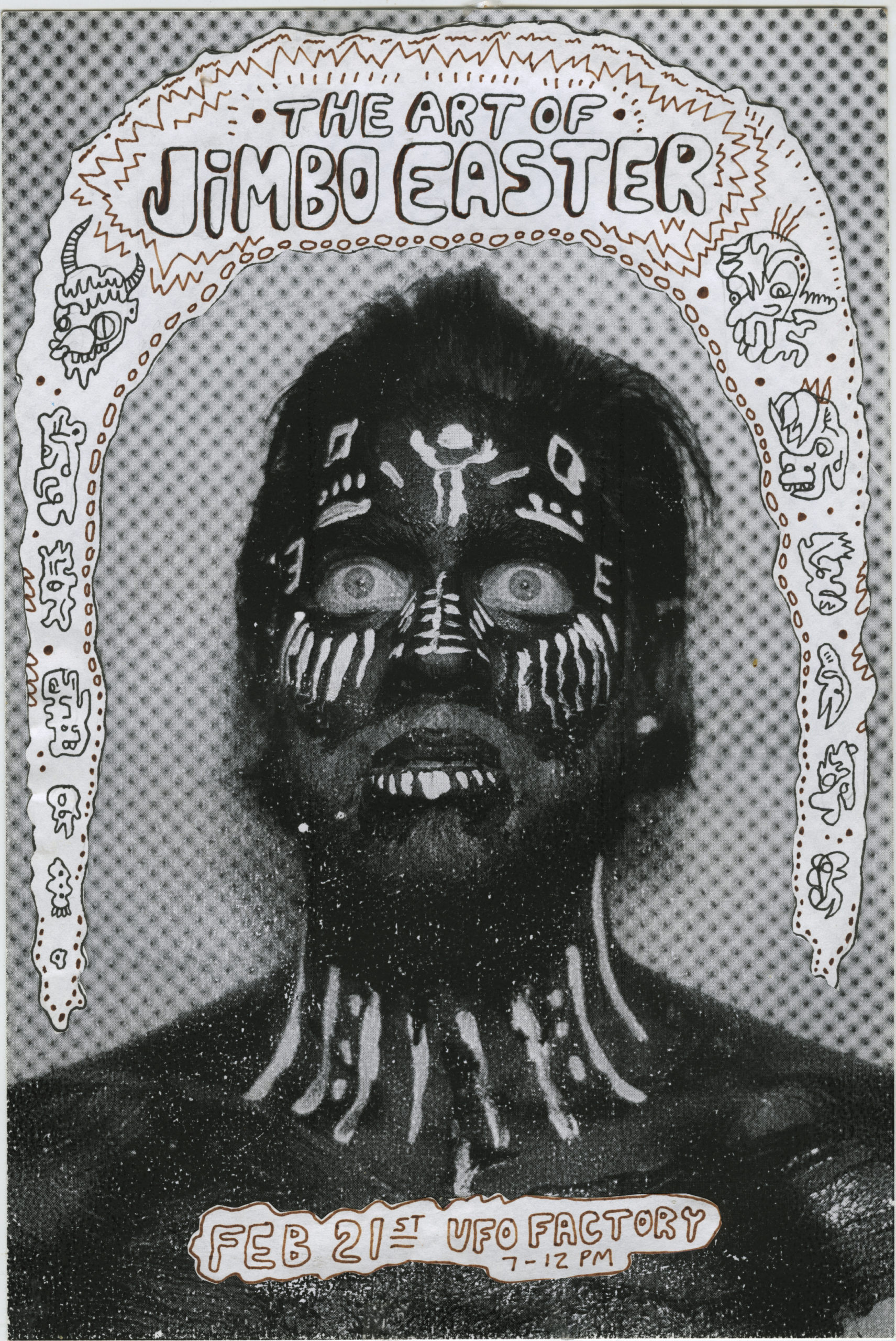

Jimbo Easter, born James Millross, is a multi-disciplinary artist with an eccentric imagination and relentless energy. Moving between drawing, sculpture, sound, film, and body performance, Easter embodies innocence, humor, and a distrust of the overly technological. The discipline behind the chaos is nourished from years of construction work and a twenty-year art practice. Easter is an outlier without any agenda or brand to sell. He creates unique hermetic worlds with their own strange logic. A descendent of Alfred Jarry, Lost in Space, and Gumby, he is part flowerchild, part anarchist, and part Time Machine Morlock.

Born in 1975, Easter’s childhood home was in the run-down Brightmoor section of Detroit, where “the wooden slats of floor in my bedroom didn’t come together,” Easter recalled, “and the rats would reach their little hands between the slats—scratching little rat hands. It was one of my earliest memories—really nightmarish.”1Unless otherwise indicated all quotes are from recorded interviews or email correspondence with the author. Parts of this work – part oral history, …

The Millross family grew and moved to Redford, a working-class suburb. Easter is the eldest of his siblings: brother, Levon, a clothing designer, and sister, Melissa, a photographer. “My parents were creative people full of energy,” Levon said. “I remember them always having parties. As kids we’d try to sneak around and get a peek at what they were doing. My dad ruled the basement. He had black light eyeball posters, pictures of Madonna and Prince, and a trunk full of wigs, props, and strange clothing. They would all party down there—dress up in costumes and make weird videos.” The parents’ creativity rubbed off on the children. “Jimbo made drawings and did lots of clay modeling as far back as I can remember,” said Levon, who is six years younger. “We didn't have a lot of money growing up, so we created things out of whatever we had as a family. Our dad put on these mini performances when Jimbo and I were kids—just to be weird and make us laugh. I think our creative energy comes from our dad, but my mother was my main source of inspiration.”

