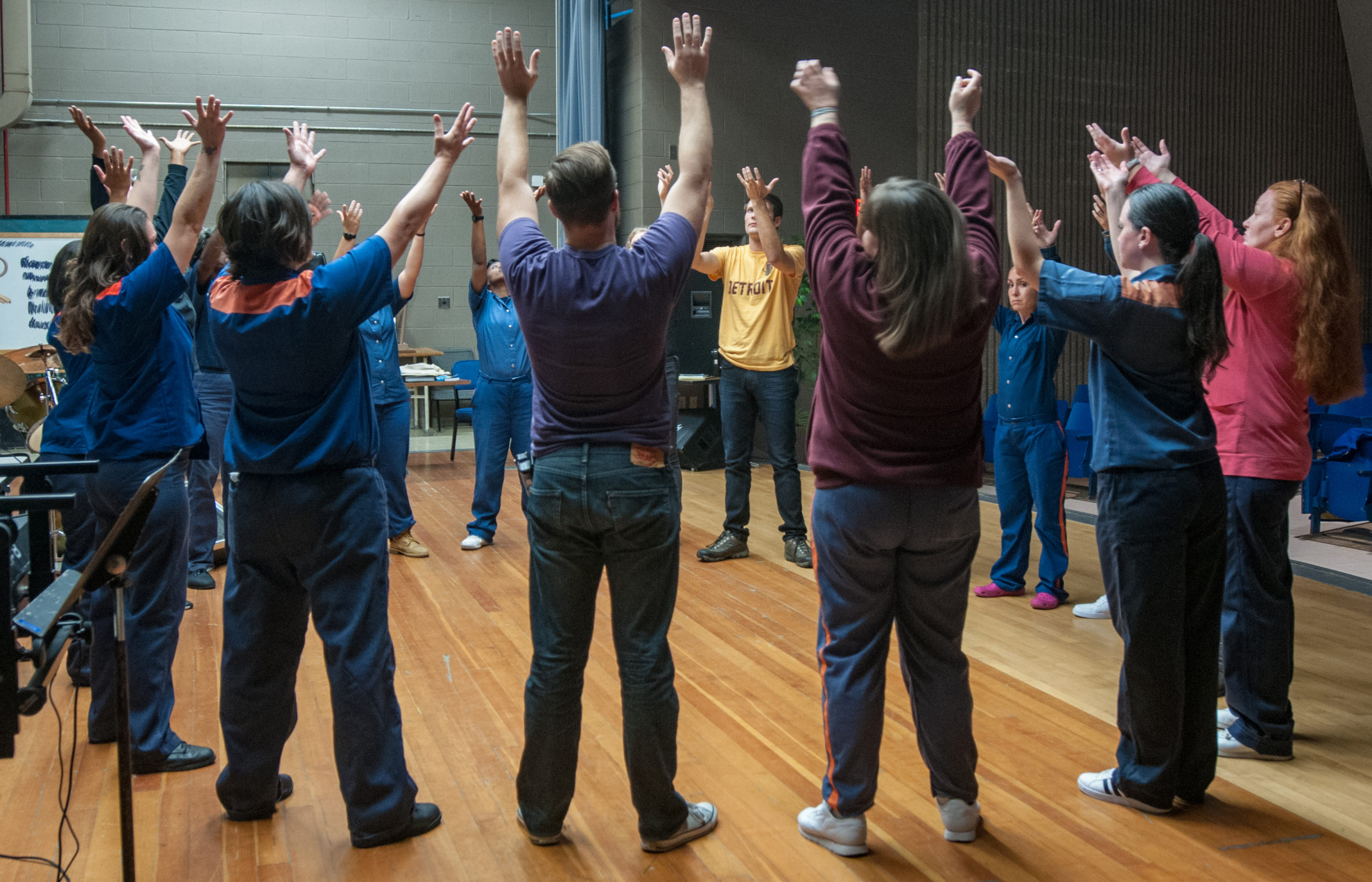

Jane (this is a pseudonym; prison policy does not allow the use of her real name) joined Shakespeare in Prison because she was bored and wanted to try something new. She was boisterous, loud, and good-humored. The energy she brought into the room was contagious, and it sparked something in me. I knew I was going to love working with her. We were less than a year into our work at Women’s Huron Valley Correctional Facility, and we were still figuring out exactly what we were doing. I had been trained and was working as an actor, director, and teaching artist, but I had grown increasingly frustrated by the limitations of traditional theatre as performed for passive audiences — people who simply show up, sit down, and watch. While I loved (and still love) this kind of theatre, it was not, on its own, enough for me. When I learned about Shakespeare Behind Bars, the oldest program of its kind in North America, I knew right away: I wanted to do that. I could take my skills and passion for theatre into a prison and see if I could make a difference. But I’d never done this kind of work before, and I needed to approach it in a way that was new to me - to let go of how things should be done and just let the process unfold itself. I founded Shakespeare in Prison determined that it would be developed by the entire ensemble - that I would be there to facilitate, guide, and encourage, not to direct or teach as usual.

