Externalize,

Extract,

Co-opt,

Repeat

There are two main ways a community can be exploited by private industry: externalized costs and wealth extraction. An externalized cost means that the costs of producing any given commodity are not accounted for in the costs of the product, nor are they taken as a loss by the company that produces the good. These costs, then, are not reflected on the balance sheets of producers. They are simply externalized to other people and communities.

For example, the global price of Iowa-grown soybeans and corn cannot account for the costs to treat nitrate runoff downstream, so the Des Moines Water Department must foot the bill instead, likewise, the market price of fish does not account for the costs to the fishing economy of New Orleans when inadequately processed nitrate pollution travels via the Mississippi into the Gulf of Mexico, causing a hypoxic die-off where all aquatic life within a 400-mile area are exterminated.

In Kentucky, for example, coal mining has sucked the groundwater from its basin in the process drying out - exhausting - wells that required massive public investment in water infrastructure – a burden that local governments cannot shoulder, given inadequate coal tax revenues. These unaccounted costs have led to water contamination across Appalachia. Another example:

Across Detroit, we shoulder externalized costs, too - whether through the health costs of air pollution caused by incinerating the suburbs’ trash, refining oil in 48207, or decreasing property values when the company US Ecology expands its operations on the east side in order to store radioactive waste.

Often, the private entities involved in externalizing costs have a single mission: to maximize shareholder value, rather than cultivate sustainable businesses. Thus, there is a real incentive to externalize the costs of a higher profit margin on the communities these industries call home.

Wealth extraction, on the other hand, is when an entity, often (though not always) those that deal directly in financial transactions, detects a vulnerable population, and profits from that vulnerability. Wealth extraction goes way past simply earning a profit by meeting a person’s needs or desires by providing a product. Instead, the extractive entity makes money (often increasingly) because the community cannot access the good or service. Usually this lack of access is created by an external circumstance. Car insurance redlining, subprime loans, land contracts, and rental furniture are examples of wealth extraction based on black Detroiters' historic lack of access to fair credit. Entire cities have been the victim of this type of extraction. A common manifestation is through the privatization of municipal water departments, unfair tax abatement deals, or, as a result of austerity, an over-reliance on private contractors to handle operations traditionally undertaken by trained city staff. Privatization is a process that has been proven, across the US, to increase costs and decrease quality of drinking water.

In 2012, Detroit’s Water and Sewerage Department paid $500 million in interest rate swap termination fees after they desperately tried to borrow beyond their debt limits following massive state revenue cuts. The result: Detroit residents paid higher and higher water bills. Thousands of Detroiters simply couldn’t pay - their water was promptly disconnected by a team of private contractors. Others paid, resented their neighbors, until they, too, couldn’t pay, and their water was also disconnected. These shutoffs compounded the exodus of long-term African American Detroiters from Detroit already underway after the mortgage foreclosure crisis of the 2000s.

Another example of wealth extraction in the city of Detroit is funneling tax dollars, through Tax Increment Financing, into certain neighborhoods to build stadiums and condominium high rises. Tax Increment Financing, or TIF, is generated by a formula where taxes captured via increasing property values stay within the neighborhood where property values are rising. This prevents the circulation of public resource from one area of the city to another, or into parks, schools, or recreation centers. Detroiters understand that the city’s comeback is not for long-term Detroiters. TIF financing is one reason why.

We would argue that wealth extraction is the primary mode of exploitation that has created the regional inequalities cemented into Southeast Michigan’s social, political, transit, health, lending and media institutions. However, once cycles of wealth extraction are established, externalizing costs on that community becomes all the more easy. Vulnerability breeds desperation for jobs, which often means that communities will accept externalized costs like pollution in the name of jobs. Both wealth extraction and externalizing costs thrive in the dark.

But how and why would communities allow these destructive processes to continue? One important tactic that is utilized by corporations to create complicity with their extraction / externalization model is their seemingly unfettered power to co-opt and appropriate. When communities demand corporate accountability, their words are often used against them. Corporations mirror the language, but then act in a way that is opposite of the intended meaning - always proving their loyalty to shareholders above all else.

Emergency Water Relief Station, Flint, MI, February 2016

“No New Jails” Prisoner Rights Protest, Detroit, MI, 2016

MSU “Stop Richard Spencer” Protest, Lansing, MI, 2018

MSU “Stop Richard Spencer” Protest, Lansing, MI, 2018

Logging memorial along Enbridge Line 5 Pipeline, Upper Peninsula, MI, 2014

For example, in 2016 the Equitable Detroit Coalition, a group of neighborhood organizations and concerned citizens, waged a grassroots campaign and created Proposal A, a ballot initiative for a Community Benefits Ordinance in Detroit. The ordinance would require a community process ending with a legally binding agreement from developers using public funds. Almost overnight, over one million dollars were deployed into promoting the corporate-backed Proposal B, using the same language and logic of Proposal A. In fact, Proposal B itself was a carbon copy of the people’s initiative - with one slight difference: an omission. It was missing the clause about legal enforceability. It won by a very slim margin.

