasped something of the implication that if the main institution of teaching in a school of art and design, namely, the Crit, is not fit for purpose then something more profound was at fault in the very nature of what instruction / learning might be (not mean but be) in the epistemological frame of an art and design school.

The passions ignited by discussion of Asher’s post-studio crit – and not a single student had ever heard of Asher, still less his post-studio class – stunned me. I have not infrequently been in a situation when class discussion takes off and as a teacher one becomes an engaged observer trying to stay out of the way, but this went on for three weeks before I said that I would re-work the syllabus and pursue new but related pistes. - For example, Robert Irwin would enter the new iteration of the seminar.

Point 1: A main aim of the class was to consider the nature and purpose of teaching / learning as the transmission of values that constitute a field of practice, knowing that, as Plato explored in the Socratic dialogues, values and ideas die and so there is nothing inevitable or necessary about a particular set of ideas that is being currently taught.

Point 2: We read Howard Singerman’s exceptional book, Art Subjects,3Howard Singerman, Art Subjects: Making Artists in the American University (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999). on the history of the MFA in the American academy and how the MFA was explicitly never intended to become, and is not to this day, a degree connected with the ability to teach.

I have a precise memory – and notations – of what was said during these discussions, but let me start here: Students themselves must take some responsibility for the failure of Crits. I was struck by the maturity of this recognition and the quality of the observations which it provoked. Even more, however, the Crit itself was the problem. In Asher’s practice, on the other hand, students saw a whole new practice of temporality and agency: that a Crit might run for 12 or 15 hours did not frighten them but instead excited them; that the “professor” did not speak, or barely so, intrigued them, even more so as they would come to grasp that the implied practice of listening and utmost presence left students to come to their own realizations about the strength and weaknesses of their work;4I continue to see in this practice of listening and agency for the students a version of what the Lacanians of the École freudienne de Paris, … from this many students started a discussion about the role of duration in the Crit, being durationally embedded, both instructor and students, hence no outsiders joining the Crit simply to talk about their own taste or aesthetic; above all, what they got a hold of tight was the idea that the silence of the instructor in the practice of the Crit meant that the work was not there to be turned slowly into a copy of their instructor’s work or become an instance of the instructor’s taste. Here Robert Irwin joined Asher – my own deep interest in Irwin was wholly due to one of the most important CCS alums, the artist Michael E. Smith, whose work is in dialogue with Irwin’s thinking on spatiality - especially the Irwin who observed:

All the time my ideal of teaching has been to argue with people on behalf of the idea that they are responsible for their own activities, that they are really, in a sense, the question, that ultimately they are what it is they have to contribute. The most critical part of that is for them to begin developing the ability to assign their own tasks and make their own criticism in direct relation to their own needs and not in light of some abstract criteria. Because once you learn how to make your own assignments instead of relying on someone else, then you have learned the only thing you really need to get out of school, that is, you’ve learned how to learn. You’ve become your own teacher.5Robert Irwin, quoted in Lawrence Weschler, “Teaching,” Seeing is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One sees: A Life of Contemporary Artist Robert …

What a rich passage! Not the least important aspect of this reflection is the awareness that in teaching one teaches not to the thing (product or stuff) but to the person – they are what it is they have to contribute – a person who is learning to self-authorize and who in doing so places oneself in question, the most perilous of acts. As teachers we often casually forget the existential dimension involved in becoming who we are, and, even more casually, we commit the grave error of thinking that it is only the good, the successful, or the great ones whose struggles matter, whereas every single person endures their struggle toward their ideal of self.