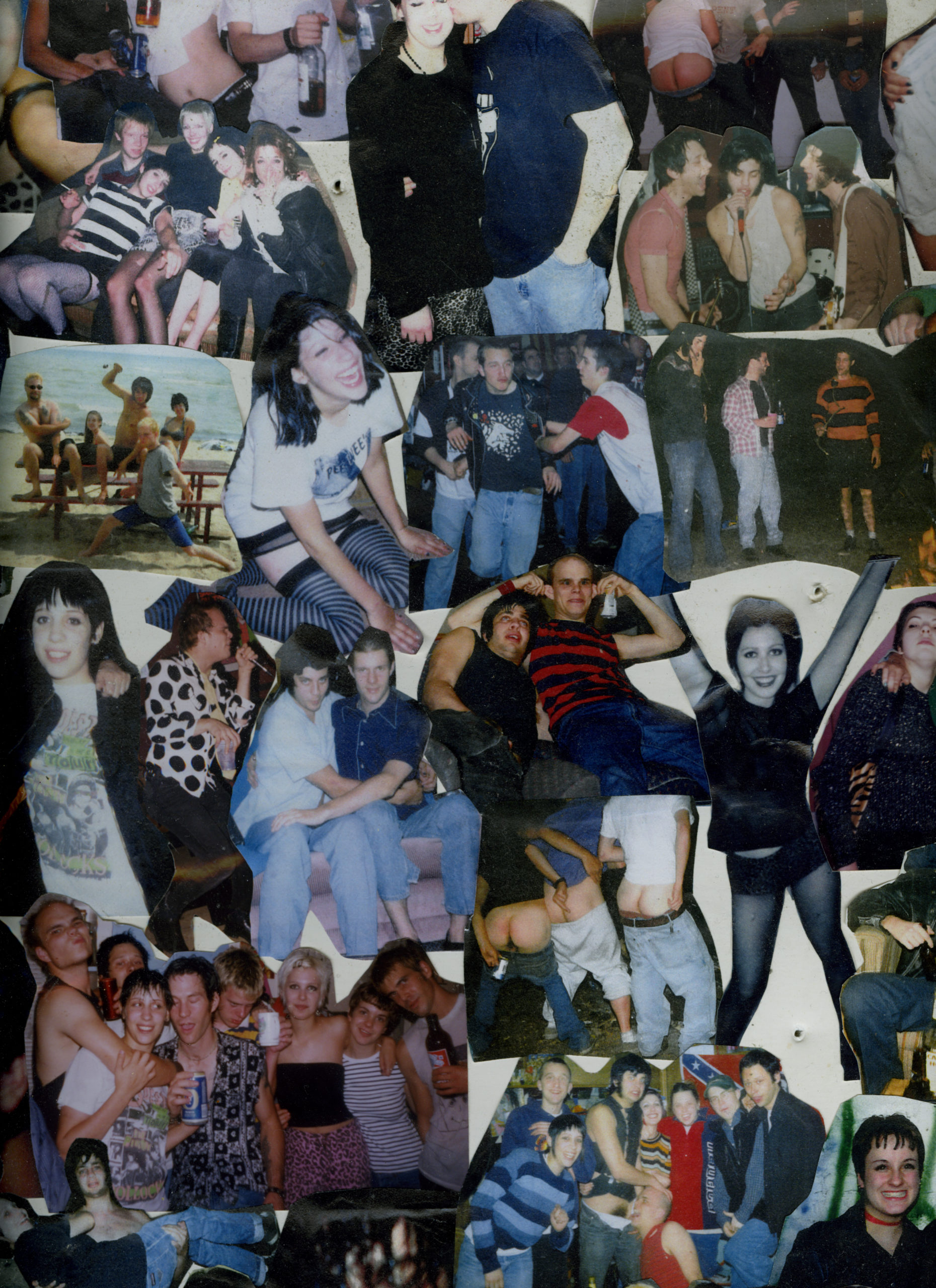

As a Redford High teen, Easter took up cutting himself. His earliest performances and “cutting parties” happened in his parents’ basement, blending hard-core punk with his private theater of pain: “I’d get together with a couple of my tight friends and we’d have these razor parties and get really loaded [and] at some point in the night we’d bust out glass or razors and start carving up really hard,” said Easter. “Just total bloodshed—and we’d do it privately. I did it too much, enjoyed the ritual of it. Eventually I phased out of it and quit when I was 28.”

Easter’s invitation-only performance parties grew into complex sets and routines. “They started just after High School around ‘95 or ‘96. I built these small sets, like little cartoons,” said Easter, “I built the full front end of a truck out of cardboard. The performance started with me being inside of the truck, moving into a full crucifixion scene. My friends would all be playing live music and some people would just be sitting on the floor watching it. I mixed my friends together, trying to do things we wouldn’t normally do.”

The basement parties had a lasting effect on his brother. “Those performances are imprinted into my memory,” said Levon. “I’ll spare the gory details and say it was something people hadn’t experienced yet and definitely opened our minds and made us realize my brother was going somewhere nobody around us was ever gonna dare to go. Viewing this at a young age was something I just accepted and understood as part of his journey to fuller self-expression. I miss those days of all the parties and performances in my parents’ basement. I spent most of my time down there—as a kid it was a cool place to be.”

Easter has a close relationship with his counter-culture parents and said, “They were a big part of the music scene in Detroit. They hung out and went to all the shows—unlike most other parents. They became friends with all my friends.” His father James Millross was self-employed as ‘Jumpin’ Jammin’ Jimmi’s Jive Productions,’ performing weddings and other events as a DJ with a full time residency at Detroit’s Seagull bar where his mother worked as a coat-check girl. Millross would also later perform in some of Easter’s improv bands. “There was a distinct rebellion he had when he came of age,” said Easter’s wife Jennifer Price, “He’d been around so much wildness as a child that he felt responsible as a teenager.” Easter took on steady work in construction and developed a stable home-life, mixed with his duality of a wild lifestyle producing art. “I became a parent to my parents,” added Easter.

Easter and his music fanatic crew hung out at the Record Collector in Livonia—an independent store stocking hard-to-find experimental music. “My dad would take us there literally for hours,” said Levon, “I remember all the bootleg concert videos and the burning incense. It was the start of a musical journey for all of us. My dad traded records and CDs there and we’d stop at the Mouse House [a head shop and poster store owned by Stanley ‘Mouse’ Miller] on the way home. All the little punks we knew went to the Record Collector.” Davin Brainard, a noise music aficionado, worked at the Record Collector from 1988 until 2001 and recalled his first meeting with Easter: “Jamie and his pals used to come into the store—we met in the early 90s. My first memory of Jamie was of me telling him ‘Cool Frankenstein sweater!’—his sweater had huge holes in it and was patched with thick yarn stitching, Frankenstein style. We became friends.”

Princess Dragon-Mom (PD-M) was a pure noise band born in the Record Collector around 1993. Kenny “Mog” Greenbaum was employed there and spoke of its early days: “Davin and I got together during work,” said Mog, “There was a long narrow concrete hallway in the back of the store—dark, smelly, and harsh. We got two amps, some distortion pedals and started bashing away. Warren Defever (His Name Is Alive) started to join in and PD-M was born. Davin introduced us all to Japanese noise.” The first PD-M show was in 1993, backing up the Boredom’s first tour at Todd’s in Detroit. Early PD-M shows featured loud sustained feedback, jazz style drumming, giant cardboard props, and semi-violent antics. Mog’s main instrument was a menacing piece of bent steel rod he held in both hands with a large cracked cymbal in the center. It was played by smashing it onto the floor and walls. He called it the “Mecca Wheel.”

Mog had a deep affection for M-80s, one of the loudest firecrackers you could get. “I had an arsenal of machines and noise generators to produce various sounds,” Mog said, “but I liked the idea of small explosions at our performances. I used to light M-80s off when the opening band was playing—to startle and rattle ’em. It introduced a sense of uneasiness. One memory was with PD-M and Godzuki playing at Rick’s Café in Ann Arbor. That night I lit a box of M-80s off in the dressing room and stayed in the room. I crouched on the floor, head between legs, and boom! A huge flash of light, it shook the room and blew the door shut. That same night I destroyed the floor at the cafe with the Mecca Wheel, but that’s a whole other story. The fire department was called, and Bob from Car City Records was there. He came to my aid as the club bouncers and management wanted to hang me. Bob was yelling at them, “He’s an artist, he’s an artist…”

Defever’s Time Stereo studio was set up in his childhood home in the quiet suburb of Livonia. Masses of cables stretched from the first floor to the basement, where bands recorded. Brainard resided in an upstairs bedroom with his massive record collection and Ultraman figurines. The Time Stereo house became a nucleus of noise and art; a scene that fed into Easter’s imagination. He was a regular.

