Kylie

Lockwood

Simone DeSousa Gallery

November 9th – December 21st, 2019

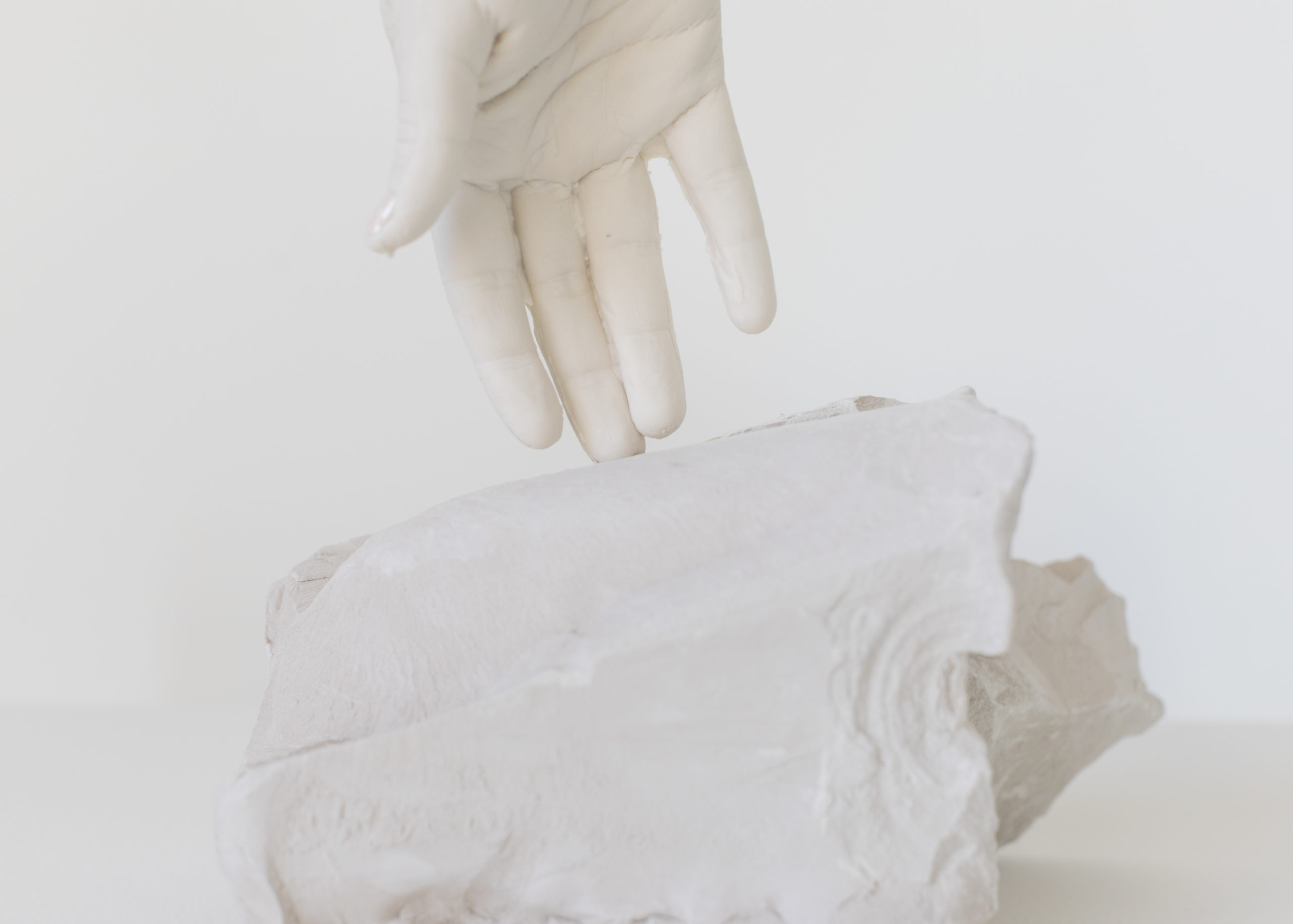

Fragmented hand pieced together in new order

Broken lower leg with its pieces being held inside the knee

Walking into the Simone DeSousa Gallery in the winter of 2019 took me back to the compound fracture I witnessed as a girl. Two neighbors, one on foot, one on a bike, collided resulting in a U-shaped forearm. The body - displaced and nonfunctioning - described a perfect bell curve through the shirt. The shrieking of the striker and the struck faded down the block. It was an explosion of trauma from an otherwise unremarkable, unmemorable sidewalk passing of girlfriends. Innocence and accident forged into incident. My first site of the body - broken.