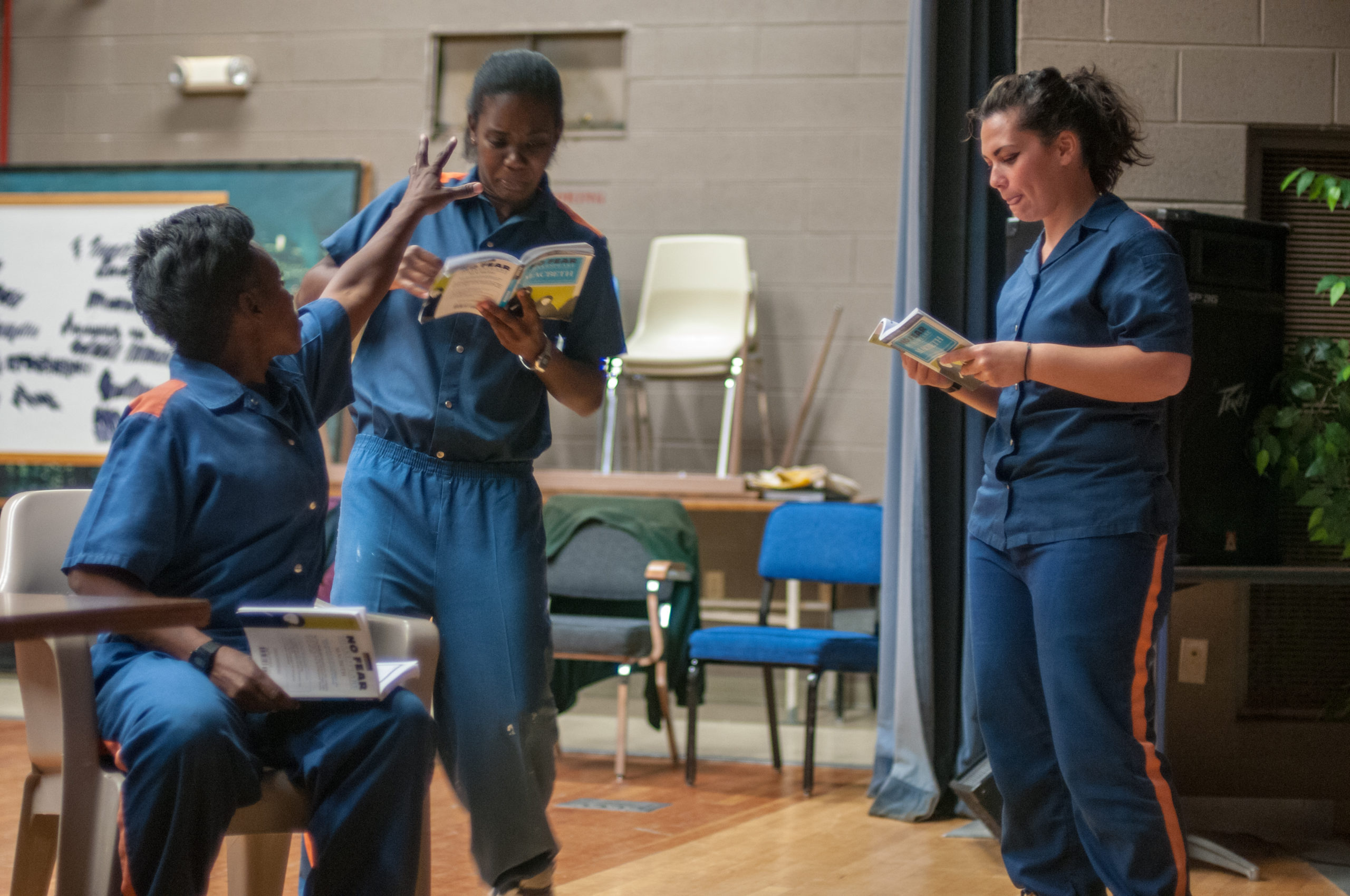

The day I met Jane, we were exploring the monologue from Richard III (act 1, scene ii) in which Lady Anne mourns her father-in-law’s death as his corpse is borne across the stage.

