Lun*na Menoh

Lun*na Menoh, Lun*na performing/conducting Maurice Ravel’s Bolero at the Velaslavasay Panorama, Los Angeles, 2016.

Photo: Takuya Ichinose

Lun*na Menoh’s focus is on clothing. Not only what one wears, but also the history of wearing clothing and what that means to culture, society, finances, politics, and aesthetics. At times, it seems all roads lead to the discussion of clothing, and how that takes part in not only our lives, but reverberates like an echo after the work is presented. Menoh works in painting, sculpture, and sound, all related to clothing. I use the word clothing because I feel “fashion” is too limited in this sense. Fashion does take place in apparel, but it’s only one aspect of that world. Menoh explores the entire world of what it means to make and wear clothing: as something to see, either as a sculpture, painting, or just the clothes themselves.

Menoh is fascinated with the trade that produces and manufactures clothing as well as the structure of the industry and the tools that are used for production. She is interested in the process of laundering, or to be exact, companies that specify their business on getting rid of a dirty collar stain on a men’s, button-down, white shirt. Menoh’s approach is to expose the collar, and therefore spotlight the worker, who must keep up an appearance in front of his co-workers and people outside the factory/office. Menoh’s obsession is to collect these dirty shirt collars. She creates wearable sculptures out of them. Using the filthy collar as a source for making objects such as tea cups, bedding material, furniture, boom-boxes, as well as wedding dresses with long trails. She also paints portraits of well-known musicians, such as David Bowie, Prince, Patti Smith (from the cover of the album Horses, 1975), The Velvet Underground and, of course, The Beatles, in these dirty collars.

The pop musician, like the office worker, must keep up their appearance. Menoh’s painting of David Bowie from the Station to Station era (1976) is iconic, but painting his white collar as sweat-stained gives the image a human touch: a commentary on work, and how every person makes by-products of their daily toil, whether it be in the factory, an office job, or on stage. The inner collar will expose one as a worker who sweats for their job, either due to the physical work or the intensity to produce one’s work. The question is how has the theme or the process of making clothes become music?

Italian Futurist painter, composer, and builder of experimental music instruments, Luigi Russolo, in his 1913 essay “The Art of Noises” (L’arte dei Rumori) comments that the modern sound, otherwise known as “noise,” came from the 19th century when machines were first used. Before that, it was the sound of nature or crowds, for instance, rainstorms, waterfalls, and people chatting. Russolo encouraged the artist and listener to explore the (then) modern city landscape for inspiration, or even better yet, the workplace. Due to machinery, new sounds were being made that fully expressed the “now” of that particular time and place.

Sewing machines are noisy. Imagine a factory full of sewing machines, and they are all on at the same time. Noise or ambient music? Or both? Menoh is very aware of Russolo and loves what she imagines is the industrial sound of the 19th century turning into the 20th. The sewing machine is the first machinery that was used in a family household, before the telephone, the fridge, or the washing machine. The sound of the sewing machine in the house was probably the first noisy object in the domestic landscape. Most likely, it was the mother sewing, making clothes for her children, or perhaps fixing a husband’s jacket or pants. The world judges a person by their appearance, and the wife in a family household had the responsibility to keep up the family’s image. Once the sewing machine became part of the family home, there was no turning back. Machinistic technology held a permanent place in the home.