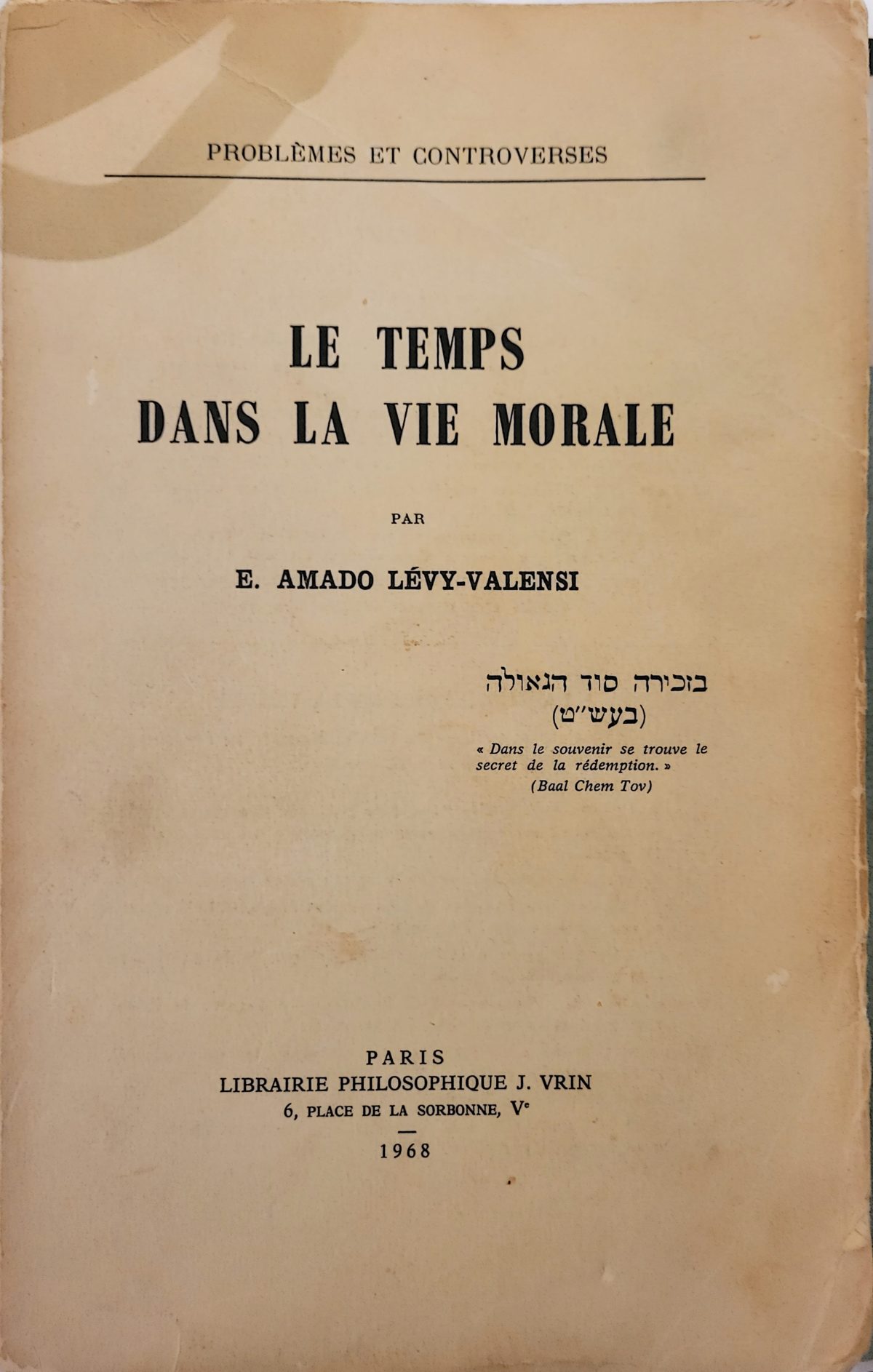

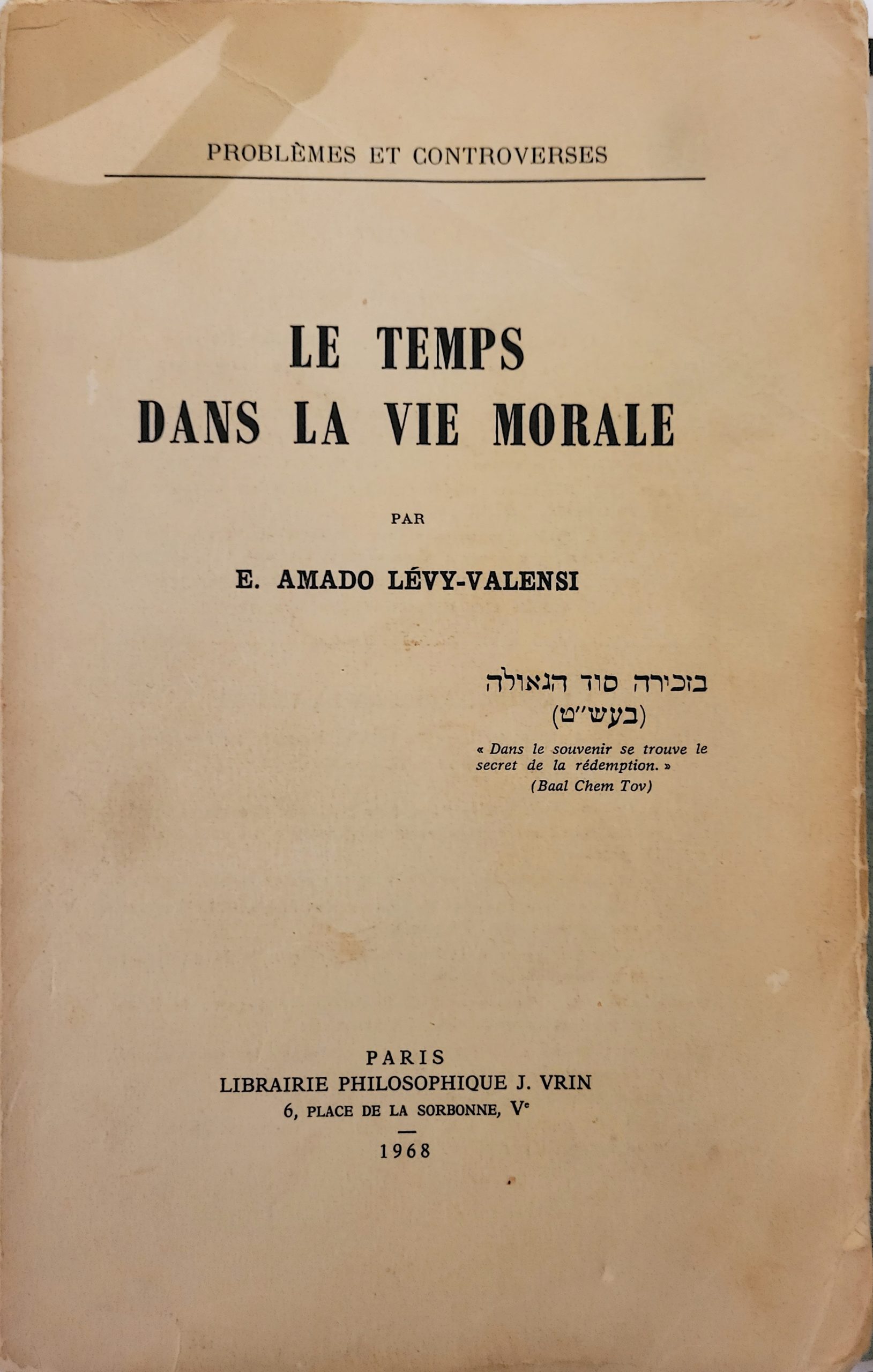

Le temps dans la vie morale, 1968. Cover of Eliane Amado Lévy-Valensi from the personal library of Michael Stone-Richards originally acquired to study the tradition of moral psychology and time in the thought of Guy Debord

