I’ve written a short text for our panel discussion today1Reese Williams presented these reflections as part of the symposium Re-Seeing DICTEE, at BAMPFA, University of California, Berkeley, in April 2018. … - some reflections about my experience of reading DICTEE during this past winter, but before I begin let me offer two brief notes.

I’d like to thank Theresa’s family, the director, and curators here at the University Art Museum, and probably a few people behind the scenes, for creating The Theresa Hak Kyung Cha Archive here at the Museum, and for continuing to stage exhibitions and events about her work. I think this reflects a deep understanding of the potential of what a university can be.

Second, just to put things in context, I was a friend and classmate of Theresa’s in the MFA Art program here at UC Berkeley back in the 1970s. Our friendship continued after graduate school, and we both ended up moving to New York City. In 1979, I founded Tanam Press and Theresa was the most active contributor to that project in its early years, offering two pieces to the first Tanam book, HOTEL;2Hotel (New York: Tanam Press, 1980). editing the anthology of writings on cinema, APPARATUS;3Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, ed. Apparatus - Cinematographic Apparatus: Selected Writings (New York: Tanam Press, 1980). and then creating her book, DICTEE.4Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, DICTEE (New York: Tanam Press, 1982). When I started Tanam, one of my first actions was to encourage Theresa to work on a larger scale and create a full book.

The color she had decided upon was a dark maroon and we searched for the correct Pantone number to specify for the printer. My mind wanders for a bit immersed in this color… In those days, in lower Manhattan, it was possible to go out for an afternoon errand and see an undulating wave of this “dark maroon color” moving down the sidewalks of First Avenue or some other street. Groups of Tibetan monks had been sent to New York and were living in temporary spaces in the city. One million people had been killed on the Tibetan Plateau, 6000 monasteries were burned to the ground, and more than 100,000 people crossed over high mountain passes in the snow of winter, to escape into India. From their refuge in Dharamsala, the Dalai Lama and other Tibetan leaders, in a gambit to resettle their culture, were sending groups of monks, in their dark maroon robes, to Europe and to the United States.

About two hours into my reading, the word “bandwidth” shows up in my thought flow. In the realm of computers and communication networks, the word “bandwidth,” in a simple definition, refers to the amount of data or information that can be carried from one point to another, in a given period of time. A network or device that can receive and transmit a large amount of data, at high speeds, is said to have “high bandwidth.”