Timmy Vulger (Clone Defects, Human Eye, Timmy’s Organism) became friends with Easter at their mid-nineties meeting at an oldies concert sponsored by 104.3 FM. “It was the beginning of a beautiful friendship,” said Vulger. “We had the same favorite Misfits song: Bloodfeast. We'd hang out in his parents’ basement weekly or every other weeknight; listen to music and drink.”

Easter’s psychedelic basement/bedroom was one of many spaces he’d transform. “It was decorated floor to ceiling with weird Japanese toys, drawings, and punk posters,” said Vulger. “It was an inspirational colorful cave to drink, get high, trip, play music and listen to music in. Many of the greatest parties of my lifetime went on down there. I quit a ton of weekend cooking jobs just to go hang with the ‘Drunk Battalion.’ One time we took acid, got drunk and trashed some greens at a golf course in the middle of the night. Got home and he made some insanely spicy fish that I’ll never forget. We still get together as much as we can, make art, shoot the shit and listen to music—just like ole’ times.”

Easter and Vulger fronted several different bands while developing intense stage shows. “Abusing ourselves on stage made sense,” said Vulger, “The music was angry and we were angry; smashing mics to our craniums, cutting ourselves with broken beer bottles, throwing ourselves into the crowd. Maybe we were trying to out-do each other in a ‘healthy/unhealthy way,’ so to speak. Easter had two really great bands before the Piranhas: Jim Beam and the Throw Ups and the Cigarette Burns. I tamed up a tiny bit after the Epileptix broke up when I formed the Clone Defects. Jimbo just got even wilder with the Piranhas—best live band in the world since the Stooges and early Alice Cooper. Piranhas and Clone Defects were a gang, we were brother bands, but we sounded completely different. As different as the Stooges are to the MC-5 or the Germs are to CRIME.”

The Piranhas were an extreme art-damaged and hard-core reaction to the exploding local garage-rock scene fueled by the success of the White Stripes. The Piranhas played short, furious sets. “It was a complete frenzy from beginning to end,” said Easter, “I liked the way I felt at the end of a show—when I’m keeling on the edge. That’s what I’m exploring now in performance. I just get there in a different way, on my own terms.” The Piranhas had a difficult reputation earned by their outrageous stage act, and were banned from most Detroit area clubs. Easter exploited this with public stunts—once duct-taping a dead rat to his chest during a gig at the Gold Dollar. Every performance was grotesque theater—a chance to incite the audience (and the band themselves) into maximum frenzy. Vulger witnessed many Piranha shows firsthand. “One time he made the Glove of Danger,” said Vulger, “It was a Nintendo power glove he modified into his own self-abusive weapon. He put razor blades on each fingertip, hot glued garnishes of broken glass on the top and bottom of the palm then painted it brightly in a vomit-variety of colors, Jimbo style. The show is all on VHS. I filmed it. It was the Piranhas first show in Ypsilanti. Two songs in he puts on the Glove of Danger. Quickly he caresses his torso and arms with the glove! He slices his forearm open (it was fucking deep!). He looks into the camera and says, “I gotta go to the Hospital!” Vulger also saw the infamous Piranhas at the Gold Dollar show and said, “Toward the end of the set Jimbo took out a dead rat and started smashing its head with a hammer then electrical taped it to his torso. Ian Ammons started smashing his hollow body guitar all over. The crowd (our gang of punk friends and I) threw stacks of the weekly newspaper all over the bar until the place looked like the inside of a papier-mâché piñata! The bystander garage rockers thought it was a live rat that was murdered so they immediately walked out in total fear and disgust. That was THEE GREATEST ROCK N ROLL SHOW I’D EVER WITNESSED. I don’t think Iggy has ever come close to putting on that kind of show.”

The Piranhas had an elaborate tour of the West Coast sponsored by their label In the Red. “It was all paid for,” said Easter, “The label flew us out, so we did the tour—it was totally insane and violent—tons of hallucinogens. Three of us in the band burned the candle hard.” At the Hemlock club in San Francisco, an audience member threw a highball glass at Easter, shattering on his face. The bleeding was profuse and he was rushed to the hospital, receiving multiple stitches around his mouth and gums. “The audience was being really feral,” said Easter, “my face was falling off and I thought ‘Is this what they think it’s all about?’ but I finished the rest of the tour in stitches with my face all redone and swollen—and I had to take this lockjaw medication, because I was cut with a dirty bottle.” At the next show in Los Angeles, an audience member climbed on stage and tried to pull Easter’s stitches out. “I just took the microphone in my fist and smashed him across the face, knocking him out. He fell to the floor like a wet noodle. After that tour it was just like, hey, I don’t want to do this anymore. I’m not your little fucking circus animal. And I quit. I just walked away from it. And it was doing really good, but in that band I got hurt a lot. I did mix a lot of self-abuse into the live band shows, but the performances got more powerful when I started to do solo shows.”

After leaving the Piranhas, Easter helped form other freak bands, including: Odd Clouds, Blood Accordion, Druid Perfume, Moonhairy, Crumbs as Boulders, and the Free Moon Family. Each group had their own unique origin story and mythology, becoming part of an Easter chain of theater/sound troupes. Odd Clouds played free-jazz/psychedelic noise-rock and were all devoted improvisers. “I began playing percussion in Odd Clouds and did that for a couple years,” said Easter, “It was an eight-piece freak group that began with me and Chris [Pottinger] wanting to do something a little different. Any friend of ours who could play an instrument was a member. It was great training, learning to play on the fly like that all the time. You have to just do it to know what it’s about.”

Odd Clouds formed in early 2000, at a large house Easter shared with friends. The house sat on the fringe of Hamtramck, beside the I-75 highway surrounded by abandoned and burned-out homes. Artist/musician Chris Pottinger (Cotton Museum, Odd Clouds, Sick Llamas) began his label Tasty Soil at the house. “I first met Jimbo after doing a Cotton Museum set at Noise Camp outside the C-Pop art gallery in Detroit,” said Pottinger, “I think the Piranhas played that night too. We had a mutual love of drawing mutants and traded some art through the mail. After playing more shows together in Detroit we decided to do a West Coast tour with our solo projects. I remember playing a house show in Olympia, Washington. Jamie insisted on doing his performance in the bathroom where he was playing a trombone without any clothes, perched on the edge of the bathtub filled with water. He pissed in a cup, drank it, puked and then stapled his legs with a staple gun all while uttering some sort of crazed chant. I remember it completely weirding out the ten or so people in attendance.”