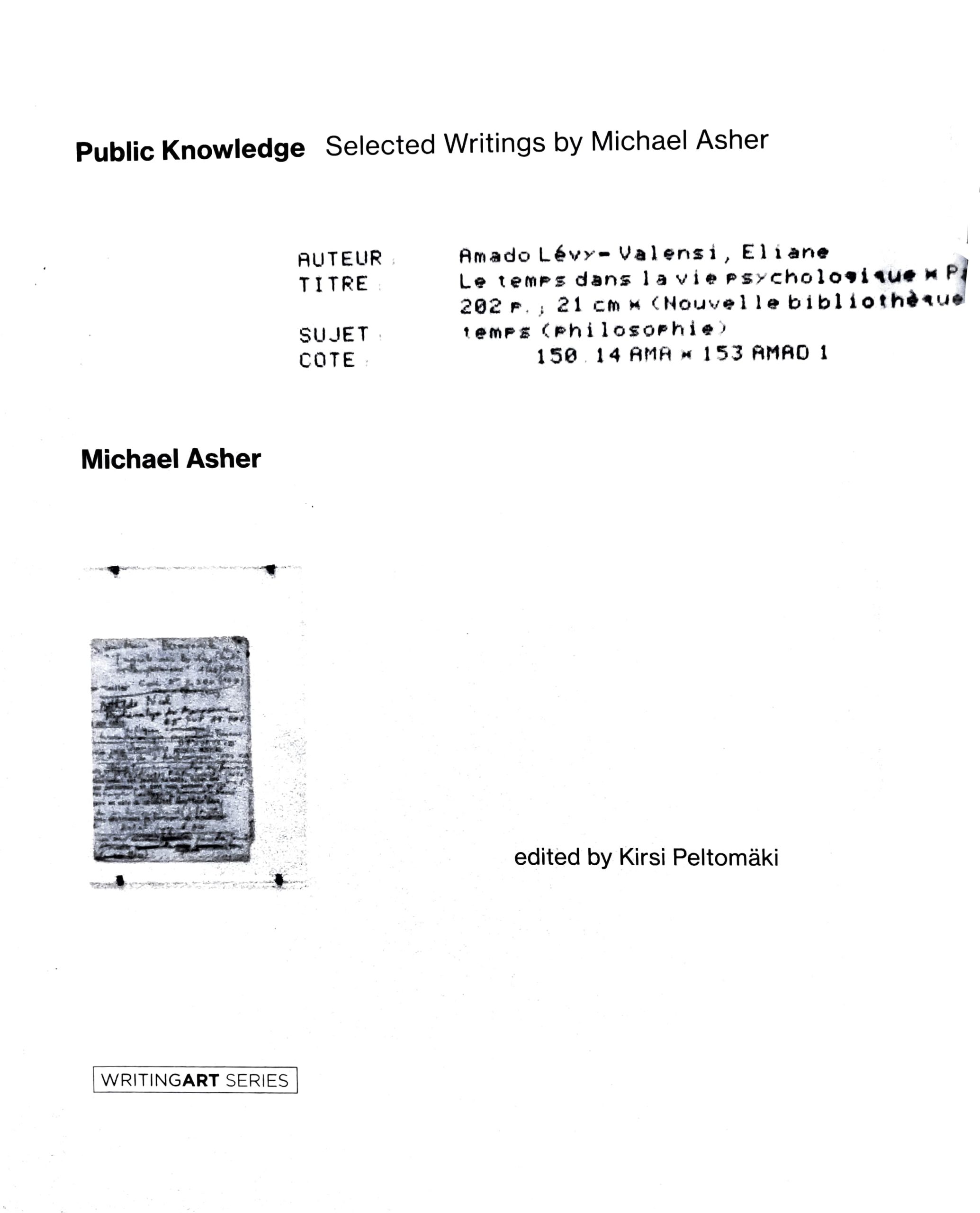

Cover of Public Knowledge: Selected Writings by Michael Asher, 2019.

The cover shows an installation detail of a work in the Centre Pompidou’s Michael Asher, 1991.

Observation 1: A key question that emerged from discussions on the Crit, a question which formulated a concept, was the following: What do we want a Crit to be: an artisanal imprinting or a critical practice? Artisanal imprinting pointed to the absorption of the instructor’s studio practice6As one student commented to the class: “There was a moment when I realized that all that I was being taught was my teacher’s studio practice!” the best version of which might be, say, a conservatory approach, whilst the idea of a critical practice, pace Asher, Irwin, but also Roland Barthes’ conception of co-creation and mothering in the space of the seminar, that is, the shared space of learning, pointed to critical practice, research, and knowledge.

