People ask how might we “meet in the middle,” as though this represents a safe, neutral and civilized space. This American fetishization of the moral middle is a misguided and dangerous cultural impulse.

What is halfway between moral and immoral?

-Tayari Jones 1Tayari Jones, “There's Nothing Virtuous About Finding Common Ground,” Time (October 25, 2018). Accessed November 09, 2018. …

On July 23, 1967, Detroit police raided partygoers who were celebrating the return of two soldiers from the Vietnam War at the United Community League for Civic Action in the Virginia Park neighborhood of Detroit, Michigan. Tensions were already high from institutional racism, battling the Detroit police, housing discrimination, and lack of employment opportunities. But the police brutality, in particular, had worn on Black souls. The Big Four of the police force was created because the Black population was growing and they needed to be controlled. Their tight grip created a push-back that eventually resulted in forty-three people dying, over a thousand injured, and thousands of buildings destroyed during five hot summer nights.

When talking about the 1967 rebellion, no one discusses who won. Perhaps because the rebellion continues, it has never ended. I entitled this sound exhibition Pleasures of Rebellion to highlight the unnecessary need for civility in a time of absurdity and the satisfaction of actually acting on one’s beliefs. In Detroit, we are grappling with the same issues that prompted the rebellion in 1967. In fact, it was reported in 2017 on the 50th anniversary of the rebellion, that Black Americans remain challenged by the same socio-economic disparities that were present in 1967. That is an indication the rebellion was not successful. However, if you ask the children of the rebellion, those born after 1967 and before the mid-1980s, they may disagree. It can be argued that the rebellion created an imperfect utopia of Blackness that we still long for and fight for. The nostalgia of that era has even infected those who visit or are new to Detroit. They begin to join the fight for the imaginary utopia of long ago. There is a yearning to have that memory of Black bliss come alive, transform itself, grow and expand. But it won’t.

As Detroit faces water shut-offs instituted by the city government, an overwhelming poverty rate, school closings, and more, Detroiters yell at the top of their lungs for policies they desire, but the requests land on deaf ears. The legacy of continuous disrespect and harm instituted by city government only fosters frustration, resentment

and ultimately anger as it did in 1967. However, it was that particular rebellion that gave birth to the local hero Mayor Coleman A. Young, a former Tuskegee Airman and the first Black mayor of Detroit. Young was unafraid of facing the oppressive forces ruling Detroit at that time. Civility was not in his repertoire. Respectability politics did not exist for this man. There was no moral middle with Mayor Young, and should there have been? If people are being harassed, violated and killed because of the bodies they occupy, where is the civility in that? What is the moral middle within the prison of oppression?

When Mayor Young took office in 1974 the policing strategy called S.T.R.E.S.S. (Stop The Robberies Enjoy Safe Streets) was in place trying to continue the legacy of the Big Four, a police group which focused on targeting and brutalizing Black bodies. One of his first acts as mayor was to shut down S.T.R.E.S.S. and to reform the police department. I was born into the Detroit that Mayor Young built, thankfully. It was glorious. Imperfect and wondrous. A safe place for a little Black girl to establish a sense of self through the lens of being unapologetically Black. This was the case for most children of the rebellion.

We are moving deeper into the 21st century with the level of racial violence steadily increasing because the president, a self- declared nationalist, loves stoking the fires. The 1967 rebellion serves as a reminder of what happens when the fire is stoked for too long. It also beckons upon lessons learned from rebelling. History of the 1967 rebellion is expansive holding the memories of pain, pride, and collective vision. The rage from that summer carved a new direction for Detroit nd we are still feeling the aftershock.

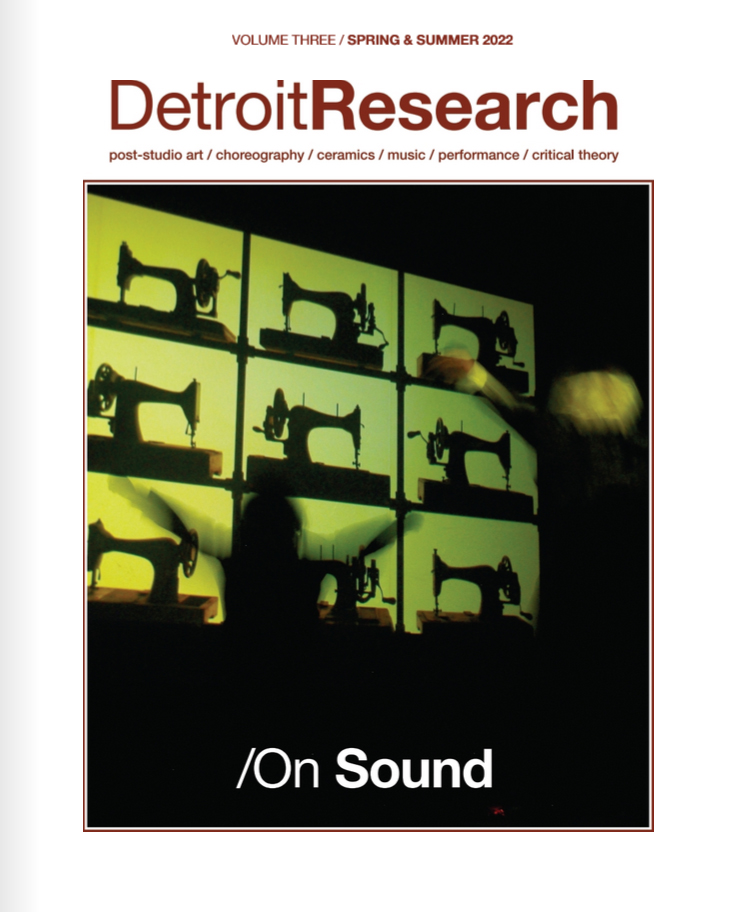

Sound artists Sadie Woods, Sterling Toles, and Reuben Telushkin build upon the consequential wave generated by the 1967 rebellion by taking us on an aural journey of the past, present, and future. It is within the imaginary that the sounds help us come to terms with what happened, what is happening now and what is to come. Each of their sound journeys uniquely prepares us to recognize that rebelling can be useful, messy, violent, but ultimately healing.

References