This body of work by Detroit artist, Kylie Lockwood, opened up a gash in time, like ghosts falling from a mirror. A sort of rock face of shale, a mountain shivering into chips. It is the only visual expression I have known that felt like becoming a mother.

What happened to this presence, obvious in its feminine form but not especially anyone, but rather all of time wrapped up in the feminine. Lockwood used her own imprint as a shell portal to the impossibility of female perfection / inspection / depletion / exquisiteness. The experience of maternity / eternity. The perpetual treading of womanhood no matter your background or resource. Something in that room was heaving - I took a scrap from my pocket and scribbled this way and that. Like someone reading journal pages on a townsquare stump. I felt how could she dare brave this on behalf of so many? How did she trick history back from the dead with no promise of the satiny nippled perfection the marble she references lied about for centuries? The O zone coverage of that lie launched me at her-- tell - How did you find this? We don’t have to make up words for it anymore - here it is. In this rectangle room. What led you here?

Women have javelined at the complexity of their experience with every art supply. Niki de Saint Phalle, Frida Kaho, Kiki Smith, Patti Smith, Kara Duncan, Leonora Carrington, Alice Neel, Elizabeth Peyton, Faith Ringgold, Nicole Eisenman, Mickalene Thomas, Eva Hesse, Senga Nengudi, Phyllida Barlow, Ursula von Rydingsvard, Judy Chicago and on and on, you don’t have to like them or even know of them - but really, is just being alive while female that compelling? Evidently. This is historical work that Kylie Lockwood puts on display in becoming a sculpture.

Thighs in slight Contrapposto

Left hand and leg positioned at rest

Thighs in slight Contrapposto

Left hand and leg positioned at rest

Detroit hasn’t seen an expression through human form knock-out such as this since I moved here in 2004. Not sculptural anyway. Lockwood accepted an invitation from me to share fragmentary notes on this exploration of torsion and we readily agreed that each side would regard texts as prompts as a means of looking at the experience of the sculptural work. We met at the gallery and paced quietly. Women have a sadistic survival capability to allow even for the accommodation of a lava flow beneath everything. Running a company, spitting at microphones in punk bands, dancing on floors, serving up apple sauce and languishing in carpool cues. Lava. This exhibition makes a trifle of the post-centric days we curate - Lockwood went back home on this one. Time has passed since this show but a gnat’s life in comparison to the block and tackle pyramids of this body of work. There is so much work in this work. When I entered this space the lights were off, you will note the gray of the images recorded with my phone. Clouds inside. Lockwood hit a Doris Salcedo on the Richter scale and showed us work that had to be seen and encountered not scrolled. She is deeply embedded in a body of next phase work that digs deeper into icon and the materialized gorgeous fracture. I think by the time it is mounted I will have recovered well enough.

Thighs in slight Contrapposto

Left hand and leg positioned at rest

Thighs in slight Contrapposto

Left hand and leg positioned at rest

Thighs in slight Contrapposto

Left hand and leg positioned at rest

Thighs in slight Contrapposto

Left hand and leg positioned at rest

Thighs in slight Contrapposto

Left hand and leg positioned at rest

Thighs in slight Contrapposto

Left hand and leg positioned at rest

Dear Addie,

The categories you outlined are such an astute mapping of the work! Here are my notes, they are definitely incomplete. All the categories you outlined are relevant. The ones at the end that I did not get to are no less relevant. Writing is a slow process for me. Please reach out if you have any questions or if there is anything you want more light on.

With gratitude,

Kylie

The most distinctive feature,

the gesture of Aphrodite’s right hand

Subjectivity

Crucial

This work is all prompted by a shift in subjectivity

This work is a performance of coming to terms with a shift in subjectivity

This is the first act. The first attempt…

Michael Stone-Richards messaged me on this topic after the gallery talk:

Really enjoyed listening to you at Simone’s, Kylie, and could have listened much longer! There are some compelling and complicated /complicating questions raised by this BODY of work and I find esp fascinating yr performance of coming to terms with this. This is one of the aspects most important to me and the mark of truth / encounter: that you are coming to terms with a turn in subjectivity, a transformation requiring time.

I mentioned the genre of poetry in which the work speaks to us, works on us. Rilk’s Archaic Torso of Apollo is the essence of this in modern form. In the Romantic form, where this genre is common, there is of course Keats’ Ode on a Grecian Urn! It is when the work suddenly speaks, addresses us that is key. I felt, but on this I am not sure, that Sophie Eisner was struggling with this aspect of yr thought and so it wd have been interesting to elucidate this since such an idea of the work being capable of an existential effect is almost alien...and yet...

