All works by Addie Langford courtesy of the artist and Hill Gallery, Birmingham.

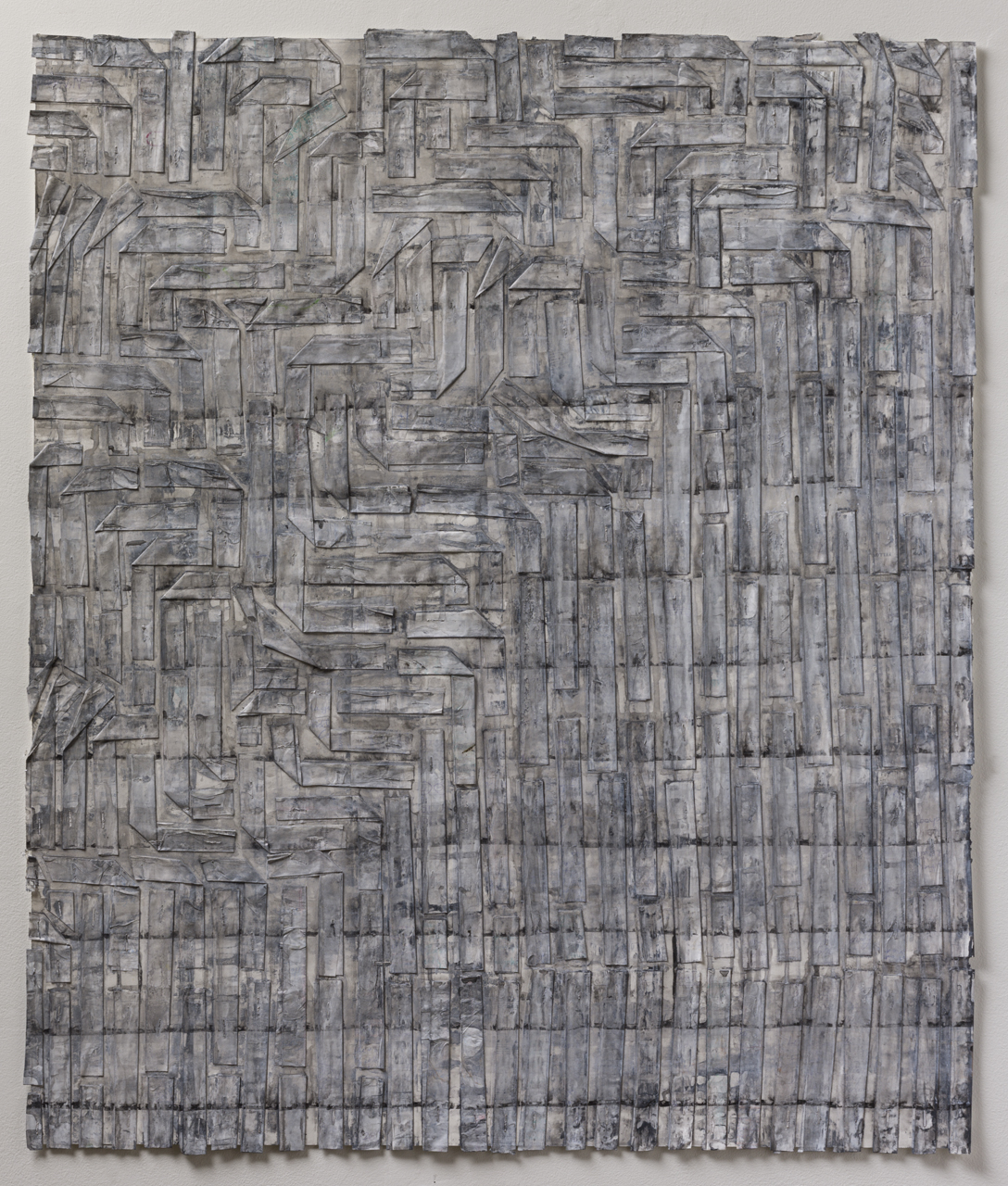

Gray: Creosote/Yellow, 2014. 25 h x 21 w

Acrylic, ink, collage, and mixed media on gessoed paper mounted on linen.