Observation 2: There was a fascination with Barthes’ conception of co-creation and mothering as developed in his “To the Seminar”7Cf. Roland Barthes, “To the Seminar,” The Rustle of Language, trans. Richard Howard (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989), 332-342. … – the genre of the German lieder An die Musik (with reference also to Rilke) was discussed as also the transferential dimension in learning – from which the following question: What if the Crit as conventionally established is a refusal of co-creation? This led to an examination of the mothering aspect of Asher’s post-studio crit, that is, the space of the Crit as an envelope jointly created by all who participate.

The term research has come to mean many things within the framework of Critical Studies, that is, the variety of Critical Theory developed within the art school responding to the epistemological and methodological challenges posed by the cultural triumph of the twentieth-century avant-garde. (The negation of classical Critical Theory, for example, is made possible by and is a reflection upon the practice of negation in the avant-garde, just as the avant-garde refusal of genres is made materially equivalent to the refusal of the departmentalization of knowledge on the part of Critical Theory.8Cf. Herbert Marcuse and Bryan Magee, “Marcuse and the Frankfurt School: Dialogue with Herbert Marcuse,” in Bryan Magee, Men of Ideas: Some … ) Artist research, artistic research, research-driven design, and more. The arrival of the PhD in Art testifies to the expansion of research even as we are not in steady agreement about its nature and practice (something made clear by NASAD documents9On the question of the PhD / terminal degrees in the Arts, see the very illuminating NASAD Policy Analysis Paper, “Thinking about Terminal … ), but it is clear, however, that the development of the PhD in Art is a direct function of the fact that the MFA was never meant to be a teaching degree and the art and design school is caught in an incoherence between those who want to teach a studio practice (more or less well)10And the Conservatory is the highest form of this practice – the Conservatory in music, in acting, etc. Might it be possible to think of Black … and those for whom college-level education requires something more rigorous than savoir-faire as well as something more epistemologically and ethically urgent. Here it is worth quoting Asher when he observes with a certain simplicity – and, I believe, humility – that

One of the few reasons to have a program in the studio arts is to acquire knowledge about the history of culture and learn its production as a practice for social transformation through the problematizing of representation.11Michael Asher, “Notes on professional degrees in studio art” (ca. 1988), in Public Knowledge: Selected Writings by Michael Asher, ed. Kirsi …

Spontaneous movement like this…listen…!

Here the artist has formulated what is, in effect, the guiding principle of late modern art education as a general principle of education, that is, “a model of general education. Not in the sense of liberal arts education reform. But that art could be the key to a generalized education […] not just to the work of art, but to the world.”12Stephan Pascher, speaking with Michael Asher, “Conversation with Stephan Pascher on Teaching” (2005), in Public Knowledge, 235. This is the Critical Studies of the art school becoming a Critical Practice, a knowledge in contact with, bearing upon the world. This view of practice as contact with the world is fundamentally Aristotelian, but the late modern tradition, at least as it bears upon art as a general principle of education, as in all matters to do with modern art, is mediated by Kant who, in his anthropology, observed that

All cultural progress, by means of which the human being advances his education, has the goal of applying this acquired knowledge and skill [that is, practice, MSR] for the world’s use.13For the world’s use, that is, practice – if it is not simply the production of stuff – must be reflexive. The production of things, to be … But the most important object in the world to which he can apply them is the human being: because the human being is his own final end. Therefore to know the human being according to his species as an earthly being endowed with reason especially deserves to be called knowledge of the world [emphasis in original], even though he constitutes only one part of the world.14Immanuel Kant, “Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View,” in Anthropology, History, and Education, ed. Günther Zöller and Robert B. Louden …

Kant goes on to clarify his sense of pragmatic anthropology by saying such knowledge of the world is only called pragmatic “when it contains knowledge of the human being as a citizen of the world.”15Kant, “Anthropology,” 231-232. Emphasis in original. In this respect Kant’s pragmatic knowledge is here a transition between the classical Aristotelian view of practice and the modern view of praxis as formulated by Marx and re-transmitted by Althusser. It is also fundamentally the basis for any critical account of practice as central to the modes of contemporary art as critical engagement with world-making and demystification of representations, that is, the ideologies masked as realities which serve to distort the relations to the world. Eventually this mode of thinking about practice and pedagogy in the art and design school would become formulated using the established language of the PhD, namely, that document of research that makes a contribution to knowledge, or, in the language of Critical Practice, the production of knowledge since there must always be awareness of the material conditions of knowledge-production. (It is, of course, by no means clear that Asher would have been invested in the idea of the PhD in Art, and certainly not as a qualifying degree for teaching.)