Pottinger recalled their Hamtramck art-house days. “Everyone living there was constantly working on all sorts of weird projects: recording, drawing, making short films and playing strange records […] Jimbo and I both shared the upstairs area, and Heath Moerland moved into the lower floor shortly after I moved in. The house started to feel like a commune after our band started practicing and recording in the attic every other day. We spent the most time working on Odd Clouds together, releasing three LPs, a 7 inch, some CD-r’s and a handful of cassettes. Heath (Moerland) and I would record our electronics and reeds duo, Slither, down in his place. I was drawing and recording my solo electronics project, Cotton Museum, up in the corner of my zone. After cleaning out the moldy, trash-filled basement, we started putting on gigs in that dungeon. We dubbed it the “Get Lost House.” We had a bunch of shows there, but somehow never had any problems with police shutting them down.” Easter remembered an inspirational mushroom trip with Vulger at the Hamtramck art house. “I made a bunch of drawings in advance of the trip,” said Easter, “and we spent some time looking at artwork around the house. I remember looking at the drawings and seeing the lines come alive, crawling like maggots on the page. After tripping it allows you to have insights about people - it brings you closer to the people around you.” As the neighborhood was collapsing, Easter took his solo act to the audience, performing guerilla style for small groups around the city. Music provided a stage for Easter to try out various actions on his body and test them on an audience. This led to complete self-reliance, opening the door for solo performance.

Antonin Artaud created one of the first manifestos for experimental theater, performance art, and the public body in extremis. In The Theater and Its Double, Artaud wrote: “We use our body like a screen through which pass the will and the relaxation of the will.”2Antonin Artaud, The Theater and Its Double (Grove Press, NY, 1958), 138. No performance art or contemporary theater exists without a nod to the Theater of Cruelty as conceived by Artaud or his theories of performance. By invoking a transgressive solo theater, Easter taps directly into Artaud. Easter’s hypnotic performance rituals have parallels in other children of Artaud; Viennese Actionist Hermann Nitsch; Meat Joy artist Carolee Schneeman; the squirting fluids of Paul McCarthy; the Cut Pieces of Yoko Ono; the provocations of Marina Abromović; “Super-masochist” Bob Flanagan, and the theatrical orgasmic soundscapes of John Duncan. Many of these artists combine sound with a distressed body. Another more overt reference is the self-mutilation and no-limits attitude of self-proclaimed punk rock ‘savior’ GG Allin, who wrote from his prison cell: “We must live for the Rock 'N' Roll underground. It CAN be dark and dangerous again. It CAN be threatening to our society as it was meant to be. IT MUST BE UNCOMPROMISING.”3GG Allin, Prison Manifesto, 1980, https://www.scribd.com/doc/70766155/GG-Allin-Manifesto.

In solo performance, Easter often re-purposes common household items for props. These are used in abusive, painful, self-humiliating ways. Objects from the dollar store or handyman tools have their normal uses overturned in Easter’s skewered reality. His props become symbols of rebellion, bondage, torture and pain—the same kinds of tools used in his day job in construction. During performance Easter often enters a deep trance-like state. The audience is kept on edge, a quiet accomplice—or as uneasy voyeurs watching an intense personal ritual. Barriers of stage and direction vanish. Many early performances took place in garages, abandoned houses, attics and basements around the city, small spaces liberated from friends and relatives. In his performance Surgery (2005), Easter took a razor to his leg, opening an ugly 8-inch gash. “I did a surgery on my own leg,” said Easter, “I cut my leg open and poured whiskey over it—then I held it shut and with a staple gun sutured the wound.” His future wife, Jennifer Price, researched natural blood coagulants before she came, bringing cayenne pepper to help stop the bleeding. A Measure of Complete Control from 2009 was held at Cleopatra’s gallery in Greenpoint, Brooklyn. “That was based on milk, blood, and alcohol and we were dressed all in white,” said Easter. “That was a very physical performance. It took me out of my head for a little bit. It was performed for about 20 people and began with me at a table and a guitar drone. It commanded complete silence. Nobody made a sound. I was rolling my fist and face in glass, dripping my blood into a pan of milk. Glass was embedded in my face and hands.” Easter’s body is a bruised painting. He’s often slammed against the floors and walls of his performances, taking on pain and stretching his limits of endurance. He works with immediate sensations and his brief narrative outlines are kept simple. “When I have control of it,” Easter says, “I feel like I’m forcing myself through these weird corridors, which I don’t necessarily want to go through.”

There is the feeling of a score in the performance, yet none could be recreated without Easter himself. The works are often challenging and dangerous. It’s like Houdini without any tricks. “I think it might be to test his own mind and the audiences, to see how far he can go, to make the onlookers feel uneasy,” said Vulger. “I think sometimes he even makes himself feel uneasy. He once stapled his butt cheeks. That's hilarious, original and un-easy to do! As crazy as he’s gotten over the years, I’m thankful he has survived.”