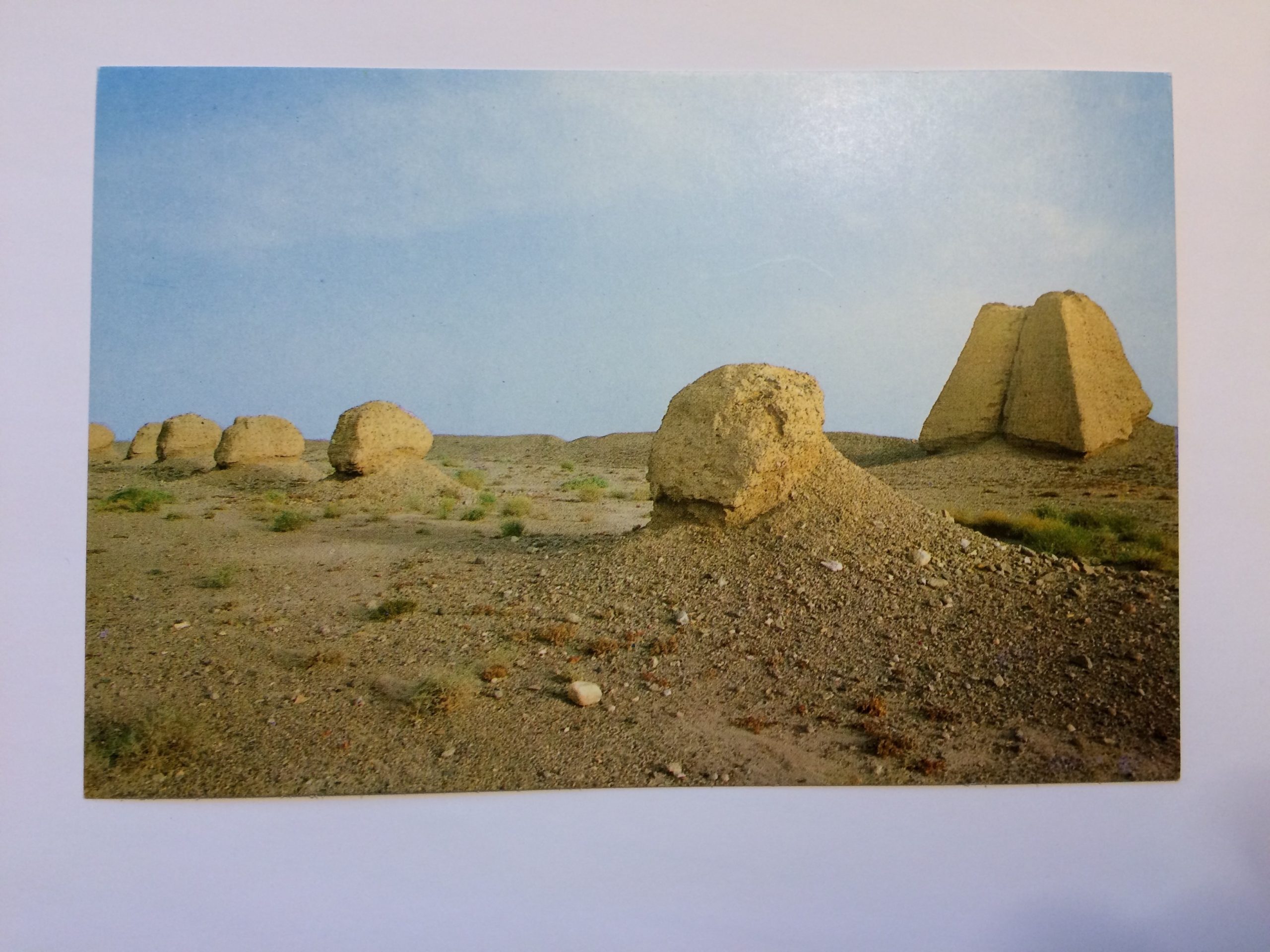

I believe there is value in bringing the word “bandwidth,” as a metaphor, into a discussion of DICTEE. If one considers all of the realms and references in the book, one could say that DICTEE is a very “high bandwidth” artwork. The book touches mythology, Taoism, healing, the Catholic religion, the Greek classics, the history of Korea, her family history, the primal impulse of speech and the acquisition of language. And it makes reference to Sappho, St. Therese of Lisieux, Yu Guan Soon, Jeanne d’Arc, Persephone and Demeter, ancient ruins, calligraphy, films and acupuncture and anatomy diagrams. I’m not an art historian, but I can’t remember another “artist book” or work of contemporary art that operates at such a high bandwidth.

I think Theresa learned a recognition of this state of mind more from literature than from contemporary visual art. Perhaps she received a subtle permission to explore “high bandwidth” from some of the great writers she admired and loved to read. In this moment, I’m thinking of Marguerite Yourcenar, especially the vast scale and literary ambition of Memoirs of Hadrian. And Roland Barthes as well. If one takes all of his books together, as one dynamic, it is as if he is saying, “We can take a good, close look at everything.”

However, to be clear, I’m not suggesting that Theresa adopted “high bandwidth” as an aesthetic strategy. I think it was the true state of her mind, just as it may be, in different ways, for many people who are dislocated and exiled from their home country and culture.

Imagine for just a moment that your home country has been invaded and bombed apart, that you are taken, at age 13, far away into a strange, huge country; that you land in a Catholic school where your prescribed activity is to study the Catholic religion, to learn the English language, to learn the French language and to study the Greek classics, as well as the usual math, science, U.S. history etc. And, outside the school building, it’s the 1960s in America - the cultural revolution, the civil rights movement, another unnecessary and tragic U.S. war in Asia, a wave of assassinations, and on and on.