Yes, research is the production of knowledge. It is also the examination of the conditions of possibility of the production of knowledge – or representation(s), as Michael Asher rightly observed in a manner typical of his generation of artist-thinkers – but above all, since the inception of the Socratic inquiry (the putting of things and self into question) research, which is fundamentally a quest, has been the encounter with spontaneity, since the knowledge that matters is always the one that, unbidden, surprises me, threatens to change me from my existing idea of myself. (Education is this journey away from the self, and as the “Allegory of the Cave” shows, such learning hurts.16It does not hurt because some person in authority wants to abuse their authority, impose their prefabricated knowledge on a young mind in the name of …

… Spontaneous movement like this …listen …

That search, re-search, quest required of its author sustained acts of attention and sorting of attention and kinds of memories. That quest, some 7, 200 pages later, encompassed music, art, architecture, manners, dress, social history – there is no critical account of class more precise than that on display in La Recherche - politics, music, philosophy, and resulted in, and was sustained by, a vast architecture of knowledge as a practice of reading through which emerges a practice of living, a practice of deep modes of attention where attention is the moment of contact with life, a social practice as critical practice.17Cf. “Aporias of Attention,” forthcoming in Michael Stone-Richards, Care of the City (Berlin: Sternberg Press). The monk in Kentucky, Robert Merton, like Robert Irwin, saw this clearly when he could say with earned simplicity: education bears on the person, and learning - that is, the training of attention18Paul Celan: “ ‘Attention’, if you allow me a quote from Malebranche via Walter Benjamin’s essay on Kafka, ‘attention is the natural prayer … - is learning to live:

Life consists in learning to live one’s own, spontaneous, freewheeling: to do this one must recognize what is one’s own – be familiar and at home with oneself. This means basically learning who one is, and learning what one has to offer the contemporary world, and then learning how to make that offering valid.

The purpose of education is to show a person how to define himself authentically and spontaneously in relation to his world – not to impose a prefabricated definition of the world.19Robert Merton, “Learning to Live,” Love and Living, ed. Brother Patrick Hart (New York: Harcourt, 1979), 3.

As all aspects of college-level education come under economic and demographic pressures, it will become increasingly clear that the current pedagogical models are in need of deep revision, even if one believes in the vocational role of college education. The most sophisticated technology will continue to displace people; indeed, technology is being devised which can design technology to enable new kinds of replication without the intervention of people. It is already clear that education in art and design needs a new vocabulary. This moment is an opportunity. It is existential.