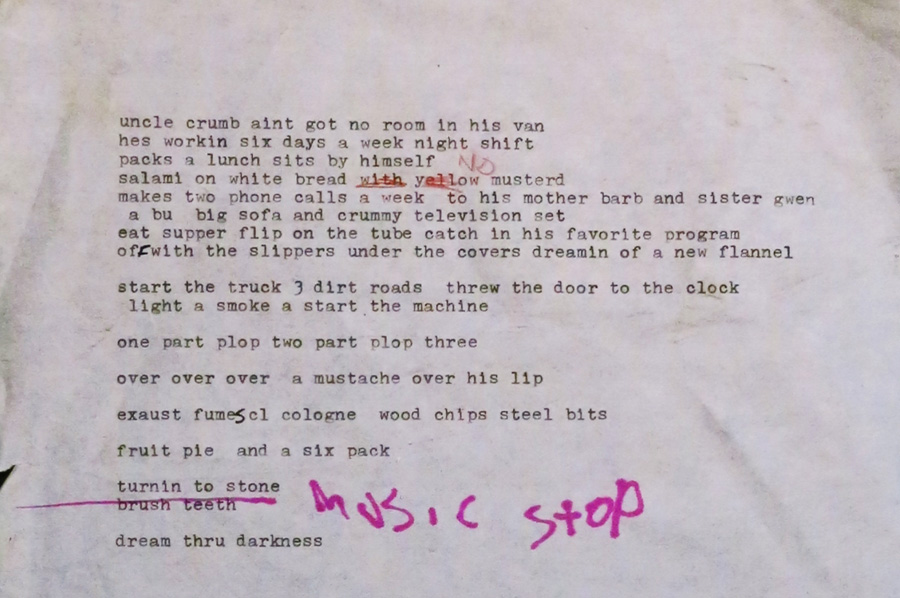

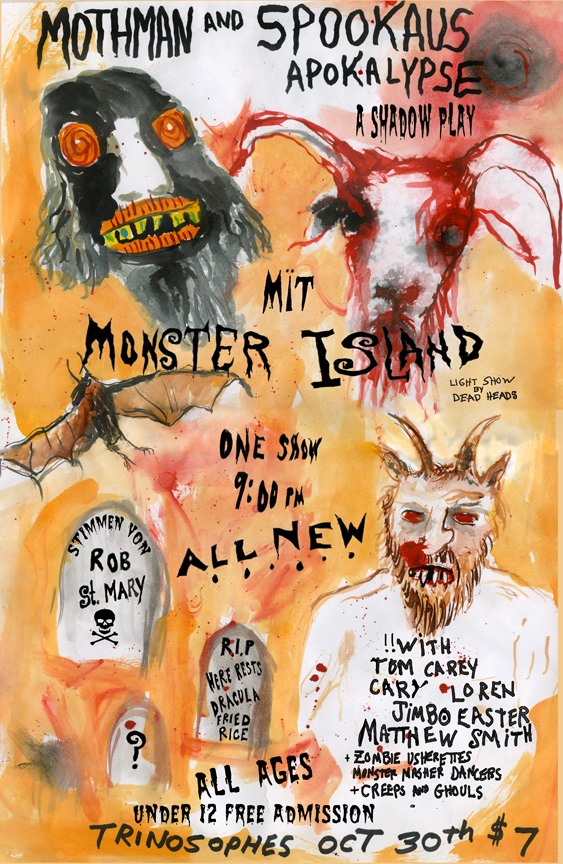

Sound is used by Easter as background texture and a diving board—a way to enter the work. “I often go into a trance-like state when performing,” said Easter, “The music is like incense—it creates an atmosphere and gets me into the mood.” In The Living Word, 2011, held at Public Pool in Hamtramck, Easter played the role of a southern preacher during the rapture: speaking in tongues, muttering in glossolalia beside the music, acting Timothy Carey’s messiah/rock preacher role from The World’s Greatest Sinner. These incantatory rituals are recurring themes. Cat Shit Mountain from 2012, was a return to Easter’s childhood. Recreating scenes in choreographed tableaux, Easter costumed the musicians in bizarre masks, playing space sounds as spastic dancers joined in, a three-hundred-pound human cat was digging in a giant litter box, businessmen had lunch, and a large spread of junk food was assembled on tables. Easter crawled on stage, with an alley-oop in a cave-man outfit. “We did a gluttonous performance,” he said, “we had a whole smorgasbord of grotesque food: candy, peanut butter, white bread and vats of lemon juice and punches. I was trying to see how much sugary, gross food I could eat.” Price assisted in the performance again. “He gave us each ten tasks to do with the food,” she said. “I had to dip the carrots into liquid, then draw something on the bed. Another task was to place the slices of bread onto different things.” An Easter performance usually begins quietly, telling a familiar story in a recognizable setting, and slowly it gets pushed into reverse, ending in a surreal torrent of destruction or self-mutilation.

It is nearly impossible to piece together the records for all of Easter’s performances or sound recordings. Many of his best works happened anonymously in garages and basements for a few friends, and documentation has been spotty.

During his time at the Get Lost House and inspired by horror films, Easter began making sculptures of bizarre creatures heavily detailed with clay, hair, artificial blood, and found objects. Easter left the disemboweled things around the house to shock visitors. “One time, Jamie and I fashioned some sort of diseased looking dog-beast out of old faux-fur coats, hangers, pillows, tape and modeling clay,” said Pottinger. “It looked pretty realistic, like some special effects from a Toxic Avenger film. We squirted oil and Ketchup on it and set it out on the corner sidewalk. I remember laughing, watching from the shadows up on our balcony. People would cautiously walk up, poke it with a stick and then run away fearing that this Hamtramck mutant would attack them.” Easter would almost lose his construction job over a bloody rat sculpture he left on the office floor. “I was into making things that would deceive a person,” said Easter. “It’s about creating an illusion. I brought this mutilated rat to work and almost got fired. My boss’s wife found it and called my phone 40 times, freaking out, hysterical. I just said, ‘Why don’t you touch it—I made it.’ I really like making things—the challenge of it—but another origin of making these was when I actually saw a dead animal rotting on the roadside. I couldn’t stop to take a picture of the creature and was transfixed. No artist could make something like that. It was just so beautiful.”

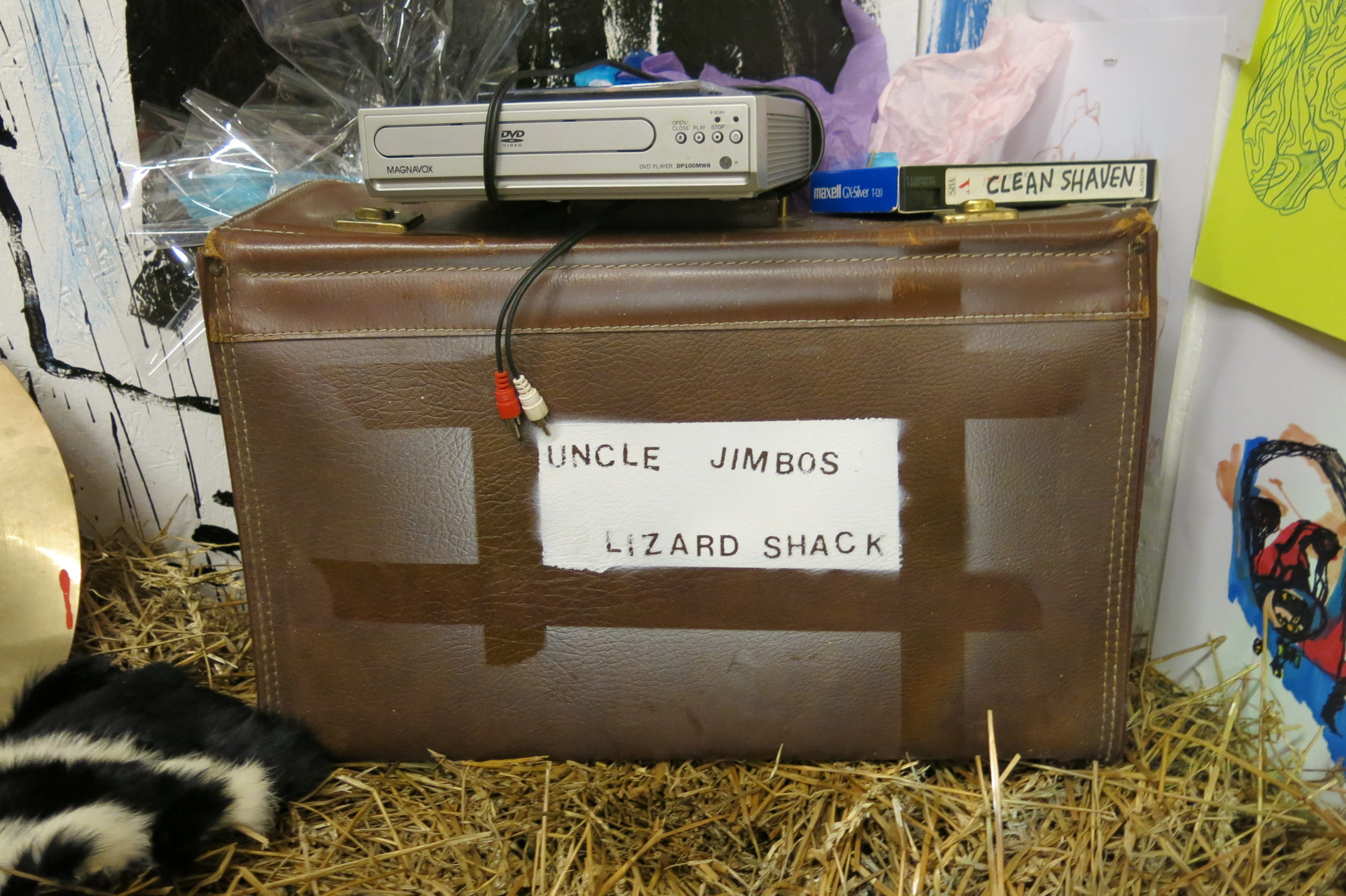

Easter’s diorama constructions and film projects led to other projects bringing together a variety of sculptures: totems, hand-painted wooden plaques, alien figurines, and carved self-portraits began to appear. Sculpture has a close relationship to music and is related to installation art—an area Easter has been slowly engaging with.