The poem Michael Stone-Richards sent:

Archaic Torso of Apollo

Rainer Maria Rilke

We cannot know his legendary head

with eyes like ripening fruit. And yet his torso

is still suffused with brilliance from inside,

like a lamp, in which his gaze, now turned to low,

gleams in all its power. Otherwise

the curved breast could not dazzle you so, nor could

a smile run through the placid hips and thighs

to that dark center where procreation flared.

Otherwise this stone would seem defaced

beneath the translucent cascade of the shoulders

and would not glisten like a wild beast’s fur:

would not, from all the borders of itself,

burst like a star: for here there is no place

that does not see you. You must change your life.

Deterioration shows up in many ways in this exhibition:

Deterioration of my body’s ability to hold a pose,

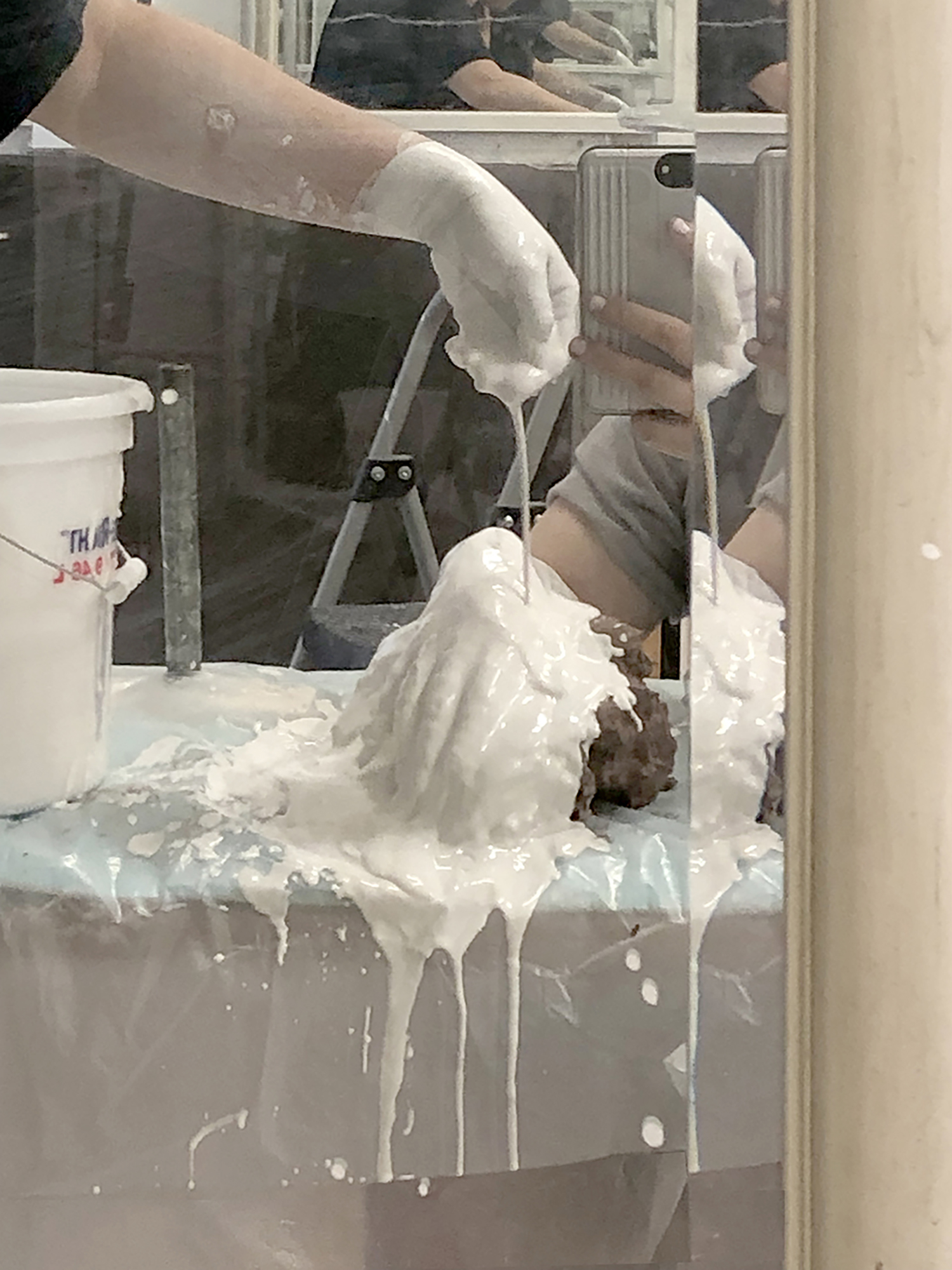

Deterioration of the plaster mold attempting to capture stillness from my animate surface.