From my arrival at CCS I have taught research to artists and writers, but I have never reduced research to academic research as typically understood in the Humanities since I have never taken that as the only or even dominant model of research, hence as I came to explore the history behind the term Critical Studies, as offering alternative models of research and pedagogy, namely, Critical Studies as not simply a portmanteau term – like liberal arts – but rather a set of epistemological strategies, something developed within the culture of art and design schools – whence the separate departments of Visual and Critical Studies from Liberal Arts in many of the great schools - something that has emerged with its distinctive language, concepts, and vocabulary, its journals and conferences, but above all its practices which have a genealogy, and as a result I have come, over a number of years, to move my own pedagogical practice into teaching seminars in Critical Practice the main concerns of which have been questions bearing on transmission.20My own thinking on the question of transmission has long been shaped by Wladimir Granoff, Filiations: L’avenir du complexe d’Oedipe (Paris: … This emphasis on transmission means nothing is taken for granted, nothing is given, there is no abstract idea of what is good in teaching or learning, no notion that it is a terrible thing if students do not share my sense of what is valuable – but rather that there is a sense of wider fragility in culture and this fragility bears down on the classroom as a principle medium of transmission in culture – hence the concern with seminars and reflections bearing on the transmission of values, the fragile nature of sociality, Care, waste and violence in the modern world, but above all what does it mean to be involved in this queer business of teaching and learning art (and its histories and forms of display that can no longer be wholly contained within art history or even cultural history as traditionally understood), for it is a very strange thing indeed and no amount of professionalization can entirely rid one of the sense of the strangeness of teaching and learning art in an academic or art school context – the two contexts are not identical.21Cf. the “Conversation” between Michael Craig-Martin and John Baldessari in Art School (Propositions for the 21st Century), ed. Steven Henry … It might even be said that in these seminars collectively we have tried to return something of the poetry of art through the process of learning about its possible transmission and failures. The following interventions bear testimony to this attempt to think art as lived experience in terms of Critical Practice, a studio of thought and embodied articulation, where practice has the sense found in Aristotle, Marx, and Althusser but also Simone Weil: not the production of stuff but the reflexive actions by which selves are transformed in relation to the world, practice as “the active contact with the real which is distinctive to the human.”22Louis Althusser, «Qu’est-ce que la pratique?» Initiation à la philosophie pour les non-philosophes (Paris : PUF, 2014), 163. Emphasis in … Certain students were impacted by the idea of conversation as a medium: thus Shannon Morales-Coccina writes in dialogue form of the Crit; Monique Homan, Mollyanne McLaughlin, and Anisa Rakaj record themselves in conversation practicing Critical Theory; another section is devoted to students’ own proposals for what a transformed pedagogy might be with Caleb Gess, Christopher Holdstock, and Brendan Roarty, sharing their “Proposal for Redefining Art School,” and Alexander Knepley reflecting on a “(Non)Ideal Pedagogy,” and Gabriella Fossano sharing her insights (and demands) “On the Design of an Art School.” CCS alum Grant Czuj reflects upon his time and practice in Painting at Yale. (Here I should point out that all these students were or are students in the Minor in Critical Theory.) One item that came up often in our discussion was the role of contemplative or mindful practices as a mark of a new approach to pedagogy and the demand that practices of mindfulness no longer be regarded as an extra, a nice thing or luxury but as an essential to the health of students, as, indeed, a life-practice. The group BFA/MFA/PhD has been exploring this for some time,23Cf. Susan Jahoda and Caroline Woolard, Making and Being: Embodiment, Collaboration, and Circulation in the Visual Arts (New York: Pioneer Works … but Molly Beauregard has also been exploring this question of mindfulness at CCS over 10 years in her class on Consciousness, the results of which are now available in a book from SUNY Press.24Cf. Molly Beauregard, Tuning the Student Mind: A Journey in Consciousness-Centered Education (Albany: SUNY, 2020). Here Beauregard shares with us a reflection on the development of her practice at CCS which has been deeply influential on the student body – no class fills more quickly at CCS than Beauregard’s class on Consciousness and we have no doubt that in a thoughtful, student-centered curriculum, practices of mindfulness would be offered as part of the Freshman experience as a form of practice in health.

As I am making a final review of this text, the tennis player Naomi Osaka is in the news for withdrawing from the French Open on grounds of mental health. Her action has triggered a long overdue debate on mental health amongst elite athletes, but one may see this debate as not primarily a debate about elite athletes but as part-and-parcel of a larger societal conversation on self-care and the degree to which the obligations of the workplace do not abrogate the needs of care. (Selma James and Sylvia Federici have long made this argument in the context of the politics of Care.) The “elite athlete” is simply the mechanism for triggering attention for a perceived need. The work of Molly Beauregard and BFA/MFA/PhD is part of a similar conversation in the art + design school arguing for self-care in the curriculum and practice of pedagogy and not simply in an office secreted away with college nurses or counselors to which one makes retreat when it is often too late. What if, following BFA/MFA/PhD and Beauregard, practices of mindfulness were made part of the curriculum from Freshman Year for the eminently practical reason that such practices will lead to more balanced and effective students? Indeed, there is much research to support the view that a broader practice of care toward students would lead to improved pedagogical and personal developments.25Cf. David Kirp, “Community Colleges should be more than just Free,” The New York Times, May 25, 2012. …

This section on Critical Practice closes with a set of reflections on the aporias inherent to late-modern design which I delivered in a panel discussion at the annual AICAD conference held at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 2018.

References