Easter’s home studio is a garage and large room addition attached together at the backside of his house in Royal Oak, Michigan. Resembling a life-sized version of his dioramas and shadow boxes, the busy space is filled with electronics, tape-recorders, percussion instruments, and projects in different stages of development. It’s here in the studio that Easter develops his tiny worlds. Easter’s visual art is equivalent to the music: spontaneous, improvised, dramatic, and colorful, with a Raw Vision brutalist quality. “The artwork never came together as it has recently,” said Easter, “I’m not afraid to be funny, and was a little too serious when I was younger. Now I can appreciate being the fool. I don’t have any shame.”

Filmmaking is an extension of Easter’s art. Working out small dramas and animations is a challenge, one influenced by the humor and wizardry of Jim Henson, the whimsical style of Gumby animator Art Clokey, and the dark organic alchemy of H.R. Giger. Easter mixes ideas of the folkloric and futuristic with a psychedelic touch that recalls the apocalyptic gardens of southern folk-artist Howard Finster. Building on a similar primitive style, Easter creates distinct three-dimensional personalities and characters, a talent more commonly found in animators and cartoonists.

Bogglewart Forest from 2005 is a puppet diorama—a color saturated universe and a short video made with the help of Brainard. Bogglewart Forest is a magic land of jeweled trees and outer space flora and fauna, populated by space trolls and buck-toothed bearded gnomes. The soundtrack of beeps, tweets, and high-pitched munchkin voices wraps the narrative in fanciful tableaux. “Bogglewart Forest is our best collaboration,” noted Brainard, “Jamie made the set, wrote the story and was chief puppeteer. I was the cinematographer, cameraman, and did the editing with Jamie.” The Secret Land of If (2006) was one of Easter’s most complex and heavily detailed dioramas. This coffin-sized black box was a tunnel vortex filled with hand-painted neon creatures—a glow-in-the-dark black-light fantasy forest. The Secret Land of If had its own ecology similar to Bogglewart Forest, but was made to be viewed through a plastic distorting lens at the narrow end of the box. Designed for one person to experience it at a time, the work was a psychedelic step-child to Joseph Cornell boxes, Marcel Duchamp’s Étant donnés, and the antiquated mystery of Edward Gorey’s accordion book, The Tunnel Calamity. The Secret Land of If came with its own soundtrack and miniature light fixtures, transporting the viewer into a glow-in-the-dark illuminated paradise.

Easter is a craftsman and bricoleur devoted to illusion. “There’s a lot of careful construction going on. I’ve been building things since I can remember,” Easter said. His favorite sound-making tools are acoustic, percussive, and analogue. “For the last couple years, I’ve been making these homemade instruments,” he said. “Using sheet metal and contact mics, I’d screw bells and metal onto these wooden planks and play them electrified or acoustically.”

Easter markets his work directly with collectors and takes commissions. There are enough small labels to fill his musical output. “I tend to have a long backlog of projects and jump from one tiny label to another,” he said, “There’s always someone putting new stuff out.”

For the past eight years Easter has hosted a gathering of fellow musicians—an annual mid-summer tradition he calls the Dune Jams—an event with an impossible-to-read-map to a secret location on a stretch of sand dunes at Island Lake. People are encouraged to bring instruments, noisemakers, and food for a day of music and frolics on the dunes. “When we first scouted the area for Dune Jam,” said Easter, “We found this area that formed an almost perfect bowl, and it had these wonderful sound qualities, like a natural acoustic echo chamber. Then we wanted to play on the edge of the dune, and climbed up with all our equipment, and on top of the dunes the sound was even more amazing, it carried for miles.” Brainard added, “I’ve been at every Dune Jam. They started small, like ten people, but soon became too big to survive. People at the park said, ‘they’re all on drugs,’ but we weren’t. We were just being free on a hill in the sunshine.”

Easter’s collaborations with artist Johnny Prey began after a trip together in northern Michigan. “My history with Prey goes way back,” said Easter, “He was an old friend, quite a bit younger and originally from this area. Johnny now lives in Los Angeles but when he was last in Detroit a few years ago we worked on a film together. We don’t see each other too often and I just said to him, ‘Let’s make a damn movie right now.’ So, we pushed ourselves and in one day we made this film in a barn in my backyard. It must’ve been ninety degrees outside that day and what we came up with was mind-bending. I always feel that when I come up with something good—it damages me in some kind of psychic way. I just lose a little bit of my soul. And that performance—the piece we did together was the first part of the story.”

“I had been dreaming about collaborating with Jimbo for many years,” Prey said, “We were out camping and had eaten some mushrooms and we wandered deep into the north Michigan woods. We stumbled upon a camp of two gay hillbillies who wanted us to look at this weird thing they found and killed in the woods. I didn’t know what the hell that thing was but it looked like alien road-kill! They gave us sticks and we all poked at [it]. They asked if we wanted to eat with them as they said they were going to BBQ it in our honor. We politely declined.” This woodland encounter inspired the script Lawn People, written by Prey. Easter recreated the creature in his garage. Describing the piece, Prey said, “It had a tail, fur, and even bulbous alien sacks that breathed when you blew into tubes fastened to it!”

Prey invited Easter to create a performance with him at Coaxial Arts, a video co-op he helps run in Los Angeles. “We decided to make it a dual performance,” said Easter, “Prey opened, I closed, and we showed some films in the middle. I was really happy with it. The piece was live in front of an audience and I just went deep into my head with it. I was in a complete trance.” Easter put together a soundtrack on cassette tapes for the performance. “I’ve always been into manipulating tapes,” said Easter, “stretching them, over-layering, creating sound collages with different speeds. After that show I was completely wrecked and just crawled back into bed and got super quiet.” Prey said, “What I love about Jimbo's performance style is how chaotically controlled it is. For example, the day of the show, with about five hours ’til we needed to prep for the show, we walked along the Venice Boardwalk in Venice Beach, observing the freaks and lost hippies smiling at us, and it was so peaceful. We laid on the beach and talked for a while before we jumped into the freezing ocean. Afterwards Jimbo says, ‘Hey let’s head over to the Dollar Store by your house, I need to get some stuff for the show.’ In ten minutes he conjured up a ritual with food dye, a metal bowl, clothespins, gloves, electric tape, and some rat traps. It was very inspiring. He was saying, ‘Don’t overthink it, let the chaos be an organism that lives by instinct.’ Jimbo’s character, Salvador, reminded me of a Kabuki Rice Farmer. His pre-recorded sound track was like an Alan Lomax field recording of extraterrestrials.”

Easter and Prey are plotting a return engagement at Coaxial Arts. Direct contact with an audience is key to their practice. “I’m really interested in going on tour by myself sometime,” said Easter, “Just to go in my truck and do performance art around the country for a few weeks.”