Set down, set down your honorable load,

If honor may be shrouded in a hearse,

Whilst I awhile obsequiously lament

Th’ untimely fall of virtuous Lancaster.

Poor key-cold figure of a holy king,

Pale ashes of the house of Lancaster,

Thou bloodless remnant of that royal blood,

Be it lawful that I invocate thy ghost

To hear the lamentations of poor Anne,

Wife to thy Edward, to thy slaughtered son,

Stabbed by the selfsame hand that made these wounds.

Lo, in these windows that let forth thy life

I pour the helpless balm of my poor eyes.

O, cursèd be the hand that made these holes;

Cursèd the heart that had the heart to do it;

Cursèd the blood that let this blood from hence.

More direful hap betide that hated wretch

That makes us wretched by the death of thee

Than I can wish to wolves, to spiders, toads

Or any creeping venomed thing that lives.

If ever he have child, abortive be it,

Prodigious, and untimely brought to light,

Whose ugly and unnatural aspect

May fright the hopeful mother at the view,

And that be heir to his unhappiness.

If ever he have wife, let her be made

More miserable by the death of him

Than I am made by my young lord and thee.

– Come now towards Chertsey with your holy load,

Taken from Paul’s to be interrèd there;

And still, as you are weary of this weight,

Rest you, whiles I lament King Henry’s corse.

Many ensemble members identified with Anne’s bitterness, grief, and desire for revenge, but this woman honed in on something very specific. She said that Anne wanted to take her internal pain and make it external, and she tried to make us understand what this meant, choosing words deliberately but ultimately becoming frustrated. As the conversation continued, she stayed focused on her script, looking up now and then but clearly deep in her own thoughts. I got the sense that her insight was not academic: it came from personal experience. I felt she was doing what I hoped we could all do: she had used Shakespeare as a tool to express herself, gain perspective on her life, and cultivate empathy for herself and others. I hoped that empowerment would follow.

A week later, we took turns performing the piece. When Jane volunteered, she said with pride that she had memorized part of it. She ran on stage, trying to get to the coffin, as two people tried to hold her back. She ricocheted between unrestrained grief, resignation, and rage. Another participant said that Jane had seemed overwhelmed by emotion and unable to detach. Jane said she had wanted people to try to console her - to get in her way and try to “bring her back to life.” She said had tried to build on what she saw in other ensemble members’ performances. She had also drawn on her own experience of losing someone when she was very young.

She said she was hooked; that she had had no idea there was anything like this out there. She was my age - in her late twenties - and had been incarcerated for many years after committing a violent crime when we were barely adults; when my toughest challenges were deciding which posters I needed in my dorm room and which shoes to wear to an audition. She alluded to a traumatic childhood and a fraught existence behind bars. Now she was determined to do better - to heal - and she believed that Shakespeare could help her do that.

She frequently challenged us. She had an undeniable, unshakable passion for the group and a commitment to honesty that, coupled with a past that had not equipped her to do otherwise, frequently expressed itself in a caustic way. Conflict came with her - she seldom instigated it, it just seemed to follow in her wake - as it had elsewhere in the prison and throughout her life. But where others in her life had abandoned her and any hope that she could do things differently, our ensemble took a collective deep breath each time a situation arose and worked through it with her.

You have a right to your feelings.

We care about what you’re telling us.

We know your heart is in the right place.

We want to help you find more constructive ways to communicate.

We believe you can learn to do better.

We are not kicking you out of this group.

We value you as a person, no matter your faults.

And she learned to do better. From my notes at the time:

[She] responded to a woman who had been directing some negative criticism toward her by thanking her for being honest, putting what she had said in her own words to show she understood while responding, giving details of what made her feel the way she did, and asking the other woman to meet her halfway… It was really exciting and inspiring to observe how calm, respectful, and constructive she was with no coaching at all. This is a skill that is going to benefit her for the rest of her life, and I’m so happy for her that she seems to have mastered it.