Deterioration of the fossil, the porcelain cast in the process of harvesting it from the mold. The ceramic membrane straining to pull out of the rigid container in which it was formed.

Deterioration of the porcelain body as it moves, shifts, and shrinks, vitrifying under the heat of over 2200 degrees on beds of silica sand in the kiln.

Deterioration of the reconstructed final pose exhibited in the gallery. The sculpture Attempting Accroupie appears still but is in fact moving. The very ground beneath the sculpture is shrinking, as the block of wet clay it stands upon slowly dries. The stress of an uncertain ground shows up over the span of weeks in gaps and perceivable shifts of the sculpture’s form. A fracture at the joint of the left knee expands. The plates of the back veer away from each other. The left foot once firmly planted shifts askew. The toes of the right foot mar the condensing ground as it moves beneath them.

Then there is the deterioration of the sculpture I am empathizing with, the Crouching Venus whose pose I am re-performing. This specific sculpture is a Roman marble copy of a Hellenistic original that predates it by approximately 500 years. No remains of that supposed original form have been identified; it has undergone a complete deterioration. And the marble copy has been in the process of wearing away for the last 1800 years. Knocked down in the ancient city of Vienne, this marble Venus found its crouching body in a new orientation as it settled on the bottom of a river. An ideal representation of a female bather is submerged in water; the gravity it once defied grinding it into the bank of the Rhône. The movement of the river and its sediment slowly wears away the paint that once adorned the sculpture’s surface. Over a thousand years this sculpture exists unseen, as stone at the bottom of a river.

Perhaps having her body left in the river came as a relief. After holding a pose for as long as one can remember, what would it feel like to finally lie down? To stop holding? To merge with the ground? To deteriorate is a reality.

Permanence is an ideal.

The fate of sculpture is ultimately to break. To break is the point. To empathize with the ancient is to identify with the fragment; to feel the pressure of entropy through an abbreviated form in which time has chipped away.

It is important that all the different vernaculars of edges are apparent and coexist in these sculptures:

- The dripping liquid brim at the mouth of the cast; the material quotation of porcelain slip.

- The edge of actual breaks and fractures in the porcelain forms.

- Modeled marble to reference and echo the fragmentation and materiality of the sculpture I am communing with.

- The mold line, the point where my malleable flesh intersects with a rigid mold. Evidence of pressure. Evidence of misalignment.

- The surface of the mold as it intersects with my body. This is of course another edge but it produces more than one type of indexical mark. There is the cast and imprint of my body, the making of a fossil; then there is another encounter produced on this edge, the deterioration of the mold on my body. This type of edge is most evident in the chest of the central sculpture. You see all of these cracks and alterations to the surface that feel akin to the reference of a stone surface beginning to fragmentize. But these markings are from the plaster mold notwithstanding its interaction with my body. They are from my body breaking and fracturing the mold as it is made; deterioration of the plaster mold attempting to capture stillness from my animate surface.

When casting the chest, I had produced all of these support structures for my body so that I could hold the pose for the 45-60 minutes it took to pull a mold. All this preparation, yet the one thing I did not account for was the weight of my head. The psychology of this feels indisputable. As I held the pose the weight of my head and my decreasing ability to keep it perfectly aloft slowly pulled me out of the mold, flexing my body and breaking the surface of the plaster. This breakage and fraught physical interaction are recorded in the breast, chest, and neck of the central sculpture Attempting Accroupie.

It is important that all the different vernaculars of edges are apparent and coexist in these sculptures:

- The dripping liquid brim at the mouth of the cast; the material quotation of porcelain slip.

- The edge of actual breaks and fractures in the porcelain forms.

- Modeled marble to reference and echo the fragmentation and materiality of the sculpture I am communing with.

- The mold line, the point where my malleable flesh intersects with a rigid mold. Evidence of pressure. Evidence of misalignment.

- The surface of the mold as it intersects with my body. This is of course another edge but it produces more than one type of indexical mark. There is the cast and imprint of my body, the making of a fossil; then there is another encounter produced on this edge, the deterioration of the mold on my body. This type of edge is most evident in the chest of the central sculpture. You see all of these cracks and alterations to the surface that feel akin to the reference of a stone surface beginning to fragmentize. But these markings are from the plaster mold notwithstanding its interaction with my body. They are from my body breaking and fracturing the mold as it is made; deterioration of the plaster mold attempting to capture stillness from my animate surface.