*

Around 1950, Cage used the I Ching and threw coins to compose Concerto for Prepared Piano and Chamber Orchestra and Music of Changes. The hexagrams of the I Ching were thrown by chance and transposed into music staves to determine the composition. These early cut-ups opened a utopian paradigm for Cage, combining chance operations with tape collage, radios, electronic instruments, prepared pianos, vocals, drone sounds, and noise. These dynamics of composition helped expand the vocabulary of music influencing the happenings of Allan Kaprow and the drone music of LaMonte Young.

*

Cage’s life-long dream was to record the sound of mushroom spores as they were being released. In his biography of Cage, Begin Again, Kenneth Silverman comments that “Having long desired to hear every sound, he wished to apply technology so as to hear the mushroom itself as it dropped spores on some surface.”6Kenneth Silverman, Begin Again (Knopf, New York, 2010), 166. In 2013, at the Barbican Art Gallery in London, a new version of Cage’s tape composition, Fontana Mix, was performed using bioelectrical recordings taken from living mushrooms attached to oscillators. Created by “sound ecologist” Michael Prime, the work was one of the first bio-music compositions created for the microphonic amplification of mushroom spores.

*

Mushrooms are the reproductive fruit of blackened, networking threads of underground fungi feasting on ruins, living off decaying trees and roots, and breaking down organic matter in their final stages of existence. Mushrooms transform decay, enriching the soil. In the groundbreaking book Mycelium Running, visionary mycologist Paul Stamets demonstrates how mushrooms could help save the planet by digesting and decomposing toxic wastes and pollutants.

*

Amateur mycologist and science fiction author Frank Herbert admitted during an interview with Stamets that his epic novel Dune (1965) was inspired by psilocybin. “Frank went on and told me that much of the premise of Dune—the magic spice (spores) that allowed the bending of space (tripping), the giant worms (maggots digesting mushrooms), the eyes of the Freman (the cerulean blue of Psilocybe mushrooms), the mysticism of the female spiritual warriors, the Bene Gesserits (influenced by tales of Maria Sabina and the sacred mushroom cults of Mexico)—came from his perception of the fungal life cycle, and his imagination was stimulated through his experiences with the use of magic mushrooms.”7Paul Stamets, Mycelium Running: How Mushrooms Can Help Save the World (New York: Ten Speed Press, 2005), 123. Dune is also one of the first ecology novels, a parable about a future world that’s become a desert, and where underground water is a coveted secret source of wealth. A transformative book of the ’60s, it was prescient not only about ecology and climate change, it explored global transformations and the mind-body connection.

*

Gordon Wasson (1898-1986) was a writer-researcher and father of ethnomycology. He studied the ancient Vedic use of Soma, developing a theory that mushroom cults were the origin of human language and religions. Wasson was indoctrinated into the Mexican mushroom cults by Maria Sabina, publishing his account in the May 13, 1957 issue of Life Magazine, an article which influenced Timothy Leary’s study of psychoactive drugs.

*

According to the theory of Panspermia, it’s thought that life is distributed throughout the universe by organic spores buried inside meteors, asteroids, and possibly spacecraft. The spores of mushroom Fungi are microorganisms that can survive and exist as space dust for millions of years, releasing themselves into the air and water under the right conditions.

*

A single mushroom can release millions of spores, spreading itself out into a large underground network. In 1988, the largest living organism on the planet was discovered, spawned by a single fertilized spore; it is 1,500 years old, weighs 220,000 pounds and is a forty-acre fungus still growing near the city of Crystal Falls, on the western edge of the Upper Peninsula in Michigan.

*

Terence McKenna (1946-2000) was an expert on psychoactive plants and studied the psilocybin mushroom. McKenna believed the mushroom’s unique DNA structure was extraterrestrial in origin. Nothing with a similar chemistry exists in the natural world. He postulated that the psilocybin spore was a space messenger—a replication of spores from an alien species that came to Earth, to spread telepathic communication.

*

McKenna traced the human use of psychoactive mushrooms for thousands of years and likened their effects on consciousness to a connection with the cosmos. McKenna believed the psychoactive plants he discussed in The Archaic Revival offered civilization its only hope: “It connects you up with the real network of values and information in the planet. The values of biology, the values of organism, rather than the values of the consumer.”8Terrence McKenna, The Archaic Revival (New York: Harper Collins, NY, 1991), 13. Mushrooms were a spark that introduced us to language, religion, and consciousness—they are what made us human, argued McKenna.

*

Art of Noises, a 1913 futurist manifesto by Luigi Russolo, proclaimed noise was born with the birth of machines. “We must break at all cost from this restrictive circle of pure sounds and conquer the infinite variety of noise-sounds,”9Luigi Russolo, The Art of Noise (Futurist Manifesto, 1913), translated by Robert Fillou (New York: Something Else Press, 1967), 11. wrote Russolo. Urban expansion created new sounds that led Russolo to design noise instruments he called Intonarumori, which he felt would expand the vocabulary of music. The link between Russolo, Cage, and contemporary music can be traced through the diversity of sounds created through technology.

*

In the world of acoustic sound, no work is more futuristic than Satie’s mystical Vexations of 1893, a piano work of unstable music consisting of tritones that never resolve harmonically. The work is played slowly and performed 840 times, taking roughly eighteen to twenty-four hours to perform. To know one solitary piece until exhaustion is an exercise in Zen thought. One theory suggests Vexations was Satie’s reaction to the excessive, bombastic, hyper-melodic Wagnerian operas. In 1963, seventy years after it was written, Cage organized the first live Vexations concert in New York City with 12 pianists (one performer was John Cale of the Velvet Underground).

*

Technology-based noise is often performed in a distorted, sampled, and non-rhythmic way. Noise dismantles music by shredding technology—abandoning data and pure sounds. Analogue tape recorders, gestural vocals, feedback, and junk equipment are common tropes with noise artists. Electronic music is often masked in a self-reflexive, ironic way of performing, composing, and improvising.

*

Bonds between music and visual art can be traced to ancient Egypt where the shadows of dancers in performance were reflected on polished marble. In the nineteenth-century shadow theaters of Paris, Erik Satie performed ambient music to images flickering on screen, years before motion pictures. These intimate theaters combined music with visual arts, and were the birthplace of the first avant-garde, bringing many disciplines together with storytelling.

*

*

Brian Eno and Peter Schmidt created Oblique Strategies in 1975 as a tool to assist with music composition. The methodology was a series of cards with Zen-like instructions meant to shake up and move the artist into new directions or follow a more challenging path. Card instructions might say: “(overtly) resist change and (secretly) allow it through a back door.” Or, “Emphasize the flaws.” Oblique Strategies follows other Cageian chance techniques such as the I Ching and throwing dice.

*

After the upbeat decade of Motown and the Grande Ballroom, Detroit fell into financial decline and music incubated underground. In the ’70s and ’80s, noise, punk, hardcore, hip-hop and techno seeped onto the streets, the progeny of Cage’s utopian sound script and Herbert’s Dune. Bankruptcy and urban ruins were the aftermath of failed Fordism. Art slowly emerged, transforming the rotting center, as fungi dissolves dead matter.