She left the group two and a half years in when she was not cast in the role she wanted. It was a very brief departure. From my notes:

The ensemble member who turned in her book last week appeared in the doorway of the auditorium and beckoned to me. “I’ve been feeling really, really bad,” she said. “I’ve been crying and sad ever since I quit.” She said that she’d called several of her friends and family on the outside to talk it out, and all of them suggested that she come back. A former ensemble member who was released earlier this year was particularly strong worded, reminding her of another member’s history of not getting the part she wanted three years in a row and staying with the group nonetheless. This ensemble member hadn’t realized that, and it made her think. “Really, what it is, is I’m a spoiled brat,” she said, smiling a little. She’s decided to stay with the group, believing that this new perspective of not getting exactly what she wanted will teach her something important and give her an opportunity to grow. “Shakespeare has been such an important part of my recovery,” she said. “I don’t think you even understand how much.”

She saw herself in Shakespeare’s characters over and over. Her connection to the material deepened. It began to work on her in ways that surprised her. She found herself writing - plays at first, and then screenplays, essays, poems, a memoir - delving into past experiences that had been unspeakable and using her writing to articulate them, share them, and connect with others. She was embarrassed at first to share her work, but, greeted with enthusiasm from her earliest readers, she plunged headlong into this new outlet. She produced and directed her own play at the prison. She wrote music for it. She even performed in it, replacing an actor who suddenly had to drop out.

Sometime later, she pulled me aside to read me an essay she had written about her life. From my notes:

It is a powerful piece, describing intense trauma that she experienced as a child and the following self-destructive choices she made that culminated in the crime for which she is incarcerated. She also wrote about her journey in prison toward healing. When she finished reading, she began to cry, talking about how hard it is to revisit these old wounds but how much writing about them helps. She emphatically stated that the reason she’s been able to do this has been her involvement in our group. Being able to explore so much through the characters, learn about storytelling, gain confidence and self-esteem, and learn to more constructively express herself and manage conflict has been a game changer for her. She is nearly ready to share her experiences widely and make some kind of impact, hopefully with young girls facing the same challenges she did.

This ensemble member has come a very long way from when I first met her. “I don’t think you can understand how much this has meant to me,” she said. “This group has changed me. You are my inspiration.”

“There could be no higher honor,” I replied. “This is what we hope the program can do for everyone. And I want you to know that you inspire me, too.”

She became so prolific that she regularly ran out of paper and wrote on envelopes, the backs of letters she’d received - any scrap she could find. She frequently came to our meetings exhausted because she had spent the whole night writing. Her dedication to the group was still remarkable, but she began to take on smaller roles. When called upon, she stepped into a large role but was honest with us that, because of her writing, she couldn’t commit to memorizing the lines. When the woman who’d vacated the role found that she could play it after all, Jane firmly insisted that she take it back. It was about the group. It was not about her.

People who’d known her for years said she’d “grown up.” She checked in with me frequently, and I did what I could to support her. “I think everyone has a ‘better person,’” she told me once. “You are my better person… I feel like you’re raising me. No one raised me at home. I’ve changed because of you.” It’s never been easy for me to accept praise, but this was different. I had to take it in - to believe that I could be this person for her - because I knew that if she was saying it, it was true. I’d known from the beginning that using theatre in this way had the potential to empower people and dramatically alter their lives, but I’d never considered the possibility that that could have as much to do with me as with the art form. And that is incredibly humbling.

Eventually, other commitments filled up what had once been a near-empty schedule, and we saw less and less of her. I quietly asked her one night whether or not she was still in the group. “I’m half in,” she replied. I reminded her of what she already knew - that halfway wasn’t going to work. She said she would think about it. She came to a few sessions after that, and then her time in the group was over.

… Or so I thought. A few months later, Jane appealed directly to our staff partner, insisting that she needed to come back to Shakespeare. “I can’t do this [prison] without this group,” she said. “It’s not that I want to come back. I need to come back. Shakespeare is a part of me.” The ensemble members all understand the truth in those statements, and we welcomed her upon her return.

“Leaving the group for that short amount of time was like having a baby,” she said. “It makes you a better person, but then you become incapable of properly taking care of it. And then you realize that raising your child is not an option because it makes you better.” She paused. “And that’s the truth.”

“I’m back. I’m not quitting,” she added. She knows she has more work to do and is eager to continue to grow.

The difference in this woman now from when I met her five years ago is astonishing. It’s breathtaking. She has skills, dreams, and ambitions. Shakespeare in Prison has had something to do with that. And I’ve had the honor - and the joy - of walking this path by her side. In a place where it is easy (and understandable) to succumb to a darkness I can’t fathom, she’s shown me greater strength, determination, passion, forgiveness, and humor than I knew was possible. Her work has empowered her. It’s empowered me, too.