When casting the chest, I had produced all of these support structures for my body so that I could hold the pose for the 45-60 minutes it took to pull a mold. All this preparation, yet the one thing I did not account for was the weight of my head. The psychology of this feels indisputable. As I held the pose the weight of my head and my decreasing ability to keep it perfectly aloft slowly pulled me out of the mold, flexing my body and breaking the surface of the plaster. This breakage and fraught physical interaction are recorded in the breast, chest, and neck of the central sculpture Attempting Accroupie.

From my press release:

The central work in this show Attempting Accroupie is a re-performance of the Crouching Venus, a Hellenistic model of Aphrodite at her bath. Originally created over 1800 years ago, Lockwood seeks to occupy the space of its form, to hold its pose, embody its posture and enact its stance. The artist sits low with her legs drawn up tightly beneath her. Stooping close to the ground, her arms reach across her body as her neck cranes to look over her right shoulder. Lockwood’s fallible body is attempting to fit an “idealized” form.

The pose of the Crouching Venus is a confrontation with gravity.

Stooping low to the ground low, the endurance to maintain this posture is great. It is difficult to get into, let alone hold for more than a moment without some sort of supplemental support. The body is sent in all of these angular negations of balance and counterbalance. The weight of one’s head becomes hyper apparent.

When I began making this work I could not even achieve the pose. In all of the Greek and Roman sculptures, the right leg is the load-bearing leg. The pose does not deviate from this structure. In attempting the pose, I encountered asymmetry in my body. My left leg was stronger than my right. This perplexed me at first. Then the reason became apparent: two-and-a-half years of carrying a growing being on mostly my right side thus shifting my balance to my left side had formed my left leg as the weight bearer.

I was reading Christine Mitchell Havelock’s book The Aphrodite of Knidos and Her Successors (2007) during the research for this show.

One of the purposes of her book is to show how the meaning of this original sculpture was distorted through art history and thus every subsequent sculpture of the goddess was wrongly perceived. Here are a few moments from Havelock:

“The Aphrodite of Knidos, the leading Greek example, required the most detailed reexamination, and while I was carrying this out, it became apparent that I had to confront the male-biased scholarship of both the past and present.”

“[At] the heart of the problem is the scholarly propensity first noted in my remarks about the Knidia, namely, the tendency to forget that one is dealing with a work of art and not its subject. A certain patriarchal bias is built into the long history of scholarly endeavor on behalf of Aphrodite statues.”

This work began in 2016 as an Iconoclastic investigation of Michelangelo’s sculpture of David and thus the lineage of Greek and Roman sculpture. For this show I wanted to revisit that work I had left unfinished. However, after experiencing a shift in subjectivity since the project began, I felt differently about my research, specifically the sculpture of Aphrodite. I looked at the image of the Crouching Venus and I empathized with it.

My empathy for this form shifted my thinking on the impetus of this work. I found myself feeling conflicted….

I am still seeking to interrupt the image of the ideal; however, rather than purely rejecting it, I am attempting to interrogate it from the inside.

I found Bruno Latour’s framing of his concept of Iconoclash helpful in describing this…

(The following is from my notes on his essay “What is Iconoclash?” from 2001.)

Iconoclash: when one does not know one hesitates and is troubled by an action for which there is no way to know without further inquiry whether it is constructive or destructive.

Suspending the urge to destroy

Looking at something one loved to hate but with a renewed sympathy. A craving for a carefully crafted mediation and asking what does one want to protect and what does one want to destroy

This topic is hard to give words to…

It is crucial. I could account and list the types of voids like edges, but the most important one to describe is the one I do not have language for yet. That void is contained in the thesis of this work. This work is the act of building language for that void.

From the press release.

Through the process of directly pulling plaster molds off her skin, Lockwood is making a fossil. The molds capture the performance of that moment; the trace of a living thing engaging in restriction and endurance. Lockwood substitutes porcelain, the material language of doll making she inherited from her maternal grandmother, for the canonical marble. Fragile porcelain skins are pulled from the molds while still soft. The stress of this transition shows up in cracks, abrasions and occasionally the collapse of the surface. These forms shrink when fired and become a concentrated vitreous version of her flesh. The work is hollow and perforated. Fractures and voids disrupt the conventional distinction between interior and exterior.

In this work I am both inside and outside myself. In attempting to hold a pose that requires a physical support system and exploring a subject position where my dependence on others has intensified, it’s fitting that this dynamic is echoed in my process. The help of my assistant Lisa Tolstyka has been crucial for me to occupy the plural state of within and without.

I have so much more to say here but I have run out of time. I think the main point is that the process and all its elements are vital aspects of my interrogation of this form.

This transformation requires time

Another thing we discussed in the gallery was that each step in this performance is time based. The last part being the movement of the sculptures on their drying clay bases