*

The Record Collector in Redford, Car City Records of East Detroit, and Encore Records of Ann Arbor supported the local, stocking experimental music and Japanese imports. These were among the few places you could find John Cage and Philip Glass alongside the Boredoms, Keji Haino, Merzbow, Violent Onsen Geisha, and Hijokaidan. Store owners Robert Setlik (Car City) and Warren Westfall (Record Collector) formed the New Music Society in the ’90s with partners Pat Frisco and Brian Callahan, staging live world-class sound and performance art.

*

Local bands such as Princess Dragon-Mom, Godzuki, Clone Defects, Universal Indians, Odd Clouds, THTX, The Beast People, Galen, and Wolf Eyes, were the funky offspring of Cage, protégés of damaged sound and distorted electronics. Most can be divided alongside their respective micro-labels: Time Stereo, American Tapes and Hanson Records. If 1991 was the year punk broke,111991: The Year Punk Broke was a documentary film by Dave Markey featuring Sonic Youth on a European tour. then 2004 was the year of noise, as Wolf Eyes released an album on Sub Pop and toured Lollapalooza with Sonic Youth. The mushroom artists were a tonic of new sound, blooming on the horizon of psychedelic free-jazz.

*

Easter is a human mushroom. His cap-shaped head overflows with spores fermenting and releasing DNA codes into the air. While Easter builds New Detroit in his day job, his art undermines it - turning reality inside out. Easter’s unfathomed art is built on ruins and failure. His visual work embraces mutants, aliens and Lovecraftian mystery. His characterization of the poor southern redneck is both homage and satire. They are worlds of rejection; too lowly, ignorant, and kitsch. With a freak flag soaked in psilocybin, Easter marches his vision forward—an art more about creation than preservation.

*

“Since the ’90s, I always liked to go upstate in Michigan and do shrooms, into the wilderness with friends,” Easter said. “It’s safe there, and psilocybin is a natural high. It begins with a warm rumbling inside, like your whole body is giggling. The surface of things begins to shimmer and glitter, and then you’re tripping. Time is no longer a concern, and your mind is outside it all. You can go real deep inside yourself and connect strongly with the people who are with you. Every trip is unique—and the memory stays with you. You feel yourself connected to the universe.” Tripping is the essence of space travel. A deep connection to nature and the endless space tripping is key for Easter. At a time when natural resources are vanishing, space can be gained by ingesting nature itself. Easter’s preference for sensual experience, action and pure self-expression has kept his mind curious and independent - and against the dominance of human conventions, following the scriptures of Henry David Thoreau’s Walden: “We need the tonic of wildness [...] At the same time that we are earnest to explore and learn all things, we require that all things be mysterious and unexplorable, that land and sea be infinitely wild […] We can never have enough of nature.”12Henry David Thoreau, Walden, Or, Life in the Woods (New York: Library of America, 1991), 255.

*

The film Matango: Attack of the Mushroom People, 1963, is an Ishiro Honda masterpiece with a plotline similar to the ’60s sitcom Gilligan’s Island and William Golding’s novel Lord of the Flies. In Matango, castaways are shipwrecked on a mysterious island, where the only food source is the giant forbidden Matango mushroom that drives the castaways insane—then they each slowly transform into hideous fungus monsters roaming the island. Matango is a metaphor for drug culture, nuclear fallout, toxic contamination, and the weakness of humanity. Asian culture has revered mushrooms as food and medicine for thousands of years, so perhaps it’s no coincidence that until 2002, Japan was one of the few countries where magic mushrooms were legal.

*

Amiri Baraka took notice that SPACE was the connective tissue between Sun Ra and Charles Olson. In his essay “Charles Olson & Sun Ra: A Note on Being Out,” Baraka wrote: “Olson throws out this challenging summary of who and where we are: ‘I take SPACE to be the central fact to man born in America… I spell it large because it comes large here. Large and without mercy.’ Ra and Olson were the perfect mentors for the most advanced artists of the 60s and still, at this moment […] This is a primitive world. Its practices, beliefs, religions, are uneducated, unenlightened, savage, destructive, already in the past […] That’s why Sun Ra returned only to say he left. Into the future. Into Space.”13Amiri Baraka, in Perspectives by Incongruity, ed. Benj DeMott (New York: Transaction Publishers, 2012), 224.

*

A Jimbo Easter Discography

by Bryce Schumacher

1997

- Jim Beam And The Throw Ups: The Last Matador & Already Dead songs were released on Bottom Of The Barrel. Compilation cassette on Good Records.

1999

- The Piranhas: Garbage Can. 7-Inch released on Tom Perkins Records.

2000

- The Piranhas: Piranhas Attack. 12-Inch EP released on Tom Perkins Records.

2001

- The Piranhas: Dictating Machine Service. 7-Inch released on Rocknroll Blitzkrieg.

2002

- The Piranhas: Erotic Grit Movies. Album released on both LP vinyl and CD on In The Red Recordings.

- The Piranhas. Compilation vinyl and CD both released on On/On Switch.

2004

- The Piranhas: Piscis Clangor. LP vinyl released on In The Red Recordings.

2005

- Odd Clouds: Liquid Moon Ritual EP. CD released on Casanova Temptations.

- Th' Hash Of Mystery. Cassette released on Fag Tapes.

- Untitled. Cassette released on Fag Tapes.

- Jamie Easter: The Will Of The Serpent Sundial. CD released on Tasty Soil.

2006

- Odd Clouds: The Cavernous End. LP vinyl released on Ypsilanti Records.

- Nightshade. Cassette released on Fag Tapes.

- Blood Jams. Cassette released on Fag Tapes.

- Jamie Easter: Insexual Innerds. Cassette released on Tapeworm Tapes.

2007

- Odd Clouds: Cleft Foot Of The Woods. CD album released on Tasty Soil.

- Split. Cassette (Wigwam is the artist for the B side) released on Arbor.

- Shamblers. Cassette released on Fag Tapes.

- Drona Parva: Drona Parva. CD album released on Fag Tapes.

- Alien Language Removal. Cassette released on Fag Tapes.

2008

- Odd Clouds: Untitled. LP Picture Disc released on Qbico.

- Slow Breath And Red’s Heartbeat. 7-Inch vinyl released on M’Lady’s Records.

- Druid Perfume: Life In The Bog. LP Album released on PIGS.

2009

- Odd Clouds: Deceiving Illusion. LP album released on Not Not Fun Records.

- Druid Perfume: Says Don’t Eat Em, They’re Poison. 7-Inch vinyl released on X! Records.

- Other Worlds. 7-Inch vinyl released on M’Lady’s Records.

- Goat Skin Glue. 7-Inch vinyl released on Italy Records.

2010

- Druid Perfume: Tin Boat To Tuna Town. LP album released on BUMBO.

- Druid Perfume: Third Album. LP vinyl released on Urinal Cake Records.

2013

- Moonhairy: The Kingdom Of Eternal Poverty. LP vinyl released on Urinal Cake Records.

- Paradise Hoax: Paradise Hoax. CD soundtrack self-released.

- Jimbo Easter & Chad Gilchrist: Owl Raga. Cassette released on UFO Factory.

- Odd Clouds: Cloud Odds. Cassette released on Fag Tapes.

2016

- Diamond Hens: Diamond Hens. LP vinyl self-released.

- Jimbo Easter: Jimbo Easter. 7-Inch vinyl released on Terror Trash.

References