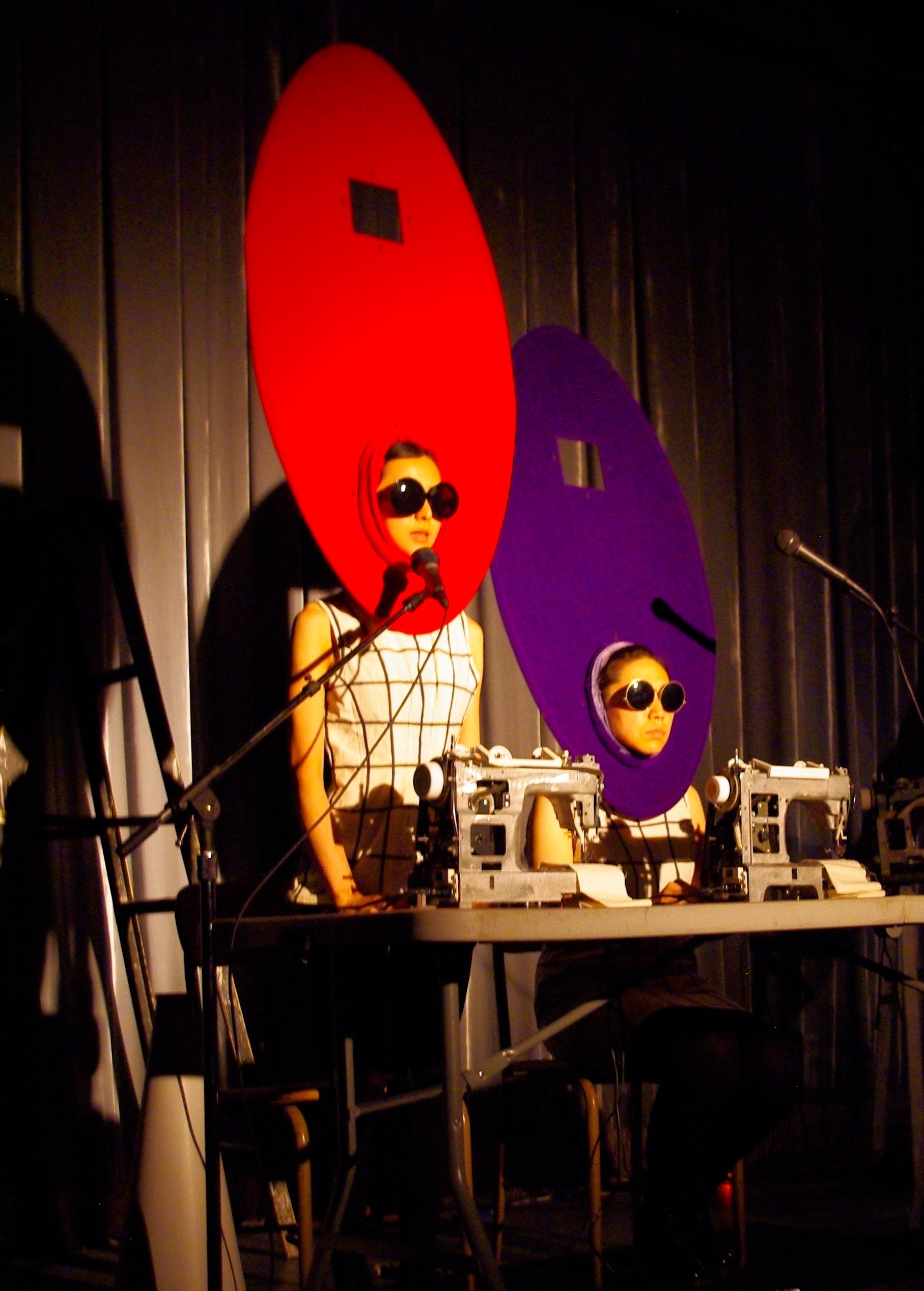

Menoh started off her “music” career by being a member of an electro-duo Seksu Roba, which in Japanese means sex donkey. After the band had split up, Menoh formed a group called Jean Paul Yamamoto. Menoh’s concerts were always theatrical spectacles, but Jean Paul Yamamoto was her first venture as a musician who had total control of the costuming and the music. Electro-funk-rock-noise was Menoh’s take on the world around her. “Starbucks Hyper-Bitch” is a stand-out song.