Photograph by Tim Thayer.

Whoever looks for the key to a text ordinarily finds a body,” writes philosopher Jacques Rancière, in his project tracing the poetic utterance to political subjectivity.1Jacques Rancière, The Flesh of Words: The Politics of Writing (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2004), 42.Bodies lie beneath letters, inside letters, and symbols hollow out be filled by sensory organs, memories, and specters. Evident to Rancière, text, and its practices of reading and writing, continuously performs and becomes body. A process of excavating flesh from a ruse-like strata of symbols, “the text is already of the body, the fabricated object is already of a language that beats meaning.”2Ibid., 81. Citing the language of religious ritual, the word is exceeded by the rhythms created through the convergence of documentation and performative score. Historiography turns to choreography, where the slumbering body of the past is doubled by its body-to-be, awoken towards futurity. Recitation and reception, these events of encounter are acts that unearth bodies, so we can hold them with and as our own. Bowing heads, swiveling hips, arms swinging with soft sighs, we prod our materials to unearth these yet unseen, unheard bodies dormant inside, waiting to take a leap.

I travel to this somewhat obscure moment in Rancière upon my first encounter with Addie Langford’s The Gray Series, a group of complex, wholistic, and dense works - collaged, painted, woven. Large and intricate, each piece’s palate and texture produce a sense of history discerned through acts of making and dwelling. Stratified layers across surface and depth create an organic play of marks-lines, grids, and rhythmic repetition. Like ancient papyrus, their surfaces vibrate from behind, keeping within them a key that asks to be deciphered and mulled over. They have been labored over, compressed, and felt. The materiality of the work alludes to a narrative of working: through, within, upon.

Each piece resonates a slightly different mood and tone through its visual rhythm. Woven patterns read as a commitment to a particular action, a way of moving, and through their repetitions the body is directed, oriented, and invested. With repetition the body begins to take shape. Enter the painting and we find a body, dancing against image, gesture, texture, materiality, architecture, surface. Reception in this sense could be thought as a bodying forth, experienced through the pulls and compressions within the environs proposed by a piece, conditions within which it remains. Differentiating between the work (of literature) and the text (following the pathways of discourse) Roland Barthes writes that where the text is held in language, “the work can be held in the hand.”3Roland Barthes, Image – Music – Text (New York: Hill and Wang, 1977), 157.