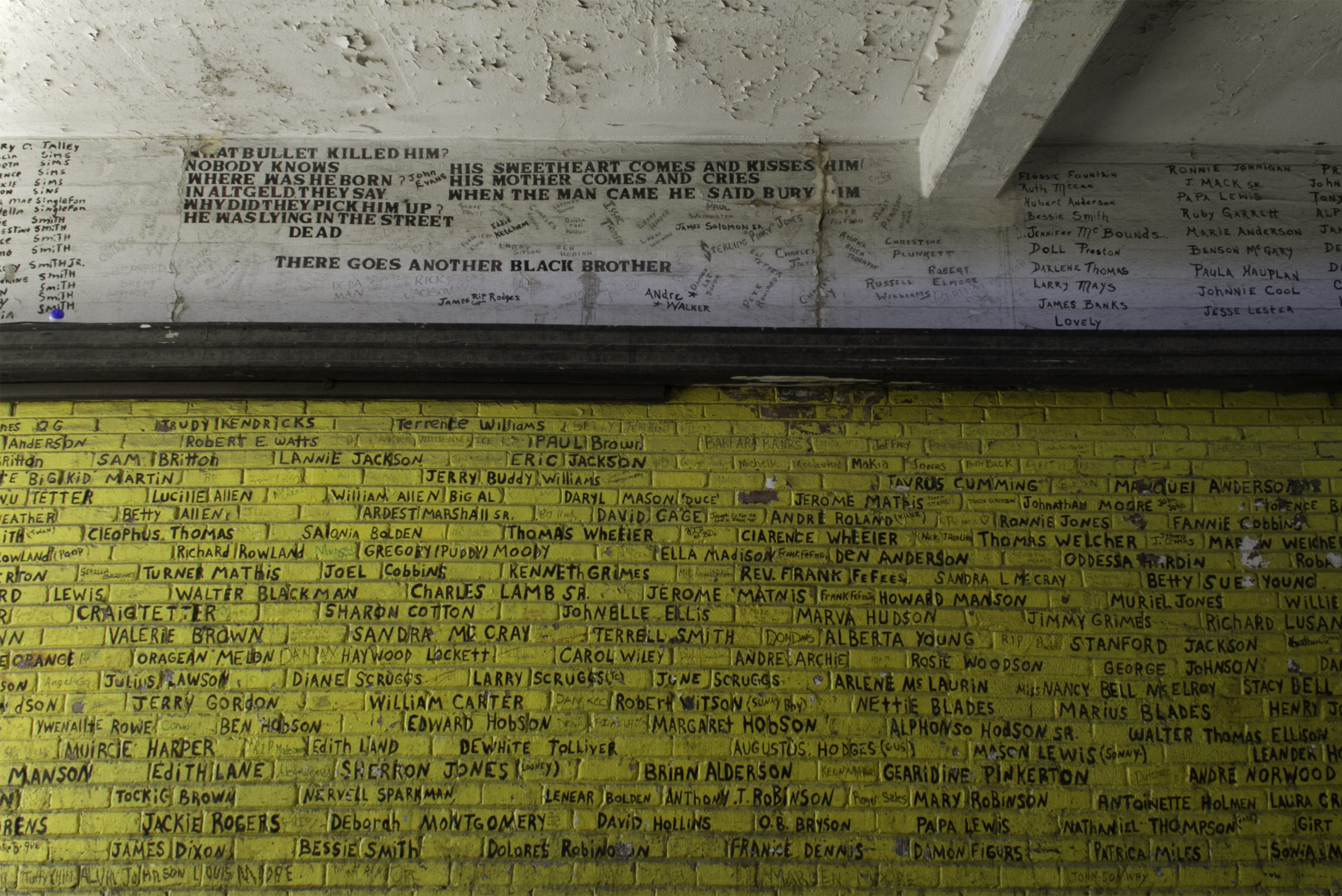

Fact-based political discourse requires a transparency that puts the fear of god into companies that operate by extracting wealth from vulnerable populations and hiding the true costs of production. A discourse that holds private industry accountable depends on having an egalitarian space - a commons - for residents to come together to share experiences and information, activities that lie at the heart of democratic expression. Historically, parks and schools have served this purpose, and Detroit is no exception. From the union rally of 1937 where thousands flooded Cadillac Square in support of city-wide sit-down strikes, to the Newspaper Strikes of the mid 90’s, publicly owned parks and streets open up space for collective solidarity and opposition.

It is this destruction of the commons, whether through wealth extraction, externalizing costs to a community, or privatizing public space, that claiming public space through protest interrupts.

Across the country, public-private partnerships are becoming the norm for parks, hospitals, and schools. In Detroit, Rock Ventures, a holding company responsible for 1/4 of the home mortgage foreclosure crisis in Detroit - one of the hardest hit in the country - now owns most downtown buildings. Rock Ventures operates a security command center operating from the basement of Detroit's Chase Tower, functioning as a panopticon capturing a constant livestream through hundreds of unblinking video cameras and security forces throughout the public parks and streets. Over the past few years, various news outlets report that Quicken Loans employees work with private security as part of a two-pronged effort to monitor and control activity on public space. With regard to private security practices, attorneys from the American Civil Liberties Union warn that since they are not subject to records requests under the Freedom of Information Act, there is far less transparency around private “policing,” which has deeply anti-democratic implications for anyone who is not a corporation.

In 2014 specific organizers from the group Moratorium Now! were identified and had their social media accounts monitored by Quicken Loans employees. The following year the ACLU of Michigan won an interim decision in favor of the activists’ right to peacefully assemble without interference – but, it is uncertain for just how long those rights will hold in a city that is constantly under siege through an agenda of extracting, externalizing.

Standing Rock, ND. 2016

“Man Camp” Construction, Bakken Shale, ND, 2012