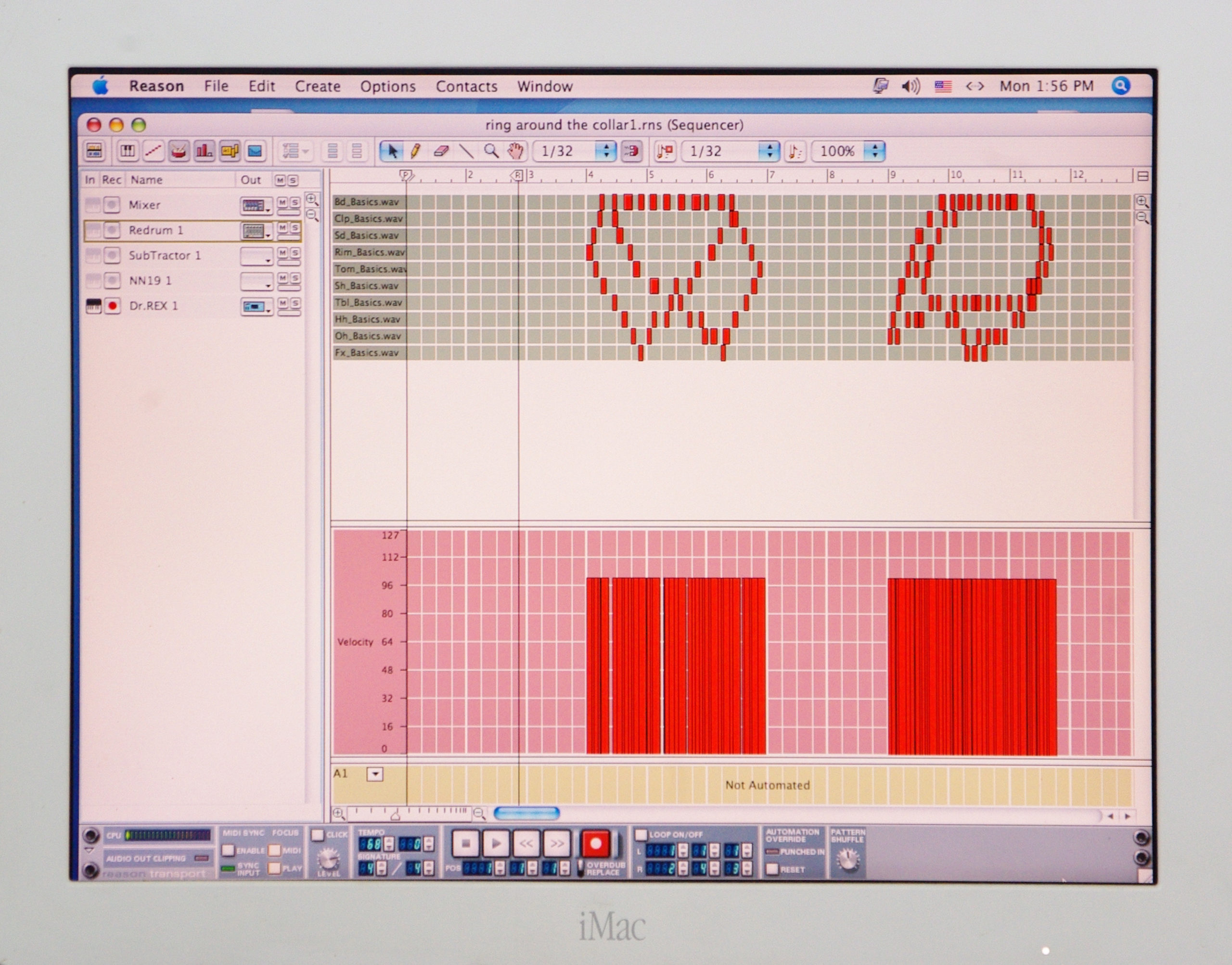

Soon after Seksu Roba and Jean Paul Yamamoto, she developed a musical project, Les Sewing Sisters, which only deals with the subject matter of clothing, or sewing. She wanted to make the performance and music more extreme. The primary instrument for Les Sewing Sisters is the sewing machine. It is filtered through a MIDI synthesizer process, looping, as well as recording various sewing machines in the fashion of the eccentric British record producer Joe Meek. In the late 1950s to the mid-1960s, Meek had one of the first home studios, where he built all his recording instruments by hand. He invented or used out-of-the-ordinary practices to get the sound he wanted, such as recording the toilet flushing and then running the tape backward. In the same manner, Menoh records her various collections of sewing machines in unusual locations, for instance, in the washing machine, which gives it an eerie echo.

To make music by sewing machine has become an obsession for Menoh. When listening to Maurice Ravel’s (1875–1937) Bolero she discovered it to be a work not of romantic passion, as it is often displayed in the popular media, but music inspired by the noise and pace of the factory in the middle of the Industrial Age. Ravel’s father, Pierre-Joseph Ravel, was a civil engineer and inventor. He was a visionary in the car industry, and built a race car that went up to 3.7 mph (in the 19th century). Ironically enough, with respect to Menoh and her interests, he also invented the machine for sewing paper bags. Ravel Sr. encouraged his son to study music, and Bolero is clearly influenced by the rhythmic sounds of machines in a factory.