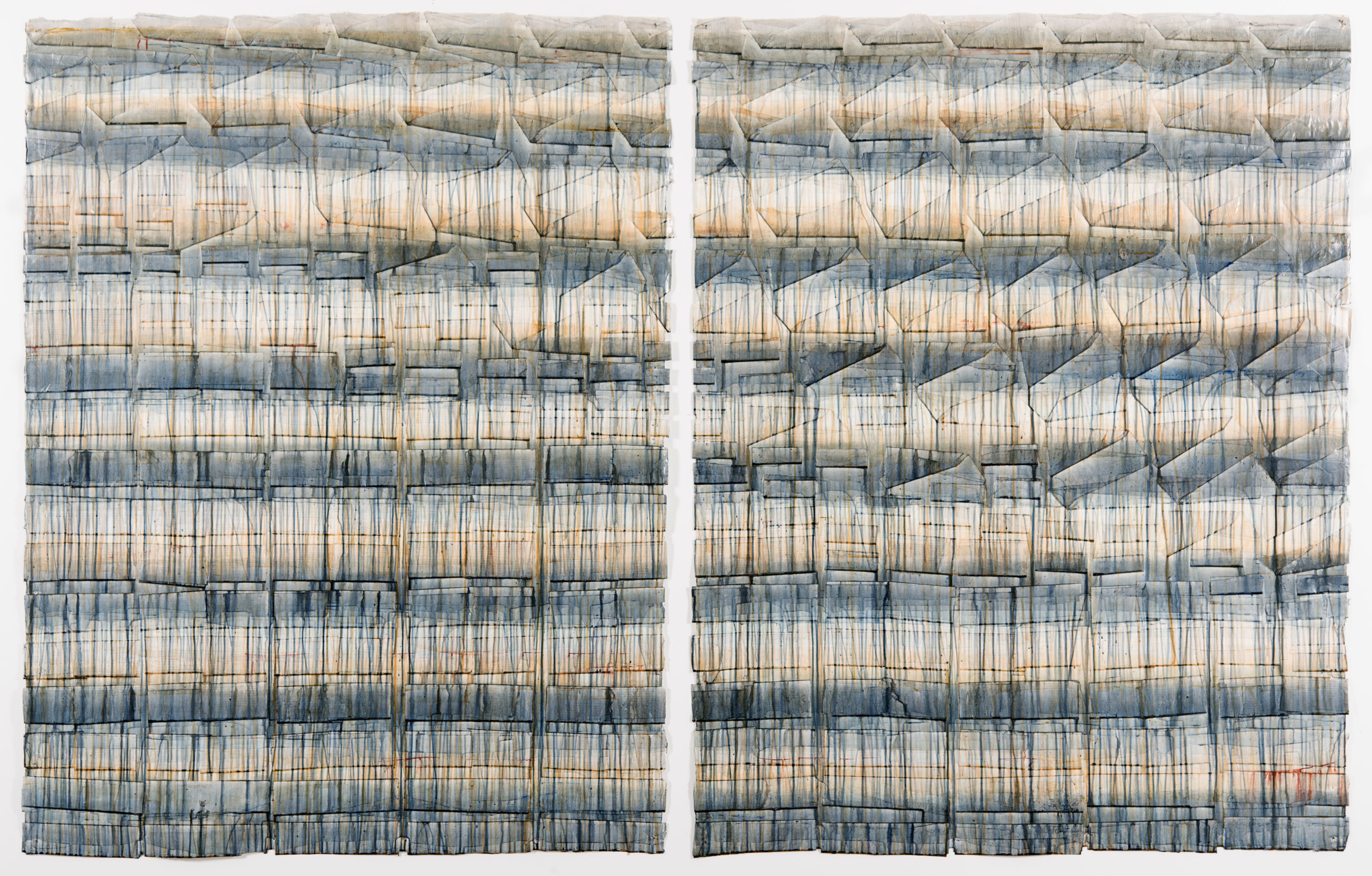

Gray: Black/Pink, 2013. 29 h x 35.5 w

Acrylic, ink, collage, and mixed media on gessoed paper.

Private collection. Photograph by Tim Thayer.

Many works in the series incorporate drips that belie a sense of gravity and weight, but not in a top-down sense. This gravity is felt through the rhythmic fall of one foot in front of the other, a cadence of projecting bodies forward. Langford’s gravity becomes material, where wash and color produce a tone of weighted-ness, pushing the eye past the surface to its underside, past the terrestrial to the subterranean. Color and wash seep into the density of paper and cloth, burying themselves inside. Drips remain as evidence. This is a body, her body. Gray: Ophelia (2011), a slow sinking. She hovers into the depths. Of dreams, desire, the subconscious, a poetic embrace within the space of loss.

Each piece in Langford’s Gray Series presents a version of stratification, like a window allowing a glimpse into a varied and deliberate process of material accumulation and compression. Haptic, the eye that touches, as Merleau-Ponty would say, this encounter is felt through the breast, the belly, the gut. Vibratory, horizontal stratifications produce rhythmic variations, a sonic score. Like heart beats of the earth, a seismic étude. Hung on the wall, a painted collage might infer Kiefer-like remnants of a scene, as with Gray: Black/Pink (2013), but viewing quickly turns into an act of dwelling within the work, displacing a sense of top-down gravity. The piece swells, it disperses its rhythm back into the room, sonically off-gassing… off-sounding.