My sense, just from small things I remember from our friendship, was that Theresa’s ability to take in and integrate all of the phenomena of her new life, and then, years later, to create a work like DICTEE, was only possible because of her grounding in her family - her mother and father, her siblings, and the Korean people. One could say that the main theme of DICTEE is the journey of “piecing together” a way home.

Flowing underneath the bandwidth of DICTEE is a deep underground river. This river opens to the surface at a well in the desert landscape in the last section of the book, “Polymnia Sacred Poetry.” On one level, this book is a complex work of contemporary art and literature, but on another level, the book is simply one woman telling her story, telling other women “what has happened.”

This type of story, this telling of “what happened,” has been going on, in one form or another, for thousands of years - in every village, in every town, and now in every metropolis. This underground river permeates DICTEE, greatly multiplying, on subtle energetic levels, the range and the speed of its bandwidth.

In this last section of the book, Theresa lets go of her experimentation with language.

The texture of the sentences becomes smooth and simple. In the scene at the well, where the older woman healer is giving the young girl the ten white packets to take home to her mother, I feel like I am watching a 16mm movie rather than reading a book. It is granular, luminous and electric.

Then, the young girl turns and makes her way home to her mother. And, in the flicker of a candle, this story comes to an end.

The next page of the book is blank, on both front and back. This page lasts for just the two seconds that it takes for your hand to physically turn the page, but for me it feels like a vast space - like when a teacher suggests, “Just let go of everything.”

Theresa then takes the reader into a “postface” type of territory, but it’s not a traditional literary postface, it’s more like a cadenza in a brilliant piece of music where the lead musician offers a virtuoso reprise of the last theme of the composition. She begins the cadenza pointing outward into the universe, with a Taoist text that lists ten stages to comprehend the “Way.” The ten white packets have metamorphosed into these ten stages. The page guides the reader in stepping down through the stages, arriving to the last one, the one which the healer had reserved for the young girl:

Tenth, a circle within a circle, a series of concentric circles

Then, she turns toward “home” once again, and two pages later, the young girl is back with her mother.

This time she is younger. And she asks her Mom to lift her up to the window so that she can look out and see all that is happening.

It’s past 4pm by now, the earth has turned ever so slightly and the sun is now in the west, so I move to a chair at the other end of my apartment. This window opens to the south, and I look out to see “what is happening.” Above the tree line, a large cloud is slowly moving to the right across the window frame. It is an unusually large cloud. During the past year, I’ve been seeing clouds like I have never seen before - huge, beautiful, ominous formations.

The water of our planet is on the move. And. . . our people will be on the move as well.

In a month or so, it will be monsoon season in Bangladesh. In the most recent global dislocation and exile, the Rohingya people have been raped and murdered out of Myanmar and forced into a refugee tent camp in a low-lying area of Bangladesh. When the rains arrive, these people, more than a million, will need to move again.

The United Nations reports that, as of January 2018, 65 million people are currently “displaced” from their homes. This number could double, triple, or even quadruple in the next 50 years as the climate of our planet changes. The Tigris is drying up, the Euphrates is drying up and the Ganges is starting to show stress as glaciers in the Himalayas recede. More water is moving up into the sky. And then down again, in stronger rains, larger floods, higher tides.

The light of this day is now fading to the dark, blue gray of dusk. My reading has been finished for a while now, and I am just resting and watching the flow of my mind. I notice that it roams into the idea, the possibility, that the reading of DICTEE, in a larger, historical perspective, may still be in its early stages. Yes, many people have read this book, and mant people have written about it. But these numbers could grow, in an expanding series of concentric circles, in the next 50 years. The dislocation and resettling of people, all around the planet due to climate change, along with the resulting political and economic pressures, will stretch and test our humanity in ways we are not ready to begin to envision. For many people, the people on the move, the question of “How to piece together a journey home” will be a constant churning pattern in their minds. The wisdom and courage of books like DICTEE may offer some of the inspiration and sustenance that people will need.

References