If prison saved my life, Shakespeare in Prison helped me rediscover who I really am. After almost a decade of drug abuse, I not only found myself in prison for a five-year sentence, but realized that I had been entirely consumed in my addiction and no longer had much of an identity. That all began to change one September evening in 2013.

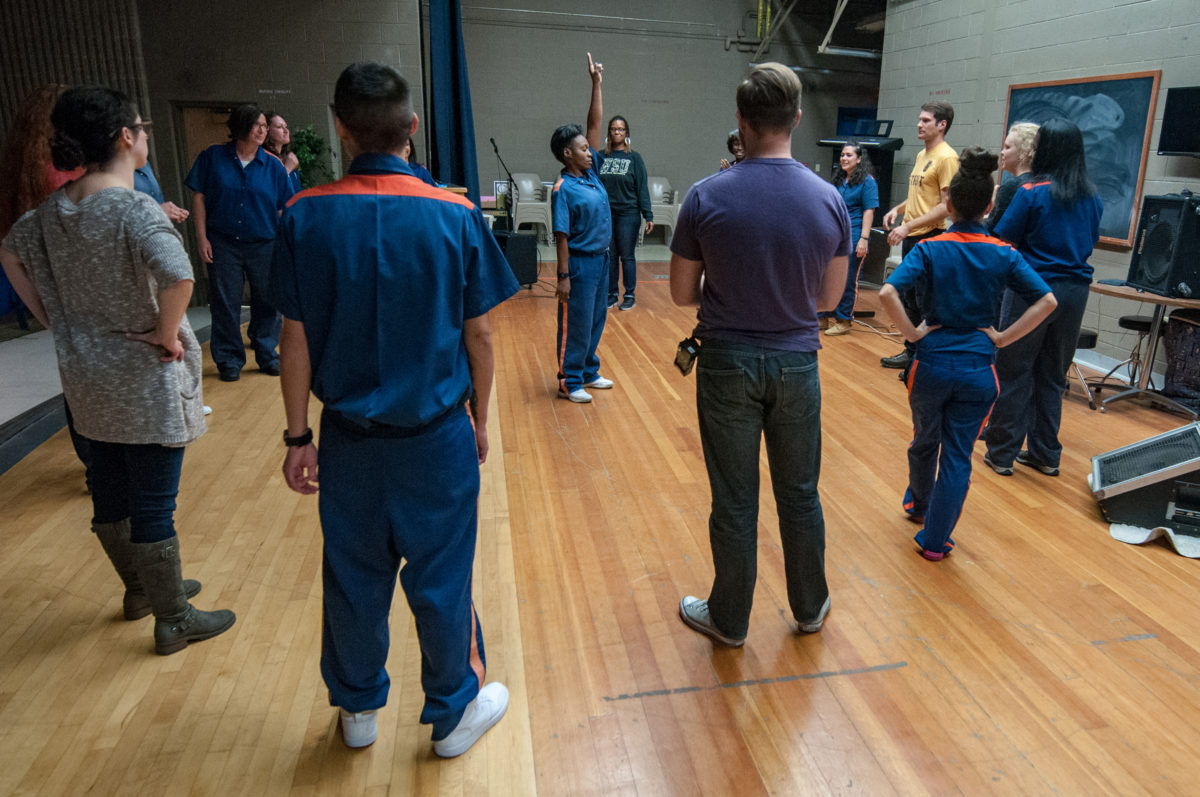

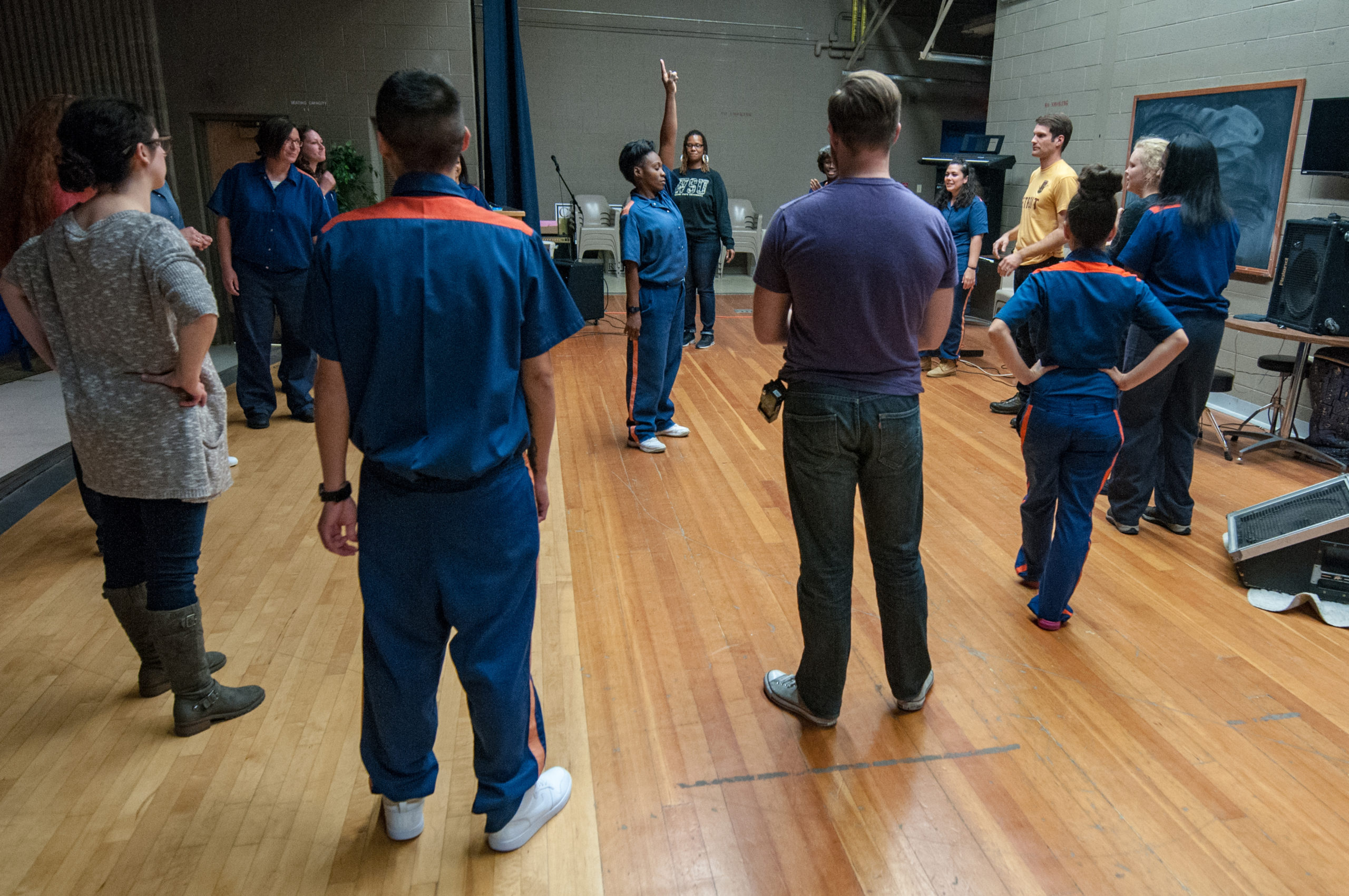

I had been an inmate of Women’s Huron Valley Correctional Facility for six months and had grown accustomed to being known by my last name, prison number, and crime. Imagine my surprise when I walked into the auditorium and three strangers greeted me with excitement and enthusiasm, offering a handshake and their first names. I felt like a human again! For the next two hours, I forgot I was in prison; I’ve felt that way every rehearsal since.

I’m not entirely sure if “rehearsal” is the appropriate word to describe the five hours we meet each week. Although our ultimate goal at the end of nine months is to perform a full production of a work of the Bard’s, there is much more involved than a performance. We acquire a myriad of soft skills such as effective communication, the ability to work with a diverse group of people, as well as critical and creative thinking skills.

The most important lesson I’ve learned through my participation in Shakespeare in Prison is that perfection is overrated. I have always been a bit of a control freak, constantly pushing every person and situation to be molded into my idea of how it “should be.” I know how that you can’t control what other people do; all you can do is control how you react to people and situations. Not everything is going to work out “perfectly” the way I would like, and I’m ok with that because it usually works out the way it should.

I will be leaving WHV and re-entering the “free world” in five days. I’m anxious but excited to go home and be a sober mom, daughter, sister, niece, and friend. I’m incredibly grateful to have had the privilege to be an ensemble member of Shakespeare in Prison. The four seasons I spent in the group have empowered me and given me the tools to be the best version of myself. Tomorrow I will enter that auditorium for the last time to say goodbye to the women (and two men) who have given and taught me so much. It will be bittersweet, to say the least, but I know I will carry them with me always.