As strata, the work moves in two primary directions: across the horizon and dripping down. Although some, such as Gray: Cream/Gray (2013), incorporate a third, puckering, crumpling outward to conjure images of the pleated tactile resilience of kumo shibori dying techniques. The image takes a turn towards materiality, felt more than seen, and so increases the urge to take a bite. Like a chocolate layered cake, texture and gait ignite my compulsion, caloric and metabolic, to take a bite. Not just to nosh across chocolaty sweetness, but to get inside its depth, to work one’s way through and be spat out on the other side. The chocolate cake image gives way to a burrowing frenzy, of kneading of garden soil and griming fingernail sediment. Pungent scent of earth, deep dirt.

These two means of intake, two versions of bodily desires, sustains a tension in the work. One is for walking; one for digesting.

Gray: Ophelia, 2011. 45 h x 52 w

Gouache and ink on paper mounted on linen.

Photograph by Tim Thayer.

Gray: Black Spoon/Tan, 2014. 72.5 h x 60.5 w

Acrylic, ink, collage, and mixed media on gessoed paper mounted on silk.

Photograph by Tim Thayer.

The room engulfs me. What room? In this case Addie Langford’s studio. A large white rectangle whose ceilings vault with a height comparable to its width and depth. Part cube, part living room, this is an architecture whose corners and underside teem with pockets of inertia and memory. Within this space, daily acts of doing make themselves visible.

It is fitting that Langford’s most recent series of paintings incorporate rough, sometimes campy, upholstery fabric as canvas backdrops. An architecture of domesticity emerges through abstract geometries of cross-hatched lines and diagonals. Thick painterly strokes, dripping down from the wall plane, become structural supports for textile and its feminized practice of weaving, not dissimilar to other domestic forms of aesthetic labor such as quilting, sewing, folding, cooking. Here she mixes materials and binds them together-a labor of adhesion, arms wrapped around shoulders, ontological glue that holds, nurtures, absorbs.

Her domestic intervention turns collage towards the familiar surface of the kitchen counter, littered with to-do lists, marks and detritus of mundane measure. The things one is supposed to do versus the things one wants to do. Each piece’s surface is brined, washed, dripped upon, and cured. Like skin, Gray: Black/Spoon/Tan (2014) bravely asserts a protective fortress, a shimmering shell, an impenetrable threshold. The artist is deviant, the path a deviation ripe with nostalgia. We turn to look back, and this looking casts yet another weave, curving towards departure. Here, the work doubles as a cartographic map turned filing system, a receptacle of time and habit and sublimations. Dark, heavy, dripping, perhaps a wound. Fleshly pink hovers - these are also ancestral bodies.

Gray: Paynes/Creosote, 2013. 15 h x 19 w

Acrylic, ink, collage, and mixed media on gessoed paper mounted on linen.

Photograph by Tim Thayer.

Of gesture

Roland Barthes discusses the artist’s gesture in the work of Cy Twombly. Through the convergence of pulsation and expenditure, gesture depicts a line of action made by the articulating body. The painting persists as a record of progressive actions and idiosyncratic variations. The artist’s body echoes as mark refers to touch refers to gesture. Presence through trace. Gesture connects us to the social as a lexicon of physicalized language, but also to the unintelligible, the unsaid, the un-thought or even fully formed. Feeling enters the room, or perhaps the room itself is structured by feeling, for, as Sara Ahmed notes, “bodies do not dwell in spaces that are exterior but rather are shaped by their dwellings and take shape by dwelling.”4Sara Ahmed, Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006), 9. From this point of entry, we might bypass the eye to the touch, the hand to the heart, the head to the belly. Here, we live in a room populated by intangible particles-memories, dreams, fears, the unconscious.