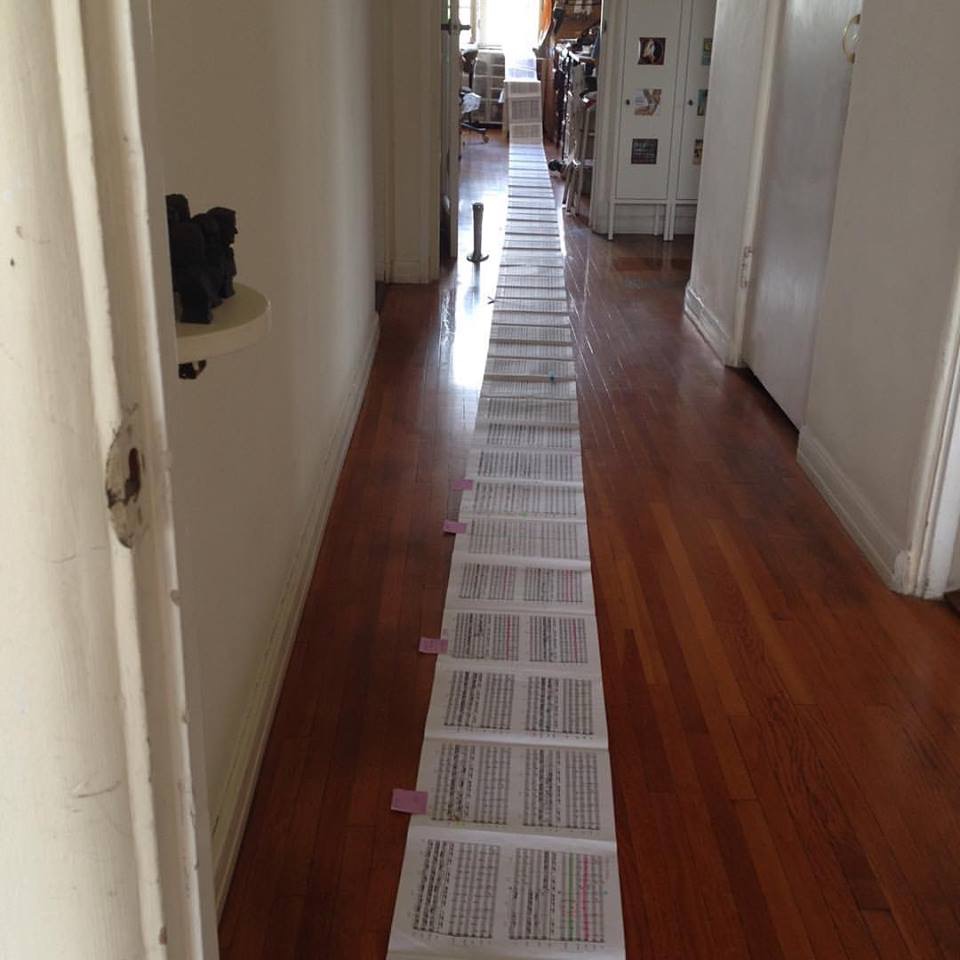

Menoh decided to do a version of Bolero, but with the sounds coming from a sewing machine. From the Los Angeles downtown library, she checked out Ravel’s sixty-four-page-long score. As a child, like other kids in Japan, she was encouraged by her school and parents to take up the piano. Through piano, she learned the basics of the keyboard, but also the ability to read a score off the page. She took each sound of the sewing machine and transported it into actual instruments of the orchestra. For instance, if there is a flute sound in the score, she found that on the sewing machine. She obtained some sound files from a friend who collects various sewing machines, and made her own recordings of machine noises in various areas of her studio and bathroom. She recorded sewing machine noise in the washing machine, the shower, and other parts of the house and building. She then transcribed each sound to a musical note. This process alone took eight months. With the score on hand, she then did the orchestration with the various sewing machine noises.

What one may think a “kooky” version of Bolero is actually a very realistic version, eighteen minutes long, which is the original length of Ravel’s score. It has been reported that Ravel was upset that the conductor and orchestration were playing Bolero too fast. If Ravel had the opportunity, I think he would have admired Menoh’s orchestration of his piece. In essence, she brought the work back home. To the factory.

It seems now she has touched on all the senses of making and dealing with clothing—even smell (while working on the dirty collars, she wears a surgical mask to hide the smell of the stained cloth.) The sound that emanates from sewing machines exposes the role of manufacturing in clothing production. It is not uncommon to be in a room with lots of sewing machines working simultaneously, which one can either make into something loud and irritable or, with a sense of Zen-like inner emotions, make ambient.

Sound or music–or both–is not separated from the visuals or other mediums that Menoh works within. Richard Wagner used the term Gesamtkunstwerk, which means total work of art as embodied in a synthesis of the arts. For Wagner, it meant to unify all works of art for the theater (opera). For Menoh, the foundation is the subject matter of clothing, and using that as a platform, she has built her paintings, sculptures, theater, as well as music, in that framework. One can take just the paintings or the sculptures — because they do stand alone or apart from the other works, but the truth is there is a connection between all the mediums that Menoh operates in, and the sound and vision of clothing is her vision of the world.

Lun*na Menoh, Lun*na performing/conducting Maurice Ravel’s Bolero at The Velaslavasay Panorama, Los Angeles, 2016. Photo: Christian Tants

Lun*na Menoh, the full orchestra score of Maurice Ravel’s Bolero, Los Angeles, 2016. Photo : Lun*na Menoh