Seated in the studio, Gray: Paynes/Creosote (2013) props against the wall second to my right. Scores of collaged strips of woven paper. Their edges depict yet another layer of strata, between the wall and the page and the painting, pressing repeatedly until space is silenced and taken up by the consistency of deep browns and hues of earth. Their arrangement is geometric, ordered, and architectural though undulating, reminding me of a rammed earth temple. But, rather than depicting the act of construction, the piece settles and turns toward the precipice of erosion. Paradoxically the walls of the house morph and lumber through a labored process of drawing the earth up, pulling clay out of its slumber, and demarcating an in-between space we can inhabit. A scent lingers. It is cool and slightly moist.

Gray: Drifts/GT Blue/Gray, 2014. 36 h x 32 w

Acrylic, ink, collage, and mixed media on gessoed paper mounted on linen.

Collection of the artist. Photograph by Tim Thayer.

Gray: White/Blue/Orange, 2013. 74 h x 114 w

Acrylic, ink, collage, and mixed media on gessoed paper mounted on linen.

Photo courtesy of N’namdi Contemporary, Miami.

Of furniture

Mounted on linens, I’m reminded of my comforts. Textiles offer a worn upholstery, nodding to an imaginary neutral, domestic background. The décor of this dwelling gives the witnessing body a chair to sit upon, a couch for rest, a counter to lean against, a window to take in the view. Domestic textures, reminiscent of Eric Satie’s furniture music, tried and failed, but proves we cannot make music unnoticed as furniture, or at least he couldn’t. if the body is always found in the work, this body is not asking to go unnoticed, ignored, or feign muteness. Resting into the labor of viewing emits its own creaks and squeaks. As Martha Graham famously proclaimed, “The body never lies.”

Perhaps not a home, but a closet, where we keep hidden our deepest pains, traumas, mysteries, dreams and hopes. Compressing arms, legs, fascia, organs, heart center, and intellectual muscle in order to fit into the tightness of a space is not a mode of doing but of surviving. From the sanctuary of the closet creative acts offer an exercise in exposing our fragmented narratives to the world. From private to public; closet to pavilion. With each utterance the body is momentarily relieved of its Atlas-esque carriage. Firm fingers knead out burdened trapezius muscles running across shoulder gait. Shrug and shudder.

Gray: Cream/Gray, 2013. 21 h x 26.5 w

Acrylic, ink, collage, and mixed media on gessoed paper.

Private collection. Photograph by Tim Thayer.

Of time

Gray: Creosote/Brown/Blue, 2014. 25.5 h x 21 w

Acrylic, ink, collage, and mixed media on gessoed paper mounted on wool.

Private collection. Photograph by Tim Thayer.

Of coupling

Feminist philosopher Luce Irigaray reminds us that nature is not one, but two. The patriarchal centrism of discourse privileges the male subject, made evident even in the simple, romantic phrase “I love you.” Plucking into its tight linguistic weave and pooling a space for the (female) body, Irigaray inserts a necessary preposition: I love to you. The pre (before) position (place) incorporates a very different mode of address to the beloved other. Rather than subsumed into one, two produce a rhythm of in-betweenness that bleeds in harmony rather than a single note. At stake in this de-possessive coupling is a shift in the logic of binaries to one of intimacies, involving both closeness and autonomy. This alongside-ness in Gray: White/Blue/Orange (2013) incorporates the compositional tactics of the diptych, often present in Langford’s oeuvre.

For Gilles Deleuze, the diptych transitions the painting from one of vibration to one of resonance. Two bodies, side by side, hearts a-buh… a-buh… a-beating. How do we account for a spectrum of pre-positions? How can we, in relation, maintain the spacing of the à in our tête-à-tête, coeur-à-coeur, corps-à-corps (which includes the play of tops and bottoms)? Throughout Langford’s oeuvre the diptych expresses subtle and profound beauty resonant across routes of relation, having and holding difference.

Almost imperceptible are the everyday, quiet shifts in gait, scent, rhythm between you and I. Micromovements, a slight shift in posture. With nothing to hide, we have nothing to lose. To become imperceptible, write Deleuze and Felix Guattari, is “to have dismantled love in order to become capable of loving… To paint oneself gray on gray.”5Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, trans. Brian Massumi (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987), 197.

References